About 12 years ago, chip carver SallyNye and husband David went to a carving show, where they spotted a little carved bird. They picked it up and brought it home — and soon, people who stopped by their house were commenting on it, saying they had seen one like it on their travels, to Budapest, or Scandinavia, or a number of other locales.

The search for the history of the bird, and re-creations of it, turned into a passion for Sally and David — and the equivalent of a full-time job. “We’re busier now than when we were working, but it’s meaningful,” said David. “We don’t have children; this is our mission.”

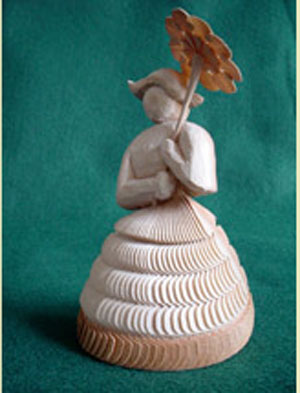

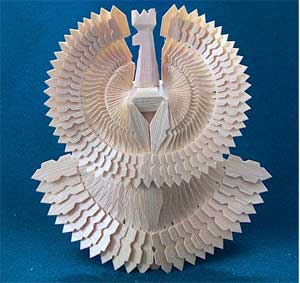

Both Nyes retired around 2000, and have spent much of their time since then in their pursuit of the history and legends surrounding the fan bird. What is a fan bird? It’s a bird carved from one piece of wood, with a “fan” carved — or, more precisely, rived (as the wood is split, not cut) — into it. “There’s no glue; it’s all just wet wood, turned and interlocked,” David said.

“There are three basic cuts per carving,” Sally added. Those cuts are “the interlock — the place where you put the feathers; the hinge — where you pivot the feathers; and the rive — the individual feathers. All those elaborate fan birds, are three basic cuts. Once the three cuts are done, the rest is all ornamental, you can do whatever you want.”

“You do need moisture in the wood so you can rive and slice the feathers,” David said. “You can’t do it when it’s dry; the wood has to have, long, straight fibers.” To meet those goals, the Nyes use white cedar for their wood. It grows only as an ornamental shrub near their home in southern Michigan, so some Amish men they know keep an eye out for the kind of wood they’re looking for in a swamp area in the northern part of the state. “For some reason, white cedar tends to grow in a slow twist,” David said, and they need straight pieces of 10″ to 12″ diameter, so they’ll harvest the straight trees in an area, then move on from there.

After the wood is harvested, they boil the wood to remove the sap, then freeze it and place it in plastic bags. “We ship it frozen, so it has moisture in it,” David said.

The Nyes ship wood, as well as fan carving tools and books, as part of their Fan Carvers World business, and they also teach classes. “We share all the information we have,” Sally said. “There’s no competitors as far as we’re concerned,” David added.

And they have a lot of information, compiled — so far — into two books, and incorporating European museum research from countries including Poland, Slovakia, the Czech Republic, Ukraine, Hungary, Romania, Finland (including Lapland), Germany, Austria and more. They’ve dated the fan bird, also known as the Holy Spirit bird, or bird of inspiration, back at least to the 1600s, and found evidence of it in areas ranging from Greece to Lapland. “It was in judges’ chambers, in people’s homes, in churches, in mountain huts…,” Sally said. “If they didn’t have a bird, it was painted on the ceiling.”

The traditional fan bird is a dove, symbolizing the Holy Spirit, Sally said. An oft-cited legend, found on the Fan Carver’s World website, traces its origins to Russia. When pulpits were introduced to Sweden in the 1600s, Sally said, a fan bird dove would be hung over the minister’s head, while a pelican carved in the same style would hang over the christening font. Sweden commemorated these fan carving birds in 1980s postage stamps.

The Nyes do make a variety of fan carved birds, with the main species being the dove, but “the pelican is on my to-do list,” Sally said. “I have a template.” The pelican’s symbolism relates to resurrection.

In many countries with an historic tradition of the birds, they weren’t allowed — or at least weren’t allowed to be referred to as Holy Spirit birds — during communist rule, due to the religious symbolism. Still, some of the birds remained, perhaps hung in a private altar in a closet that could be closed quickly. When hung, the air flows through the fan birds’ feathers, simulating movement.

Fan birds were also disseminated geographically via prisoners of war who moved through other countries, carving the birds, teaching others to do so, and calling the design the “bird of inspiration.”

Much of this information comes from the Nyes’ travels, discussions — both in person and online — with European museums, and ethnographic research, including translations of old documents and research into U.S. immigrants’ folk art. “Here in Michigan, the lumberjacks did [fan carving], but they didn’t know the history,” Sally said.

They’ve also taught the history of fan carving at European woodworking schools, and classes in fan carving at woodcarving shows. Sally, the main carver, teaches the classes and finishes the birds from wood which David has prepared and roughed out into a profile. “When we’re teaching students how to rive, it’s a fun thing to do,” she said.

When riving the feathers, the knife is splitting the wood, rather than cutting it, and the Nyes have developed two tools, in conjunction with Flexcut™, to make this easier: a 3″ draw knife, and a single-bevel riving knife (as opposed to a double-bevel roughing knife) to allow more control and better fiber splitting when drawing the knife down through the wood.

Much of their work, however, is devoted to tracking down the stories and the symbolism of the fan bird. “You could take any folk art and do this,” extensively, Sally said, but for the Nyes and the fan bird, “The whole story was just so fascinating, we couldn’t let it go.”