Some woodworkers spend an inordinate amount of time picking out just the right wood boards for their next project. Not so Steven J. Backman. His constructions are all made with the same basic materials: toothpicks and glue. Yes, toothpicks. Now, before you decide “Hey, this is not really woodworking,” stop and think about what he does and what you do.

Like most woodworkers, Steven starts with boards cut from trees, then combines and reshapes them, using glue and joinery to put them together into a different and more interesting form. The only real difference is the size of the “boards” at the outset.

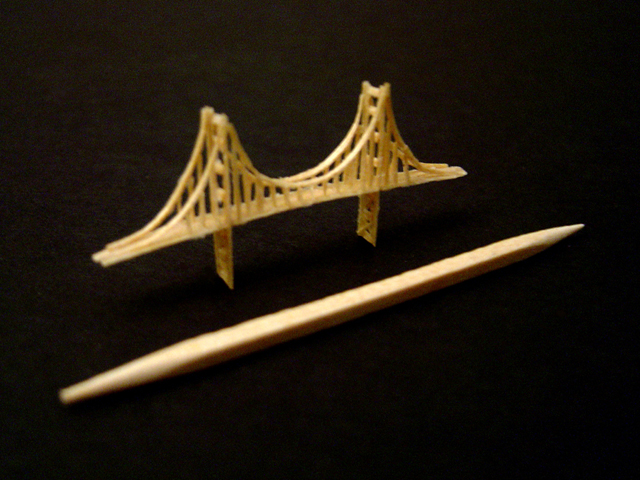

As for the size of the finished pieces, they can be surprisingly diverse, even when they are models of the same item. Take, for example, two models he made of the Golden Gate Bridge, one very large and the other impossibly small.

“The large one is 13 feet long, four inches wide and 16-and-a-half inches high,” Steven told me, “and took two and a half years to build. It contains some 30,000 toothpicks.The miniature version of the same bridge, pictured here with a single toothpick below it for reference, is under two inches long, took eight hours to build, and is made from just one toothpick.

“I built the large bridge in 1987, and it is the piece that made me famous. It now resides in Ripley’s Believe it or Not Museum and has been there since 1992. The construction mimics the real bridge design, right down to stress relief elements that permit movement typical of what would occur during an earthquake. The bridge is illuminated with over 100 light emitting diodes powered by one nine-volt battery.

“I built the little one just a couple of months ago after my father suggested I make something that will get me in the Guinness Book of World Records. I cut a toothpick into tiny slivers, bent the wood to make the main cables, and used tweezers to set the vertical cables.” In case you were wondering, it did not get him into the book; at least not yet.

While there are certainly other adults, and legions of children, who create with toothpicks, his precise and elaborate structures have gained him a notable measure of fame. His art has been showcased on a number of television programs and in innumerable magazine and newspaper articles. Perhaps even more surprising is that it is his day job. Steven admits that he suspects he may be the only person in the world making a full-time living making and selling toothpick art.

Of course, it started as a hobby. In fact, his first introduction to toothpick structures came just when you would expect: in grade school. “When I was about six,” Steven recounted, “I made a toothpick house. Then, in second grade, I made a model of a DNA molecule out of toothpicks and beans. While working on it at home, I got frustrated, hit it, and ended up with a toothpick stuck deep in my hand. That put me off toothpicks for a while. Later, while attending San Francisco State University in 1985, I made a large toothpick model of a cable car in lieu of a written exam on the history of San Francisco.

“After graduating with a degree in industrial arts and product design development, I worked a number of jobs both in and out of my field. Toothpicks, meanwhile, became an enduring hobby that quickly morphed into a business. For many years, I made and sold all different sizes of cable cars to collectors. All told, I probably made dozens of them. Some had lights and some were music boxes that played ‘I Left My Heart in San Francisco.’ Though I sold these, it was not yet a full-time job.

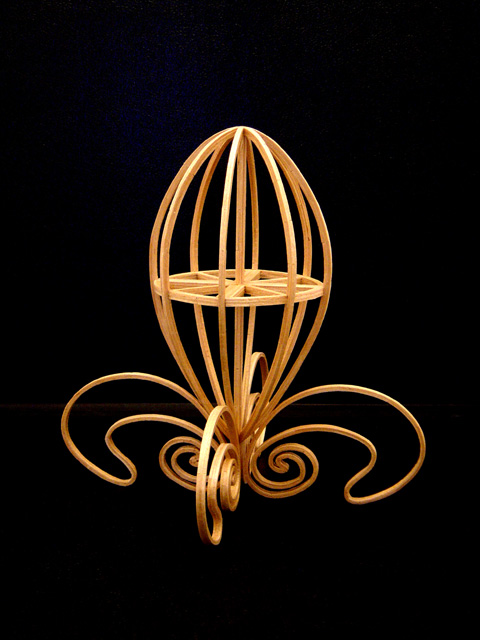

“Late in 2003, I saw an artist demonstration program at a museum, and the director of public programs suggested I expand my range and try some freeform sculptures. I made some very whimsical sculptures which were very well received, and images of them ended up being published all over. Several galleries started showing my work. I quit my job and became a full-time toothpick sculptor.

“My sculptures range from miniatures, which are just a couple inches high and are made in just a couple of hours using from nine to 20 toothpicks, to large complex sculptures that take hundreds of hours and thousands of toothpicks. Models of existing structures can get both fairly large and very complex. A model I made of the Empire State Building is 28-and-a-half inches tall and is formed from 7,470 toothpicks. I also submitted a proposal for a Freedom Tower to replace the World Trade Center towers in the form of a toothpick model.

“My favorite piece, though, and my pride and joy, is a working, floating radio controlled yacht made entirely of toothpicks. To ramp up, I first made a four-foot radio-controlled sampan, which worked and floated, then decided to dive into the yacht. Before I began, I talked to some boat builders to get some advice about engineering the boat.

“The yacht took six months, working ten hours a day, and is made from 10,000 toothpicks. Even the rudders are made of toothpicks. The top hatch slides open to allow access to the battery compartment. It sports an electronic speed control, a dual prop system, and has a water lubrication system for the moving parts. While the outside skin, which is sealed with polyester resin, looks like a simple layer of toothpicks, the inside is built with the same interior structure as a real boat.”

This is not to say that Steven never did more traditional woodworking. “In junior high woodshop I made a mahogany chest,” he told me, “using more normal woodworking tools and methods. When I was still a child, a friend and I made a multi-level treehouse made completely out of recycled wood and objects, including roofing materials and windows. The problem for me with more traditional woodworking is that although I could create shapes, they lacked the texture I get with my toothpick art. Toothpicks have a different personality.

“Many of my pieces are made not from typical toothpicks, but from toothpick blanks, which are the pieces before the pointed ends are shaped. In essence, I am working with miniature timbers. The pieces are two-and-a-half inches long and are square end to end. I get them from a large toothpick manufacturer. For glue, I use Elmer’s Glue All.

“The best toothpicks to build with are white birch. Sadly, many toothpicks these days are manufactured overseas of other woods, some of which are too brittle to work. Fortunately, I have a supply that should last me another decade. I’m currently looking for another company still making toothpicks the old way here in the U.S. out of birch, but so far, have not found one.”

These days about half Steven’s work is commissioned by collectors and companies, and the rest he sells directly from his web site. Prices on his page of available pieces range from eight dollars for a signed toothpick, to $25,000 for the one-of-a-kind Empire State Building.

Beyond the pleasure of building, and the day-to-day income, Steven gets a lot of satisfaction from the notoriety his unusual approach to woodworking has garnered. “I archive all the letters that I have gotten from all over the world about my work,” he admitted, “and now have some 39 binders full. My web site averages half a million hits per month. There are even four letters from President Bush, who owns one of my sculptures.

“I’ve made a lot of sacrifices for my art,” Steven conceded, “but I love what I do, and it means more to me than making a lot of money. Frankly, I never dreamed my grammar school hobby would become my day job and would take me so far.”