Years ago, Tom Schrunk was making things – in stained glass. This led him into woodworking when he couldn’t get the frames he wanted for his stained glass, and decided to make his own.

Then he had an offer from someone to buy his stained glass studio, which led Tom to keep the framing business and go into that full-time. However, “I had a summertime fall-off in business,” he said. “Stained glass is mainly hobbyists, and they were gardening and doing things outdoors, instead of staying in the basement where they were supposed to.”

Tom decided he would spend some more time with his son (aged five at the time) and the boat – except that he didn’t have a boat. So, he built a wooden one. Which someone bought. Then he built another, and so on, until he was building about one boat per year.

As he built these boats, Tom said, “I wanted to tweak people’s curiosity.” He was incorporating marquetry of full-size game fish, like muskies, northerns or small-mouth bass, onto the boats. “I usually put one fish on one side of the boat and one on the inside.”

Tom also played with the wooden protective strip on the gunnel of the boats: “I’d take a hack saw and make very shallow cuts, and glue pieces of veneer in every inch, to have a built-in ruler to measure the fish we caught.”

The boats were built mainly from mahogany, with stripes of avo dire veneer. Avo dire is “a very blond wood, very metallic, almost like gold,” Tom said, noting that he has only seen it as a veneer, never as lumber.

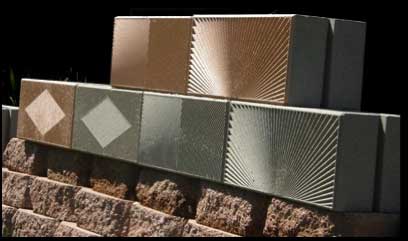

His experiences with avo dire, combined with an accidental bump against brushed brass, have contributed to what Tom’s work focuses on today: art in lustrous materials, including not only wood, but also brushed metals and concrete.

The brushed brass was in Tom’s possession because, again dating back to his stained glass days, he had an engraving business “because people sometimes wanted an engraved plate” on the frame of their stained glass. Tom accidentally bumped into a stack of brushed brass in his workshop, “and it fell over in a fan pattern, kind of like a deck of cards. The light coming off them was just amazing.”

How does this relate to avo dire? Well, Tom’s past also includes a stint as a Peace Corps worker in India, where, he remembered, Hindus would place small, square pieces of gold leaf on their religious statues. “They were 1 or 1-1/2-inch or so squares, and all those golden squares on statues stuck in my mind,” he said. “ I decided to make some square and emulate gold leafing.”

And, “Instead of the grain all going exactly in line with the sides, from one square to the next, I decided to change angles, just to see what it would look like.” When he completed this experiment, then looked at it from a different angle “Everything changed,” Tom said. “It was a eureka moment. I’ve been playing with that ever since.”

Some woods are particularly good for creating luster, Tom said, with mahogany and sapele among them. “Sycamore can be very, very interesting, and black walnut you can do marvelous things with. I’ve always been interested in how different woods respond to light. Some are just dead as a doornail. Some have an inner fire.”

Among the “dead as a doornail” woods, when it comes to luster, is gumwood – “the pigment carrying the color is totally opaque,” Tom said – with zebrawood and several rosewood species also less than lustrous. African rosewood, or etimoe, on the other hand, is not a member of the dalbergia species and is “brownish-orange, sort of stripey, and just wonderful, very lustrous,” Tom said. “Unfortunately, it’s also rather soft. A dining table would dent very easily.”

In his work with veneer, he notes, “there’s lots of cracks and fissures because of the way it’s manufactured. If it’s not a real durable wood, it can get pretty soft.”

Veneer is also “like a wood sponge,” Tom said. “To get the best optics with wood, you need a smooth surface, with multiple coats” of finish – varnish, in this case. “I use a lot more varnish than most people do,” he commented.

And that has led to his latest venture, the StopLossBag™. It’s a bag designed to preserve finish and help prevent oxidation and evaporation. Tom started developing them about 11 years ago, and offering them to the public this year. Without using the StopLoss Bags, it used to be, “year after year, I’d have to get rid of a good number of varnish cans with one half to one third of it skinned over,” Tom said.

Although he doesn’t know for sure how long finishes will last in the StopLossBags, Tom said that he himself currently has some varnish in bags that turned up on his workbench after being stored for over two years. The varnish is still viable.

He started a test in August, using a popular varnish, a salad bowl finish and a Danish oil finish, putting some of each in the original container, and some in a StopLossBag. By December, Tom said, the Danish oil finish in the original container was still good, but the others had skimmed over. “I’ve been weighing the StopLossBags on a weekly basis to see if evaporation is coming through the bag wall. It’s within half of a gram of where I started.”

Designed for oil-, water- and alcohol-based finishes, the bags are reusable. “One of the unsung benfits of the bag is, if you have a little touchup job, it’s so easy to open the bag and pour out half a cup or a teaspoon or whatever you need for touchup,” Tom said. “I use these things on a daily basis.” (Keeping with the kitchen utensils theme, he began transferring the finish from its original containers into the StopLossBags using a turkey baster. The bags’ filler tube now adapts to different sizes of funnels.)

“The bag stands by itself when filled, then you squeeze the bubbles out” (before tightening the cap), Tom said. Although he’s still selling through his stock of the original bags, which hold about 1.2 quarts, he has tweaked the design so that newer StopLossBags have an actual capacity a bit closer to 1.1 quarts, “just so they stand up a little straighter and look a little bit better,” Tom said. He also changed the corners from square to round: the square corners catch on the bubbles in the bubble wrap envelopes Tom uses for mailing.

Although Tom does already hold six patents (three on lustrous concrete, one on a glass texturing technique, one on a table for stained glass, and one for an aluminum extrusion), his patent attorney has told him the that the StopLossBags concept is too simple to patent.

That hasn’t stopped the attorney from wanting to work with him to get the bags suitable for other finishes, including oil-based or latex paints. (That’s still in the works.)

“The thing that’s got me by the chain right now are these bags, because they really work. You get more of the finish you paid for, and it cuts down on waste,” Tom said.