While working on tree trimming jobs as an arborist in the Twin Cities area of Minnesota, Tom Peter would notice things about the trees. “As I cut them, I would se the inner beauty,” he noted. “You can probably imagine cutting that tree and seeing that cross-section and going, ‘Oh my gosh, look at those colors!’”

So, after a friend taught him how to turn bowls, something that Tom found he had an innate talent for, he started turning some of the wood from those tree trimmings into natural edge bowls. And he found a connection between the bowls he was making, the trees they came from, and the people who loved those trees.

“My daughter coined my company a ‘heart-based company’ because that’s what this is: It’s really a labor of love, and I get paid for it, and it’s about connecting people with their trees.”

The start of Tom’s company, Respectful Transitions, came from an experience he had while still working full-time for a Minneapolis-area tree company. Since he had customer communications skills due to prior work experience in the insurance and telecommunications industries, the tree care company “would throw me out into the really tense situations.”

In this case, “There was a particularly tense situation on the chain of Minneapolis lakes. There was a request to remove a tree, and it happened to be a 70-year-old English yew, which in my mind should not have been taken down. However, the new homeowners, in what I call the ‘starter castle’ just wanted to wipe out the entire landscape. This particular tree was on the border between them and a house which was actually on the historic register. I show up on site and I know this isn’t going to be pretty. They wouldn’t send me to these things if there wasn’t something brewing.

“So, sure enough, I got there, and the neighbor lady said, ‘You are not taking down that tree!’ and I said, ‘You know, you’re right. I love this tree! What’s the deal?’ And she told me this wonderful story about how her daughter used to climb to the top of the tree, which was across from the second story window, because mom was a seamstress and she needed to do her work, so her daughter would take her teddy bear up the tree and talk to mom because now she’s in the window and mom can see daughter and daughter can see mom. She was expressing the emotional challenge that her daughter would have by coming home that winter and seeing the tree be gone.

“Anyway, through this conversation, getting all of her emotions out, she was then able to let go of the tree and say, ‘You better take that tree down.’ And it was kind of funny because I was arguing with her and I said, ‘You know, this is a beautiful tree and it really shouldn’t be taken down.’ And she said, ‘Well, what’ll happen if you don’t?’ And I go, ‘Ah, somebody else’ll do it. You know, there’s a lot of arborists in the world.’ So I took the tree down and, in so doing, I instructed the grounds crew and the people who were going to stuff this tree into a chipper to save most of it.”

The conversation and tree removal took place in August. By October, Tom had used some of the wood from the tree to make a piece for the woman, and brought it back to her. “I knocked on the door and offered this piece to the homeowner. I kind of had to fill in the gaps of the story for her because she was quite elderly, and by the time she reconnected with it all, she told me, ‘I can’t take this piece. I don’t have any money to pay you.’ And I said, ‘You’re right. You can’t pay me; this is priceless. Remember, it’s for your daughter.’ And she goes, ‘Well, I’ll take it on one condition,’ and I said, ‘What’s that?’ and she said, ‘You make me another one and let me pay you for it.’

“And that was the hatch of Respectful Transitions: somebody in this sweet spot of having an emotional connection to a tree and then wanting to pay me for something I’d make out of it.”

As a certified arborist, Tom can take down small to medium sized trees himself, but he says about 50 percent of the people he works with have a tree that has already come down, due to storm damage or previous removal for other reasons.

These days, he does have more and more people asking him to make something out of their ash trees. (As an arborist, Tom was actually involved in the early days of data collection regarding the emerald ash borer in Minneapolis: some of the earliest identified emerald ash borer larvae in the area are preserved in bottles with the annotation “harvested by Tom Peter.”) But he works with a wide variety of species, including, as a result of spending his winters in Arizona, things like olive wood and mesquite.

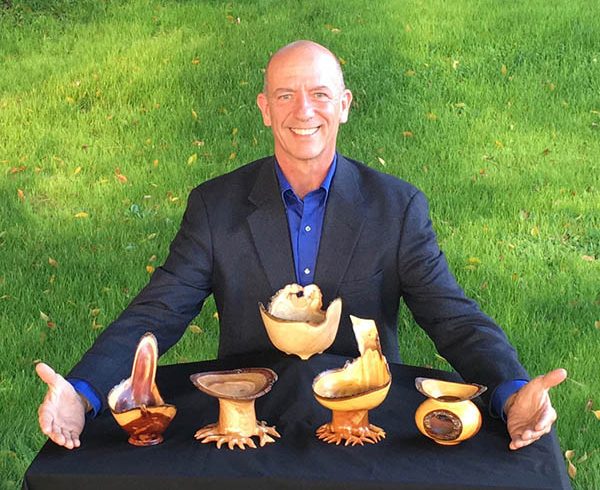

When working with species more typically found in his spring/summer/fall home of Minnesota, Tom said, “I love walnut because I’m one of the few artists who keeps the bark on the tree. The bark makes the difference because it creates a color separation between the beautiful heartwood and sapwood layers. So, the middle of the tree is the heartwood, the darker shade; and then there’s the sapwood, the outer, lighter ring, in most cases; and then there’s the bark. With walnut, it’s like three shades of chocolate: you’ve got your dark chocolate in the middle, then you’ve got your white chocolate, if you will, and then you’ve got your milk chocolate of the bark.”

Each of Tom’s pieces starts with a unique feature of the wood. “That’s where I start the turning process. I see a feature that I’ve never seen in any of the trees that I’ve worked with before. I cut that with my chainsaw, then I bring it into my shop and I cut it on the band saw. I do a circular form of that one area that I’ve never seen before and when I put it on the lathe and start turning it around and peeling away the layers, when that happens it literally has never been seen by anyone before.

“When I find a feature like a previously pruned branch or an undulation or a branch coming right through the edge, and I happen to capture that, that then becomes the feature and I create the rest of the vessel around that feature.”

Tom’s background and skills make him uniquely suited to work with such features, he said. “Here’s where my artist meets the arborist: By understanding the biology of what’s going on in the tree, I can anticipate magic in these places that are disposed to creating magic inside a tree that has been biologically altered by pruning, or by a storm, or by a bug.”

Those insights also help him as he teaches and demonstrates to woodturners’ clubs, at sites like Rockler stores and, most recently, at the Forces of Nature show at the Los Angeles County Arboretum. “It’s the biology of the tree which will dictate the outcome on the lathe in some cases,” he said, so he will incorporate into his demonstrations discussions of the physics and tree biology behind “the point where things can go wrong.”

Awareness of such things can lead to better safety, Tom said – even though one of his “calling cards” is a technique that seems to be particularly dangerous. “I draw a branch through the edge of a vessel,” he explained. “Why I bring it up is, it’s such a dangerous operation that it should never be done, because you have this protrusion spinning around at such rapid speed that it becomes invisible. It’s called a ‘ghost image.’ In my demonstrations, I absolutely exhort no one to try this at home because it’s so dangerous.

“From there, I say, ‘However, if you do exactly what I tell you from here on out, you should be able to do this without a problem. My three elements for turning are: safety, comfort and creativity, in that order, specifically. Only by understanding the physics and the mechanics of what could go wrong” can someone safely approach a project using their creativity, Tom said.

He does, however, note that he’s attempting to teach people around the country to duplicate his efforts, so that he can offer referrals and manage his own workload. “When I get an order for 100 pieces, there’s no way for me to do 100 pieces,” he said. His goal is to have connections with tree care specialists and woodturners in various areas who can make special somethings out of downed trees in their local areas.

“I’ll just connect the dots like that. However, I do have some people who say, ‘I want the Michelangelo, I want the master; price isn’t an issue because this is my most special tree.”

One example comes from another of Tom’s stories. “A gentleman called me up. A little bit of background story was, 20 years ago, he and his wife, when they got married, they planted a hawthorn tree. Ten years into their home and their marriage, the hawthorn tree died. They had to cut it down. He kept a piece – and, to my knowledge, I don’t think he told his wife about it. But it was a very special tree nonetheless.

“Ten years after, which is coming up on their 20th anniversary, he calls me and asks if I can make something for him. I usually didn’t work with wood that’s been dead for 10 years, but I said, ‘What a heartfelt story for you to give something to your sweetheart on your 20th anniversary from this wonderful tree. We got together and I said, ‘Well, when would you like this?’ and he said, ‘Well, today is Monday, and our anniversary is Friday,’ and so I said yes to that.

“I got the wood on Monday; on Thursday, I delivered it. And here’s what he did: He held this vessel – it was more the shape of a scoop or a tray – in his left hand, and in his right hand, he went into his pocket and pulled out a little velvet pouch, and he opened it with his teeth, and then he poured 20 red crystal hearts onto the vessel, and said, ‘This is what I’m giving my wife tonight.’”

As Tom said, “I have stories replete of the emotional effects these have on people.”