In January 2014, Steve Purtell and Gus Kanakis made a discovery at the Veterans Memorial Auditorium in Lowell, Massachusetts: a Civil War flag and carved frame. Steve Purtell said, “We found the flag leaning behind a piano one day in basement storage and knew there was much more history behind this unique piece. I have never seen anything like it before.”

They brought it to the attention of the Greater Lowell Veterans Council, then under Commander Bob Page, which jumped into action to restore the flag and 73” wide x 54” high frame, bringing it to Camille Breeze of Museum Textile Services in Andover for the restoration of the flag itself and to Melissa Carr of Masterwork Conservation in Arlington for the restoration of the frame.

The story behind this flag began when 24-year-old Solon A. Perkins joined a cavalry unit, the Independent Battalion of Massachusetts, later becoming part of the Third Massachusetts Cavalry. Perkins was commissioned on February 20, 1862 and was killed in a skirmish on June 3, 1863 in Clinton, Louisiana. After his death, the flag was sent to his mother. Lowell historian Richard Howe says, “We can’t know for sure, but I believe he was so highly regarded by his men that they sent the guidon to his mother as a special honor for her.” Mrs. Perkins kept it for many years, later giving it to Charles Knapp, a banker at Lowell’s Middlesex National Bank, who commissioned the elegant frame.

The main purpose of a “guidon” flag is to literally “guide on” the troops. Soldiers would know where and when they were to move by watching their flag. Historian and consultant Steve Hill, of the Dupage Military Flag Company, said of the piece, “Clearly this particular guidon, judging by the magnificent job of framing, was very important to those who originally carried it.” He also clarified that this particular type of guidon was common after 1862. “At the beginning of the Civil War, guidons were simple swallowtailed flags of two colors: the upper half red, and the lower half white. The Union guidons were redesigned as small, swallowtailed versions of the Stars and Stripes.”

When conservator Melissa Carr started the project, she did a thorough evaluation of the frame, which was actually two frames, one inside the other. There were three phases: cleaning, stabilization and loss replacement. She also had to analyze the carvings. Were the carvings of the military equipment replicas of actual weapons or simply approximations of carbines, sabers, etc.? The carbine, for example, was missing the trigger, trigger guard, sight and hammer assembly. The Internet was a valuable resource, yielding photographs in enough angles to be able to reproduce the missing parts and identify it as a Joslyn .52 caliber carbine, model 1862 or 1863. Whoever carved it had also carved the backs of the attachments as well as the front. They were in 3D, even though those sections would not be seen.

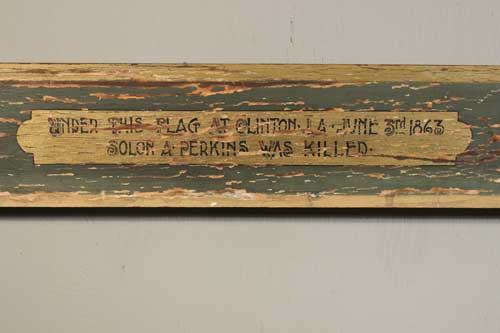

The quality of the frame has led to speculation that it might be the work of master nineteenth century carver, John Haley Bellamy, who was in the area at the time — but that might never be known for sure. At the bottom rail of the inner frame (paint restoration by Adeline Myers) are the words “Under this flag at Clinton, La., June 3, 1863, Solon A. Perkins was killed.”

Historian Richard Howe says, “The guidon is a tangible object that was with these men in Mississippi, many of them from my home city of Lowell. I regard it as a way to communicate with the past.”

Conservator Melissa Carr says, “What struck me from the beginning and all along the project is the caring attached to this flag and frame. The men originally with Perkins cared enough to save this flag. How did his mother feel when she received the flag? What were the circumstances that she gave the flag to Charles Knapp? Was she dying? There was a huge amount of care initially, then 120 years later, the Veterans Council’s care. The veteran’s group came into my studio as if they were carrying a newborn baby. The word legacy is overused, but people have kept caring about this flag and frame.”

At presstime, the Greater Lowell Veterans Council had raised $9,400 toward the $15,000 restoration costs. Further information can be found in their video here.