Although Trent Davis “just kind of fell in love with building stuff” in his middle school shop class, what got him back into it as an adult “was actually making haunted houses for Halloween.”

His first offering was a maze created from plastic sheeting, but for the next year, “I was trying to go for realism. I wanted to make it absolutely feel like you were in a haunted house, so I made walls with wainscoting and a fireplace and all this stuff. It was, ‘Can I create the illusion of realism in darker light where I don’t have to worry about sloppy cuts or faux finishes or anything like that?’ I wouldn’t say it was fine woodworking, but it was pretty good woodworking.”

Although Trent’s moved on from those haunted houses – in part because the neighborhood kids grew up and grew out of them – his time creating them happened to coincide with the economic downturn. “A lot of the high-tech industry were laying off people, and I was in that boat. So I found myself newly looking for work and with a renewed interest in building stuff.”

He ended up, then, at the Oregon Museum of Science and Industry (OMSI) doing exhibit construction. “I remember saying to my wife when I got the job, ‘This is probably the closest I’m ever going to get to working for MythBusters. I was building exhibits both out of wood and metal and whatever strange materials we might be using, but I was also doing some electronics work, I was doing some programming.”

With backgrounds in woodworking, metalworking, electronics, music and more, one of the projects Trent is currently working on, on and off – “I’m like the king of unfinished projects” – is an apprehension engine, an experimental musical instrument created for music and sound effects in horror films, including the 2015 movie The Witch. “Just seeing their version made me go, ‘Yeah, I gotta do it,’” Trent said.

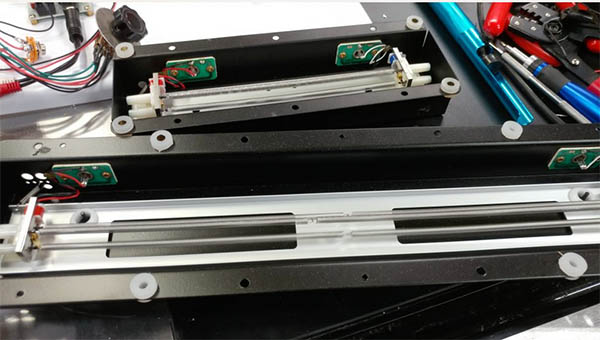

“It has typically a wooden box and then you can attach springs and pieces of metal; basically you’re making all these different instruments to attach to this piece, but then it’s also electric so you have pickups and a reverb tank and stuff like that inside there so it can go through a PA system and go through some more effects. So it’s more of, I wouldn’t say a musical instrument, as much as it is a sound machine.

In Trent’s version, he’s been doing some metal engraving for decoration — “These things tend to have a very specific look to them, kind of like Old World-y Victorian kind of creepy” – and it can also incorporate leather, either as a sound effect or part of the décor, plus, “obviously, woodworking and electronics as well. A project like this is something that really kind of pulls on all of the information you may have swirling around in the back of your mind about making instruments so you can incorporate techniques of guitar making, luthiery, or various percussion instruments, playing around with vibration and everything.”

Trent, a percussionist, does also make stave drums, which he sometimes uses himself in music recordings and often gives to beginning drummers. “I spin ‘em on a specially made jig that spins over a router table to [turn] the outside, and then I have another jig that uses a router to turn the inside as well.” He frequently sources wood for these projects from posts on Craigslist or Facebook Marketplace of old hardwood flooring.

“You get it in three-quarter-inch slats, typically, which are perfect, and it lets you play around and experiment with materials that may not be your first choice for making a musical instrument out of.” In general, Trent said, “Good and bad is just subjective.” For example, “A drum is just a big acoustic chamber. If you’re making something like that out of a hard wood, it’s going to reflect a lot of the sound. It’s going to sound a little bit more harsh, a little bit louder. Whereas, if you use a softer wood, it’s going to absorb some of that sound; it has a little bit of a mellower sound. If a certain wood really absorbs a lot of low frequency and makes something that should sound low just kind of sound dead, well, maybe I can use it for something else that would use a lot of the high frequencies.”

Or, he added, “I make some really nice-looking firewood sometimes.”

Trent’s favorite type of things to make are “things that I’m going to use. I’m not a big fan of going to the store and buying a pre-made jig for doing something. I’d rather make the jig myself so I can control all the different aspects of it.”

That preference for practicality is also reflected in the project he’s most proud of, a desk for his wife. “When I made that for her, the fact that she said it was great was one thing; the fact that she actually uses it every day, that just kind of helps confirm it.”

Such useful items are a contrast to his days in the high-tech sector: “You spend years working on something there and, when it’s done, it just exists in the ether. You can’t put your hands on it and a few months later, it’s obsolete and no one’s using it anymore. That gets frustrating.”

Helping others from that background get into creating tangible items through woodworking is a part of Trent’s day job – and his personal projects, too. In addition to working as a service technician at SawStop, he teaches local classes on taking care of your saw, “and I spend hours on the phone talking to people, both on the clock and just running across them in the store, like at Rockler or places like that.”

“The thing I really love is helping others accomplish what they want. It isn’t necessarily woodworking; it could be metalworking, it could be music, it could be whatever. When I can explain something to someone and they’re kind of looking a little bit lost and then you see it suddenly click and they’re like, ‘Oh, I get it now’ and then they go on and they’re able to accomplish what they want, I feel kind of like a proud parent whose son just scored the touchdown. I just stand back and go, ‘Yep, there we go. That’s what we’re talking about.’ And so, really, that’s my biggest passion.”