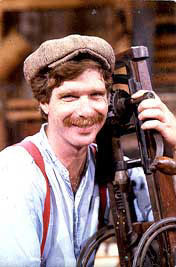

With his ratty cap, trademark suspenders, and infectious elan, Roy Underhill has been captivating audiences for a quarter century on the delightful PBS program “The Woodwright’s Shop.” Begun the same year as “This Old House,” it is the longest running woodworking — rather than home improvement — show on television, no doubt thanks to its charismatic host.

Behind Roy’s television persona is a charming, funny, highly educated woodworker with a passion for what he calls “creative work on the margins of society.” For decades, he’s been promoting the idea that we can learn some very sophisticated hand work technology from our forefathers, and do great woodworking without electricity. Looking at his past, you can see that the roots of his Luddite sensitivities started early.

“I was born in the nadir of 1950,” Roy mused, “just in time for television and Howdy Doody, on the December 22nd winter solstice, the shortest day of the year. As far back as I can remember, I always made things. My older sister was in college when I was a young child, and she worked at the Smithsonian on the ‘Life in Early America’ exhibit. I’d ride the trolley car down to visit her and see the log cabins and hand tools on exhibit. I simply assumed that this is how adults worked, and what they did for a living.”

Roy’s father, a federal judge in Washington, DC, and mother, an artist, encouraged him to follow his own path. “After all, I was the fourth child, and they already had two doctors and a scientist,” he joked. “That left me free to be whatever I wanted to be.”

Underhill got married in his senior year of college, then graduated from UNC Chapel Hill with a degree in theater directing. Along with other theater denizens, they moved out to Colorado to create a group called Homestead Arts. The venture failed miserably, so Roy and his wife moved on.

“We packed up our teepee and headed to New Mexico to work in a utopian socialist commune,” Roy recalled. “We lived up in the mountains, 17 miles from the nearest power grid. I became a self-taught blaster, beekeeper, and goatherd.” The blasting was more practical than you’d think. “I went down to Santa Fe, bought a couple of cases of dynamite, and working from a photo in the Whole Earth Catalog, started blasting for outhouses, the quickest way to dig holes in rocky, mountainous terrain.”

“Because we were so far from electricity, everything had to be made by hand. At the time, people were also starting to become aware of the environmental effects of using so much energy. I started rediscovering the ways people did things before electricity. If you wanted a hole, you used a brace and bit; if you wanted to cut, you used a hand saw.” Everything seemed to fit, but it was not long before the East Coast called him back.

“I came back east in the mid 70’s and went to Duke University for environmental studies. My work was on early technology; looking at how environment and technology affect one another.” He also looked at how tools evolved, blending an understanding of the grain and structure of wood with how wood behaves, all of which influences how tools are designed and made.

“Working with the wood exploits its strengths and weakness,” Roy explained. “You hew and split while it is weak and green, and use the strength and pattern of the grain and structure appropriately for what you are making. Felling the tree, milling, then working the wood makes one more of a whole woodworker.”

Instead of a more traditional master’s thesis, he was permitted to do a live presentation. His subject was “How to start with a tree and an axe and build your house and everything in it.” With tools in hand, he went out onto a hillside and did his show. “When I was done, someone said to me ‘That was pretty entertaining. You ought to do that on TV.'”

“There was an abandoned blacksmith shop at a nearby park owned by the city of Durham. I told them, ‘I’ll build a working shop and historic museum if you let me run it.’ I built it, called it ‘The Woodwright’s Shop,’ and started teaching workshops and making wooden items to sell.” It wasn’t long before he pitched the idea of a program to the local PBS station. They rejected it at first, but he did not give up. “A year later, in 1979, I went back with a toolbox, wooden rakes, a rocking chair, and my cap and suspenders. It may have been the fact that I also had an axe in my hand, but this time, they at least let me shoot a pilot.”

Dealing with the arts is often a waiting game, and it took an agonizingly long time for them to get back to him. “At the time, I was a new father with a daughter to support, and I needed income. I heard that Williamsburg, the recreated colonial town, was looking for a carpenter who could do things the old way, so I applied there.” Again he waited.

When Roy’s power and hand tools face each other in chess, he’s rooting for the hand tools.

“I was feeling hopeless and close to giving up,” he recalls. “One day, I was up in a tree trying to hive a swarm of bees that had moved, thinking ‘even the bees are leaving me.’ I got the bees in the hive, came inside, and the phone rang. It was PBS saying the pilot was accepted, and I had to start filming immediately. I hung up, and the phone rang again. This time, it was Williamsburg calling to offer me the job. I started both jobs together, developing a program at Williamsburg building houses the way they were done 200 years ago, and creating a television show on traditional woodworking.

“Working at Williamsburg was wonderful in that I could walk from a master wheelwright, to a master cooper, to a master cabinetmaker, to a master gunsmith, to a master blacksmith, all at the top level of artisanry, and just ask any question I had.” He stayed on as the master housewright for 10 years, teaching visitors how things were done and pressing them into service doing the work, and spent five more doing program development.

He eventually left in a disagreement over authenticity.

“We were building slave quarters, which, of course, would have been built by the slaves themselves. The architectural historians insisted on making the buildings look shoddy and poorly constructed. In reality, the slaves were the ones who did most of the work, and were most adept and skilled at such tasks. The architect insisted on poorly constructed chimneys, wood with bark left on, and other things that were supposed to make visitors feel sorry for the slaves, but none of this was realistic.” He objected, but the architects insisted, and won.

In reality, there were slaves with great levels of skill and craftsmanship, and one recent Woodwright’s Shop show illustrates just that. “One of the coolest shows we did this year was on John Hemings, Sally Hemings’ younger brother,” Roy explained. History tells us that Sally Hemings, a slave, bore a child to her owner, Thomas Jefferson, quite out of wedlock. “Jefferson hired James Dinsmore, a master craftsman out of Philadelphia, to build Monticello, his famed estate. Hemings, still a slave, apprenticed to Dinsmore, and became an extraordinarily skilled woodworker. When Dinsmore moved on to build James Madison’s home, Montpelier, Hemings stepped in as master carpenter on Jefferson’s retreat house, Poplar Forest.”

Hemings corresponded back and forth with Jefferson, then our president, dealing with a slew of construction and design details, a clear indication that Hemings understood a whole lot more than merely how to build. “There’s also a thoroughly ironic letter Jefferson wrote to Dinsmore,” Roy explained, “asking for the return of the astragal planes, gauges, and templates that Dinsmore had borrowed from Hemings. Here was a man who does not even own himself, but he owns tools that another master craftsman regarded highly enough to borrow.”

That sort of compelling blend of history and woodworking is part of the allure of Roy’s long-running series. He recently finished filming his 25th season, and has recorded some 163 hours of programming hosting such luminaries as Nora Hall, Toshio Odate, Frank Klausz, W. Patrick Edwards, Don Weber, Wayne Barton, and many of the craftsmen from Williamsburg.

“The show is almost too non-commercial, even for PBS,” Roy mused. “There’s nothing to buy, no product placement shots. To me, that is what PBS should be about.”

For the past two decades, State Farm Insurance has sponsored this one-take wonder, shot from beginning to end in real time with no editing. What you see is what is really happening. Consequently, it is not unusual to see Roy’s hands sport minor cuts and bandages, a function of rushing through the show. “The director kept yelling cut, and I must have misunderstood him,” jokes Underhill. “You know those yellow plastic wrist bands that say ‘Live Strong’? I wear one that says ‘Live Sharp.'”

Along the way, he’s found time to produce a spate of Woodwright Shop books, plus one on another love, communication. Called Khrushchev’s Shoe: And Other Ways to Captivate an Audience of 1 to 1,000 it talks about ways of keeping audiences involved with your presentation, something he obviously knows quite well. He’s currently working on an adventure novel set in the 1930s and featuring, among others, a misplaced bureaucrat who defeats a fascist plot while accidentally creating a highly popular woodworking radio program. Though he makes it look easy, he confesses that “working with publishers is like having your baby kidnapped by space aliens.”

Naturally, Roy keeps busy with other projects in his “spare” time. He recently trained actor Colin Farrell how to hew wood for “The New World,” an upcoming Terrence Mallick movie about the Jamestown settlement of 1607. He also set up the pit saw and most of the tools, and appears as an extra in the film. Roy says the film, shot on location near Williamsburg, is groundbreaking in terms of getting things honest. If you go to see it, look for a starving English settler with a saw, axe, or drawknife in his hand, and a fake beard on his face.

Clearly, Underhill keeps busy, frequently in encouraging others to indulge in what he calls “subversive woodworking.” He’s quick to suggest that we can all benefit from slipping back toward the days when the term “energy consumption” meant food and drink.

“With a jug of muscatel and an axe,” Roy chuckles, “you, too, can be part of the alcohol-powered woodworking trend. Call it ‘woodworking beyond the Norm.'”