Last month, my family and I had the unique opportunity to travel to Kenya, Africa, for two weeks. My wife had professional reasons for being there, but I’ll admit that I went with the typical intentions of a Westerner—to see a world of new wildlife and experience Kenyan culture. I was richly rewarded on both of those accounts. Exotic wildlife is plentiful in the country’s many national parks. And, the Kenyans we met, both in cities and small villages, were warm, welcoming and very willing to share their lives with us.

Last month, my family and I had the unique opportunity to travel to Kenya, Africa, for two weeks. My wife had professional reasons for being there, but I’ll admit that I went with the typical intentions of a Westerner—to see a world of new wildlife and experience Kenyan culture. I was richly rewarded on both of those accounts. Exotic wildlife is plentiful in the country’s many national parks. And, the Kenyans we met, both in cities and small villages, were warm, welcoming and very willing to share their lives with us.

Still, the curiosities of a woodworker don’t take a back seat, just because a guy spends a couple weeks out of the shop.

Still, the curiosities of a woodworker don’t take a back seat, just because a guy spends a couple weeks out of the shop.

As I soon discovered, Kenyans from the Kamba Tribe, which make up about 11 percent of the population, are exceptional woodcarvers. When we started seeing examples of their work in kiosk stores along our trip, I had to learn more.

One of our safari guides, a thoughtful and patient fellow named Benedict Ndambuki, is Kamba—or more correctly, Mukamba. It was a stroke of luck for me. While Ben was somewhat embarrassed to admit that he doesn’t carve well (“That explains why I lead safari groups,” he confessed) he knows the carving tradition of his people first hand. His uncle and brother carve for a living. Ben explained that carving is an extension of Kamba spirituality. Mothers give life, but the form is shapeless. God, whom they call Ngai, imparts shape to all living things. Carving is the Kamba response to Ngai’s creative efforts. It’s a tradition carried on by Mukamba men, who are the traditional heads of households.

One of our safari guides, a thoughtful and patient fellow named Benedict Ndambuki, is Kamba—or more correctly, Mukamba. It was a stroke of luck for me. While Ben was somewhat embarrassed to admit that he doesn’t carve well (“That explains why I lead safari groups,” he confessed) he knows the carving tradition of his people first hand. His uncle and brother carve for a living. Ben explained that carving is an extension of Kamba spirituality. Mothers give life, but the form is shapeless. God, whom they call Ngai, imparts shape to all living things. Carving is the Kamba response to Ngai’s creative efforts. It’s a tradition carried on by Mukamba men, who are the traditional heads of households.

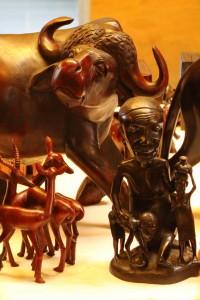

Kamba chip carving takes a variety of forms. Much of what we saw were African animals, probably encouraged as much by tourism as customary practice. But, there were also many examples of human subjects, bowls, bookends, wooden jewelry and ceremonial masks. I learned that most local woods are used for carving, with ebony and rosewood figuring prominently. I also saw teak and something the locals call white oak—which didn’t look like the white oak we have here in the States. Carvings took all sizes and shapes—some small enough to fit in a pocket on up to 8 or 10 feet tall. All were exceptionally detailed and, in my opinion, reasonably priced considering their fine craftsmanship.

Kamba chip carving takes a variety of forms. Much of what we saw were African animals, probably encouraged as much by tourism as customary practice. But, there were also many examples of human subjects, bowls, bookends, wooden jewelry and ceremonial masks. I learned that most local woods are used for carving, with ebony and rosewood figuring prominently. I also saw teak and something the locals call white oak—which didn’t look like the white oak we have here in the States. Carvings took all sizes and shapes—some small enough to fit in a pocket on up to 8 or 10 feet tall. All were exceptionally detailed and, in my opinion, reasonably priced considering their fine craftsmanship.

Near the conclusion of our trip, while en route to Lake Nakuru, we stopped at a large, roadside carving cooperative. There were literally thousands of carvings on display, created by local artisans. While I couldn’t quite learn how sustainably the wood is harvested, I was told that this particular shop purchases it “dead” from government sources. After bartering with the proprietor—an expectation of Kenyans in this situation—we bought a few more carvings to add to our souvenir collection. He invited me to visit the shop behind the store; one of two “shifts” of carvers were working that day. I was in luck again!

Near the conclusion of our trip, while en route to Lake Nakuru, we stopped at a large, roadside carving cooperative. There were literally thousands of carvings on display, created by local artisans. While I couldn’t quite learn how sustainably the wood is harvested, I was told that this particular shop purchases it “dead” from government sources. After bartering with the proprietor—an expectation of Kenyans in this situation—we bought a few more carvings to add to our souvenir collection. He invited me to visit the shop behind the store; one of two “shifts” of carvers were working that day. I was in luck again!

When we walked around back, here was the shop I saw. It couldn’t have had a footprint much larger than a sheet of plywood. Four carvers were quietly working inside, with a fifth younger man taking his post just outside the door. No electricity, no air conditioning, no noisy machinery. Actually, aside from that familiar sound of sandpaper on wood, there was no noise at all coming from inside. The tools they used included a few short-bladed chip carving knives, a variety of adzes in several sizes, rasps, files and sandpaper. They used their feet to steady workpieces on the dirt floor. There was no room for a workbench.

When we walked around back, here was the shop I saw. It couldn’t have had a footprint much larger than a sheet of plywood. Four carvers were quietly working inside, with a fifth younger man taking his post just outside the door. No electricity, no air conditioning, no noisy machinery. Actually, aside from that familiar sound of sandpaper on wood, there was no noise at all coming from inside. The tools they used included a few short-bladed chip carving knives, a variety of adzes in several sizes, rasps, files and sandpaper. They used their feet to steady workpieces on the dirt floor. There was no room for a workbench.

I was told that each man specializes in certain types of carving. The only carver who was introduced to me by name was Simon. He carves the ebony elephants shown here. Another artist was using a rasp to shape a thin teak statue of a man. A third carver was working on a stacked representation of Africa’s “Big Five” animals. The fourth was sanding…and sanding. Even in an Africa, someone is always stuck with sanding. Despite the obvious talents of these five carvers, I was told that even small carvings can take weeks to complete. I didn’t have the heart to inquire about how much each carver is paid for his efforts, but I was assured that the cooperative’s profits are directed back to the artists.

I was told that each man specializes in certain types of carving. The only carver who was introduced to me by name was Simon. He carves the ebony elephants shown here. Another artist was using a rasp to shape a thin teak statue of a man. A third carver was working on a stacked representation of Africa’s “Big Five” animals. The fourth was sanding…and sanding. Even in an Africa, someone is always stuck with sanding. Despite the obvious talents of these five carvers, I was told that even small carvings can take weeks to complete. I didn’t have the heart to inquire about how much each carver is paid for his efforts, but I was assured that the cooperative’s profits are directed back to the artists.

The completed carvings receive quick and simple finishes. Dark shoe polish to stain those pieces that need it, followed by a mixture of beeswax and what smelled like turpentine. The pieces dry in the sun before receiving a final buffing. Then they’re moved into the store for display. It’s a simple enterprise that continues day in and day out for these Mukamba carvers.

As you can imagine, I left their woodcarving shop with a mix of emotions and some impressions I won’t soon forget. The experience was both fascinating and inspiring, but at the same time humbling and bittersweet. One of Simon’s elephants now stands on a shelf near my computer to remind me of it.

Catch you in the shop,

Chris Marshall, Field Editor