“This is like my little retirement hobby,” says Stan Saperstein of his carved walking sticks and canes. It’s a hobby that, in part, grew out of another of his hobbies: historic reenactment. Stan is a reenactor (also known as a living historian) of the American Revolution and Civil War. This hobby does involve staging battles from these conflicts, but it also entails spending time as a living historian of a soldier from the era in a mock military encampment.

“In camp, you’re supposed to do things the soldiers did in camp” in the appropriate time period, Stan said. For the Civil War in particular, he added, “One of the big hobbies was whittling, making walking sticks.”

Stan learned to whittle as a boy growing up in upstate New York. His grandfather had a truck farm near Albany, and Stan “spent every summer on the farm until I was about 17 years old. I got a pocketknife at six years old.” Although the main function of the knife was to cut baling twine from hay bales in order to feed cattle, Stan’s grandfather also ran a gas station in front of the farm which was the local gathering place for the neighborhood’s elderly men. “The old guys were always whittling, things like a ball in a cage, or a wooden chain,” Stan said, and he learned from them.

He also, as an adult, learned from his adopted grandfather, Clarence “Larry” Grinnell, a member of the woodworking family who were among the first settlers of Rhode Island and practiced woodworking in that state and the New York area from the 17th century onward. Stan served an apprenticeship under Larry Grinnell and learned 18th century woodworking techniques that he put into practice in his Artisans of the Valley woodworking business, begun as a side job while he worked for the state of New Jersey in the 1970s. Artisans of the Valley, now run by Stan’s son, Eric, focuses on furniture restoration and reproduction, as well as original designs and carvings.

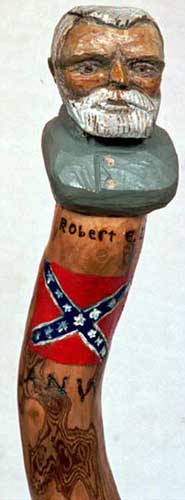

Reproductions have also figured into his walking stick business, as other reenactors, seeing him whittling in camp, asked Stan to make them “regimental walking sticks,” which had the regiment’s name and the battles that regiment had fought in carved upon them. For example, if someone requested a regimental walking stick from the 7th Virginia, “I would look up what the flag looked like, what battles they fought in, and put the appropriate information on the cane,” Stan said.

His pieces are not, however, limited to these military reproductions. After his son Eric put up a website featuring Stan’s work, orders began coming in from all over the country for walking sticks and canes – some from reenactors elsewhere, especially Southerners requesting historic figures like Robert E. Lee, but others from places like colleges which wanted their mascots featured on a walking stick.

Plus, he’s made canes from people around the world: a Scottish doctor who wanted a caduceus, a cobra for a fantasy role-playing gamer in Korea, and several with religious motifs for a client in California. The most recent one in this series depicts scenes from Exodus 25, in which God gives the Israelites instructions for building a tabernacle from acacia wood. “The acacia in the Bible is umbrella acacia because it has an umbrella canopy. It’s a small tree, the size of an apple tree, which in Israel today is highly protected. The wood comes up for sale maybe once in a generation,” Stan said.

He happened to be browsing a wood seller’s website and spotted an ad for Biblical acacia wood – $12 a piece pen blanks – and called his California client to tell him about it. “I didn’t really think he’d do it, I just wanted to get him excited,” Stan said. “Fifteen minutes later, he called back and said ‘the shipment’s on its way.'” Stan glued up 32 pen blanks of acacia – which he described as “a gorgeous wood, from a dark, reddish brown center, to an almost black stripe to white” – in a manner that emphasized the colors to make the cane.

When making canes and walking sticks, Stan said, if he is making a figurative head, it will be carved by hand, using a whittling knife or old carbon steel knives – or, for very hard wood, professional pulls. Sometimes, people will send old gold, silver or ebony cane heads, missing the shaft, for Stan to create a restoration piece. “I don’t turn them; I’m faster with a spokeshave and a tabletop sander,” he said. “I round it all over, so it’s almost perfect – not quite. Enough to tell it’s handmade.” Also, he noted, “Wood doesn’t dry round over the years, it dries oblong, so you don’t want it to be perfectly round to simulate old.”

He also utilizes some special techniques on certain pieces, such as the cobra, which was made from a naturally twisted piece of honeysuckle. Using a machine called a feather etcher, often used in making painted wooden decoys, “I put in every scale on that cobra,” Stan said.

Stan also needs to use techniques specific to the wood when he works with diamond willow, which is highly sought after by cane shaft collectors. Like spalted maple, diamond willow is not a species in itself, but the result of a fungus which grows on certain species of red willow and creates diamond patterns in the wood. “You have to carefully remove the bark and expose the diamonds,” Stan said. For concave diamonds, this entails taking the thin, silver bark out without cutting too deep and exposing the wood’s interior cream color, while for the raised, convex, diamonds, the bark is cut away around it so the diamond stands out. When making a walking stick rather than a cane, though, you must leave the diamonds unraised at the point where a hand would grip to avoid discomfort.

Diamond willow is one of his favorite woods to work with, Stan said – including a cane with a “Yoda” head” he made for a client who requested it because he claimed to look just like the Star Wars character – but he’s also worked with wenge, padauk, and purpleheart in cane making – although the predominant wood for restoration canes is Gabon ebony.

One form of reproduction cane he doesn’t get asked to make very often is the “gadget cane,” although he has made one – a sword cane – for his own use when playing Francis Hopkinson, one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence, as a living historian. (Stan also fixes cannons for the park service and teaches senior adult education courses at Princeton). Gadget canes stored a variety of items which were retrieved when a side button was pushed and the candle pulled out – including swords, shot glasses and small flags for the Fourth of July.

Stan considers his cane and walking stick making a way to carry on a folk art that was particularly prevalent in the U.S. Between the Civil War era and the 1930s, when it was often “hobo art”: walking sticks that were carved by itinerant hoboes in exchange for a free meal or a place to sleep. Also, he said, “It keeps me from mouldering away here in retirement.”