Steve Fitzberger’s Abba Woodworks company in Baltimore touts itself as not only working with reclaimed wood, but also working to reclaim lives.

Steve and his wife Diane, while also both working additional full-time jobs, started Abba Woodworks –- run out of a small shop in their basement –- a few years ago and began selling their wares at Baltimore area farmers’ markets. “We noticed that there were a lot of guy who were unemployed and homeless, and so we used them to helps us pack and unpack our trucks.”

Those first interactions grew into a setup in which Abba Woodworks becomes a training ground for some of the members of Baltimore’s homeless community. “We do everything from teaching somebody how to read a tape measure, or we’ll teach them how to read blueprints,” Steve said. “Sometimes, as soon as they learn how to read a tape measure, two weeks later, they’re gone and they’re working for someone else – which is fine. That’s part of the reason why I’m doing this, is to get people working and helping them to become successful in whatever endeavor they want to do.”

One of the things that helps him in this endeavor is access to free or low-cost wood: skids and pallets donated by businesses such as area restaurants and coffee shops. Steve cited one story in which an Abba Woodworks trainee made a box the wrong size and became greatly upset, thinking that redoing it would greatly increase the cost of the product. “I said, ‘No, it’s not an issue. You’re learning. If you make a mistake like this, you’ll learn from it and you’ll remember, OK this is what I need to do to make sure it’s cut correct the next time.’”

Steve got started using pallet lumber when a friend of his who works as a permaculturalist in Baltimore city schools and wanted to teach the students about gardening. “He said, ‘I have no wood, but could you make me some raised beds?’” The next day, Steve said, “I went to work and my boss came to me and said, ‘I have these skids and I don’t know what to do with them. I don’t want to throw them away, because they’re good material, but I don’t have any use for them.’” Steve took a few home, took them apart, and then made three, three-foot by 12-foot raised garden beds to donate to his friend’s school.

The raised garden beds have continued to be a popular product, with Steve and Abba Woodworks creating both stock and custom sizes that are used by Baltimore residents with poor soil for growing herbs or vegetables, or by schools or other organizations.

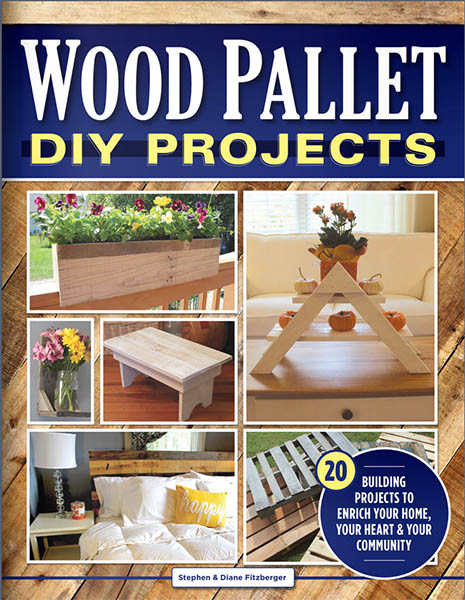

Among other Abba Woodworks products are wine racks, coat racks, tables, benches and serving trays – all original designs (Steve says some of them come to him in dreams) and all featured in Steve and Diane’s book, Wood Pallet DIY Projects from Fox Chapel Publishing [ISBN 978-1-56523-930-2].

The book also includes information on working with pallet wood, for which one of the main challenges, Steve said, is removing the nails. Generally, he said, there are two types of nails found in pallets: twisted nails or ringed nails (often used in flooring). He generally cuts off the ringed nails with an orbital saw fitted with a metal blade, while the twisted nails can be pulled out.

“That part of it is very labor-intensive, but when you have a guy who doesn’t have any skills, or very little skills, you just start him out with taking pallets apart,” Steve said. “What he learns from that is how to work with the wood: you have to be able to read the grain and you have to be able to run with the grain instead of against it.” If someone just starts prying a pallet apart, it will often break up and became useless for anything but firewood, Steve said, “but what they do is they learn there’s a certain technique in the way that you do it. You get more yield out of it if you go with the grain instead of against the grain.”

His employees, he said, are hard workers. Some might have learning disabilities or other issues in their backgrounds, such as a survival mode mentality from living on the streets. With one employee, Steve said, “I had to sit him down and say, ‘You’re in a safe place.’ I had to teach him that [the shop] was an environment that was healthy and good for him.”

Steve, who has dyslexia, can empathize. “I struggled in school, but the one place I didn’t struggle was in the shop,” he said. He credits his initial interest in woodworking to his grandfather, who “gave me a hammer and nails and a block of wood and just had me start nailing this block.” In part, the name “Abba” Woodworks, with “abba” meaning “father” is a way to honor his grandfather. “The other part is Abba is God our Father,” and the name is meant to honor “all of the things I feel like God has created and given us a creative outlet through Abba Woodworks.”

With 38 years of professional experience in woodworking, Steve said, “Woodworking is my background. It’s what I know. If I can teach somebody through that and then they can go and learn what they can get from me and then use the job skills and other things to get them into where they really want to be – I don’t know how to explain that.”