The North Bennett Street School has a well-deserved reputation for both teaching woodworking excellence and for having a decidedly traditional slant. Both those qualities are instantly apparent in the work of William Thomas, a New Hampshire furniture maker and graduate of the school.

“I started building furniture when I was about 22,” William explained, “after first trying my hand as a potter. I initially hooked up with a couple of friends doing carpentry work. Although I had always been interested in furniture, I had no shop and no way of doing it. I heard about the North Bennett Street School, and enrolled in 1978.

“At the time, their furniture program was a sleepy little group that was barely hanging on by a thread and was threatened with being shut down by the fire department. They got some money to upgrade, hired a new director, and the school took off. That was about the time I started there. There was a one-year waiting list at the time. While I was waiting, an old woodworking shop came up for sale in Hillsboro and I bought it. The shop was full of history and old metal. In 1998, I bought a house in Rindge, New Hampshire and moved there. I always enjoyed working with wood, and I was glad to be able to get into it, and going to school gave me the confidence to do it.

“The philosophy at North Bennett Street is to teach 18th century American furniture making with the belief that learning the joinery from that period prepares you for building any kind of furniture. That period exemplifies complex joinery, high quality, sculpture, carving, inlay and sophisticated finishing. It was during the 18th century that this sort of work was perfected and advanced. Prior to that, furniture tended to be simpler. There is a lot going on in those pieces that provides great training.

“For example, Philadelphia Queen Anne and Chippendale chairs of that period did not have stretchers. That created a weakness that may partially explain why so few are left. Other cabinetmakers from the period saw that and modified the design. Thus, Sheraton and Hepplewhite, who came later, reintroduced stretchers in their designs.

“One thing I’ve done a lot of is wing chair frames. A few years after I got out of school, a couple of guys in Peterborough, an antique dealer and a commercial woodworker, formed a partnership and created a line of reproduction furniture. They approached me about creating a line of antique wing chairs. They borrowed an original antique, and I took measurements. I would make the frames as they got the orders. Even after that arrangement changed, I continued to keep them in my line.

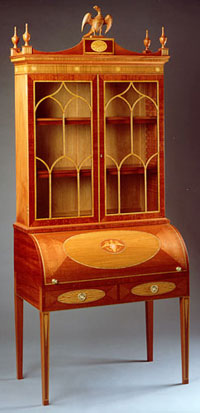

“Except for the wing chairs, just about everything I have built has been on commission. One of the pieces I consider the most beautiful is a cylinder fall secretary, a copy of a piece in Winterthur from the Federal period. I took a book of American period furniture with me when I visited the client. As we came to that page, she asked if I could build her that. I was floored because it had long been about my favorite piece of furniture. In fact, that page had thumbprint wear from the many times I had looked at it.”

While most of his work would fall firmly into the traditional category, there are exceptions. “About two years ago,” William recounted, “I had a dream about a piece of furniture. I woke up with an image of a small cabinet with a glass panel on the side. It was strange enough, and a strong enough image, that I went to the shop and sketched it. A few weeks later I bumped into a friend who does art glass, and told him about the dream. He created the glass, and I built the piece on spec for the New Hampshire Furniture Masters Association auction.

“New Hampshire Furniture Masters Association is a group of furniture makers who originally got together to pool marketing efforts. We hold an annual auction with a very unusual slant. We find clients, then build them pieces with the understanding that they will put them in the auction, and if they sell, we will build them replacements. It doesn’t always work out quite that way,” William admitted. “One maker’s client refused to let the piece be sold, so the maker had to create a duplicate for the auction.

“The auction also inspired a series of tilt-top tables. The first was commissioned by a customer for the auction. It ended up in a bidding war between [New Hampshire] Governor [John] Sununu and Senator Judd Gregg. Sununu got it. I then built a second one for the client who commissioned the first, and a third similar table, but with three legs, for another client.

“Another table ended up as a conference table in a bank. It is five feet in diameter and sports a bent laminated ring stretcher, a design that solves some of the instability of a pedestal table. A pair of mahogany and birch stump burl Portsmouth chests were made for a client who uses them as night tables. One piece that varies tradition slightly, a coffee table, is styled after a type of butler’s table, but features a sheaf of wheat as its inlay. Although the sheaf is a common carving motif, I had never seen it as an inlay.

“I think it is a shame that so much mass produced furniture is so poorly made,” William lamented. “There’s no reason furniture cannot be cost-effectively built well. I often suspect that planned obsolescence is the culprit as much as anything else. Personally, I like to build things of high quality, and not just because I have clients who can afford it.

“One of the interesting things I have found out while doing this is that when you are working for a client building commissioned furniture, the clients become your friends. You have a close personal relationship with them. By the time the piece goes into their home, we’ve gotten to know one another. That adds another dimension to the piece for both of us.

“One of the reasons people value antiques is that they perceive them to be handmade. They spend a lot of time researching the makers and history. But the difference between an antique piece made by the late John Goddard and one made by me, is that you can call and talk to me directly.”