Back in 1797, just 20 years after America declared its independence from Britain, John Chapman started planting orchards of apple trees on tracts of land he owned throughout Ohio and Indiana. This earned him the sobriquet “Johnny Appleseed.”

In 1991, Steve and Sherry Brunner starting planting teak, nargusta and suradan trees, along with a few other species, on tracts of land they own in Costa Rica. So far, they have planted some two million trees and show no signs of slowing down.

Chapman’s goal was to provide pioneer settlers with apples, but Steve and Sherry set out to grow wood, and lots of it. “Once we saw those little trees coming up,” Steve said, “Sherry and I decided to devote the rest of our lives to doing this.” They created Tropical American Tree Farms, and estimate that just the trees they currently have under cultivation may eventually yield some 200 million board feet of wood. Extrapolating from current prices, that works out to two billion dollars worth of wood.

Perhaps best of all, they welcome anyone else who shares their vision to invest and become a partner in this unusual and earth-friendly venture. Obviously, there is more to this story than meets the eye, so I spoke with Steve to learn a bit of history and get a peek into the future.

“I graduated from law school in 1969,” Steve recounted, “and went into the real estate business. In 1974, I wanted to buy some warm weather oceanfront property for investment purposes, but land was too expensive in the U.S. Instead, Sherry and I bought 2,500 acres in four segments in Costa Rica, a country with a thriving economy, a long-standing stable democracy, and constitutional protection of private land ownership. I managed the property, flying back and forth between Costa Rica and Columbus, Ohio.

“Flying during the dry season, I would often see smoke rising. Farmers were cutting down the trees as fast as they could and burning them to get them out of the way. Their goal was to create cattle grazing land to feed the American beef market. You could literally see the rain forest disappearing, and it really bothered me. This was also causing the price of lumber to keep rising in the area.

“During the 1980s, I did a lot of investigating into wood prices and the feasibility of tree farming in the tropics. In 1991, Sherry and I decided to buy an inland farm to start a tree farm for ourselves. Our intention was to plant trees and harvest them 25 years later, but along the way we learned that we might not have to wait that long. There are some very fast-growing trees in that region.

“Some of the fastest growing tees that yield attractive workable wood are teak; gmelina, sometimes called white teak though it is not related to it; mangium, an accacia species; nargusta, a yellowish wood with pink stripes; and suradan, a dusty rose color wood that gets darker as the tree ages.

“Initially, we started buying land to prevent it from being deforested as well as land that had already been clear cut. We used the already cleared land for planting. We have never cut down any forest or any trees in the forest. Instead, we protect existing forest, and plant for production on other land. It should be clear, though, that what we create are tree plantations, not forests.

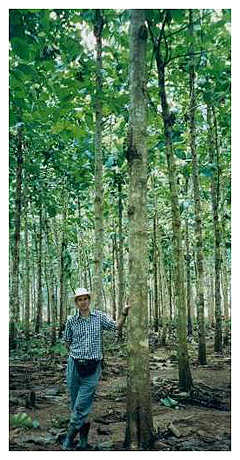

“Using local labor, we planted about 63,000 teak, nargusta and suradan trees, along with several other species, on about 150 acres. After the trees are planted, it is a non-stop process of weeding, and eventually pruning and thinning. The plantations all need to be thinned at various stages. Thinning starts after about seven years for some of the faster growing species, and for most species is done every three to four years after that. During thinning we take out the least desirable trees.

“Meanwhile, my wife’s father, who had been following our progress, asked to invest in the venture. We came up with the idea of selling live trees to others for investment purposes. The idea was that we would take care of them, but the trees would be owned by investors. When the woodworking community found out, we started getting invitations to speak to woodworking clubs.

“It’s grown from there, and today we have over two million trees under cultivation. We currently grow 14 different species for tree owners and 51 species for ourselves. More than half of the trees are owned by tree owners. Some do it for investment reasons, others for the wood, and a few are using it as an excuse to write off fishing trips to Costa Rica. We sell in multiples of 100 trees at about 50 dollars per tree. Each person owns specific trees with locations laid out by row and column.

“There is a risk, of course,” Steve was quick to point out. “Your trees could die while the ones nearby owned by someone else thrive. In 1996, for example, a hurricane came through, and we lost about 40,000 trees, all owned by tree owners. However, rather than let them take the hit, we replaced them with our own trees of about the same age. That way, no investor lost any trees. It’s not in our contract, but if truth be known, we would do the same thing again as long as we can afford it.

“When it was time for the first thinning, we already had some tree owners besides ourselves. We went in naively thinking the small dimension wood from the thinning would be saleable, but were disappointed to find it had little or no value. Rather than throw the wood away, we set up a workshop to find out what we could do with it. The first thinning was teak, yielding boards four inches and under. To our surprise, we discovered that young teak is even more beautiful than older teak, showing even more chatoyance and depth. We decided to use the wood to make really high-end furniture and veneer. With that, a second company, which we named Raleo®, was born.

“Raleo is a Spanish word meaning ‘a thinning’ and ,true to its name, the wood for Raleo furniture and wall treatments comes from the wood harvested during the thinning process. We made a lot of samples of various surfaces on small pieces of wood and took them to an upscale builder’s show. The response was overwhelming.

“We moved to a 10,000 square foot shop in San Jose, Costa Rica, hired some people, and started selling processed finished wood surfaces and furniture at high prices to upscale markets. We still sell strictly to designers and architects. In time, the facility has grown to 40,000 square feet, and the current demand outstrips what we can produce.

“To put it simply, Raleo, which Sherry and I own outright, creates value for underappreciated wood taken from early thinnings, then buys this otherwise low value wood from the tree owners. We pay a higher than market rate for the wood, often two and half to five times the going rate. The upshot is that it makes earlier monetary returns likely for tree owners.

“Of course, the bulk of the value for tree owners is still in the final harvest, which will far surpass whatever they glean from thinnings. The end goal is to produce not just sawn wood, but veneer quality logs, which have far more value per tree. We have been able to get veneer from trees as young as seven years old. It makes the prospects for this venture much better than it looks at first blush.

“Some of our tree owners have already gotten more back than what they paid for their trees just from the rewards of the first thinning, and they still have all their best trees growing larger. On the other hand, some are still waiting. We do not take any money from new investors to pay older investors. What you get depends entirely on what happens with your trees, and in part, how patient you are, since waiting longer usually yields a better pay out.”

Though investors are increasing, it is not due to active selling. “We try to graciously answer questions,” Steve admitted, “but that is it. If you are interested in finding out more, we invite you to browse the web site. There’s enough information there to help you decide whether this is for you.”

It must be right for a lot of people. At present, they have some 300 employees, thousands of tree owners, and own one tenth of one percent of all the land in Costa Rica. “Profit and love for the environment can go hand in hand,” Steve insists. “You can run a profitable business that also helps the environment and takes very good care of the land.” To guarantee that the company continues long after he and Sherry are no longer in the picture, they set up a trust that will continue to run it according to their values and the responsibility they feel to their tree owners.

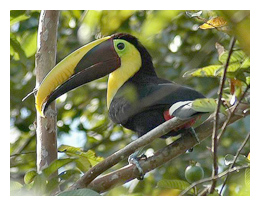

“We really believe that being good stewards of both trees and people is our mission in life. We don’t use herbicides or pesticides, and we don’t allow hunting in the farms. As a result, a lot of animal species that are considered scarce are returning, and these rarely seen animals will often come right up to the door. Some, like kinkajou and coatimundi, come right into our farmhouse.”

Lush surroundings, a good business and the satisfaction that you are doing right for both customers and the environment seems like a perfect combination, but there is still one more vicarious joy Steve admits to feeling.

“More than a thousand tree owners have been down here to see their trees and go through the rain forest,” Steve told me. “Seeing the rain forest for the first time is a hard-to-describe experience. Watching their reaction is almost as good.”