Have you ever felt like throwing your box joint jig out the window when, after a long shop session, the pins and slots still don’t quite fit together?

I suspect Alan Schaffter has. He’s had box joints “on the brain” for years and, more specifically, the difficulty in making them successfully with typical jigs and methods. For this retired Navy commander and mechanical engineer, most shop-made and commercial box joint jigs are far from shipshape. They’re probably better off lying in the yard.

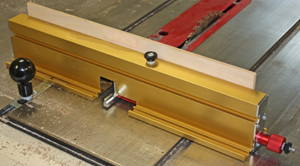

Schaffter found limitations with both template-based and adjustable jig styles. “I’ve never been satisfied with the various box joint jigs I’ve made over the years … Good box joints rely on the spacing and size of the cutter and indexing pins to match almost perfectly, usually within a few thousandths of an inch … Unfortunately, that rarely happens.” Plus, fixed-style jigs require a different template and guide pin for each joint size, so the number of possible joint proportions is limited by the range of templates a woodworker has.

Manufacturers have attempted to solve the problem of perfect fit by creating jigs that are adjustable, but Schaffter found them lacking for other reasons. He learned that just because a jig is adjustable doesn’t mean it can be accurately or reliably set, and the user must often resort to calipers or making numerous test cuts to set the jig or change the finger size.

Then about three years ago, while helping a fellow woodworker figure out how to make a box joint template for a dovetail jig, Alan resolved to give box joint jig designs more serious thought. “I just knew there had to be an easier and more precise way to do it,” he recalls, but the ‘Eureka!’ moment didn’t come until he clearly understood the geometry of how all box joint jigs must work. “I realized that even though the guide pins move different amounts, there is a fixed relationship between the amount they move from the cutter (dado blade or router bit). The challenge was then to figure out a way to capitalize on that relationship.”

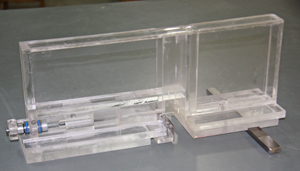

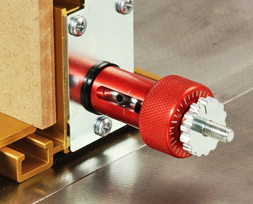

Schaffter considered a variety of mechanisms that could produce the setup mechanics for a better jig — common threaded rod, gears, belts, levers, a lead screw — but all of these would create unwanted complexity unless it was a single assembly. This was key. He designed a prototype utilizing a single dual-pitch lead screw with split indexing pins that would control the entire calibration process of the jig, “and the rest was history,” he says. The “very primitive” prototype jig worked as he hoped on both his router table and table saw, test cut after test cut. No calipers or tweaking were required, because the jig used direct transfer from the cutter and a workpiece instead of measuring tools. And, the mechanics didn’t depend on the precise width of the blade or router bit. It seemed clear that a better box joint jig was definitely possible.

But creating a better mousetrap doesn’t necessarily make it marketable. Alan did in-depth research on the patenting process next and learned a number of “shockers.” For one, a utility patent can cost upwards to $20,000 or more, most of which goes to patent attorney fees. None of those fees are refundable if the patent is denied. Additionally, it is nearly impossible for anyone but a patent attorney to successfully write and file a utility patent, given the “special but arcane” patent language that’s involved. Even if it is accepted, a patent is only as good as the amount of money the patent holder can devote to defending it. For an individual, that alone could be a significant roadblock. Finally, few companies will buy a patented design outright, due to high upfront costs and financial risk.

All things considered, getting a utility patent for his new box joint jig was out of the question. Equally unfeasible was trying to manufacture and market the jig himself, Schaffter resolved. The best solution was to file a Provisional Patent Application, which allows an inventor to use the term “patent pending” and establishes a date marker for a design, then seek a manufacturer with whom to license the concept.

“A license…is a vehicle to receive money for your design from a company who you license to produce it,” Alan says. But licensing has its price. Since the manufacturer takes all the risk and funds both the development and marketing of the design, the licensing fee to the designer is typically very small, ranging from one to five percent of the wholesale cost of the product. “Unless you invent an item with wide appeal beyond woodworking that has high volume sales, like an iPad or iPod, you are not going to get rich from a license.”

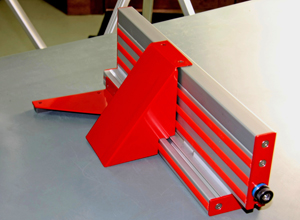

With Provisional Patent Application in hand, Alan contacted a half dozen woodworking accessory manufacturers and described his new box joint jig, offering to license it. All of them showed interest, he recalls, but it was Chris Taylor of Taylor Design Group and INCRA® Precision Tools that stepped up to the plate to license the basic concept and mechanism of Schaffter’s design. Once the details were finalized, serious development began in 2009.

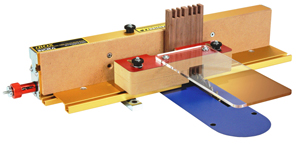

During the three years that have followed, INCRA and Alan exchanged more than 900 emails of engineering drawings, sketches, photos and analysis, in order to bring the INCRA I-Box jig to fruition and now, to market. Alan remained contractually involved throughout the process, without compensation, to consult and experiment with the evolving design. He says that his pre-production prototype now has “more holes than Swiss cheese,” after using it extensively for beta testing.

INCRA generated CAD designs for the extrusion profiles and other parts of the jig, as well as specs for parts suppliers. Their fabrication expertise helped to keep manufacturing costs down. INCRA also suggested the addition of micro-adjustment, which Alan devised and the company incorporated into the jig. Schaffter admits that it was Taylor’s wife Alice who came up with the name “INCRA I-Box,” which stands for “Intelligent Box Joint Jig.”

The entire process proved to be a collective effort.

“Obviously, this jig would never have been built without my initial functional discoveries and concept … but the jig as described in my initial drawings, specifications and prototypes was a long way from anything remotely manufacturable or marketable. Chris Taylor and the folks at INCRA Tools really brought it all together and made it what it is today … Without (those) efforts, it never would have seen the light of day.”

So far, it seems woodworkers who are using the new I-Box are reaping the benefits from the partnership and sweat equity that has gone into this new jig. Schaffter says that among more than six online forums he monitors, or in any magazine, there have been no negative reviews of the jig’s performance. The response has been “overwhelmingly positive.”

While Alan’s experience is proving to have a fruitful outcome, he has a few words of advice to offer. For those readers who might have a novel design for a new woodworking widget, Schaffter first recommends a reality check. “Be honest with yourself and ask: is it really needed? Are there other similar devices on the market and, if so, is yours that much better? How and why can it be manufactured easily, economically and profitably, or will people just make DIY copies of it?”

If you’re still convinced you’ve got a winner, make the best possible prototype you can to verify that your idea actually works, and do your CAD drawings. Learn all you can about non-disclosure agreements, patents and licensing. Evaluate the market, in terms of manufacturers who might want your design and who would be willing to fit it into their product line.

In other words, well-intended inventors, take the advice of a former naval commander who now knows how to navigate the choppy waters of product design: Do your homework.