This article, “Turn an Elegant Tealight Candleholder,” is from the pages of American Woodturner and is brought to you by the America Association of Woodturners (AAW) in partnership with Woodworker’s Journal.

Like most woodturners, I make gifts for friends and family. I like to see these gifts being put to use. These simple tealight candleholders are a good example—they are popular and get used!

Prepare Materials

This article will describe how I make a tealight candleholder, but the concept can be applied to designs of your own choosing. The basic design uses a glass cup, 2″ (5cm) in diameter and 1-1/4″ (32mm) tall. An Internet search for “glass tealight holder” will provide plenty of purchasing options. Just be sure your design includes a glass cup, which catches any melted wax and keeps the flame from reaching the wood.

You can use any hardwood as long as it is dry. My design uses nominal 1″- and 2″- (25mm- and 5cm-) thick hardwood lumber. For the candleholder shown in this article, I used bubinga and wenge, a contrast in color, and maple veneer between the two. The photo shows the components cut into squares: a 3″ (8cm) square of maple veneer, a 4″ (10cm) square of bubinga for the top section, and a 2-1/2″ (6cm) square of wenge for the base, or foot.

Center mark and draw a maximum diameter circle on each piece. Next, drill a hole 2″ in diameter and 1″ deep in the top section, which will receive the glass cup. I drill this hole on a drill press, using a Forstner bit. Hold the piece safely in a wood screw clamp, and set the drill press at its slowest speed.

Trim the top and base pieces round on a bandsaw, following the circles drawn earlier. Trim the veneer round with scissors.

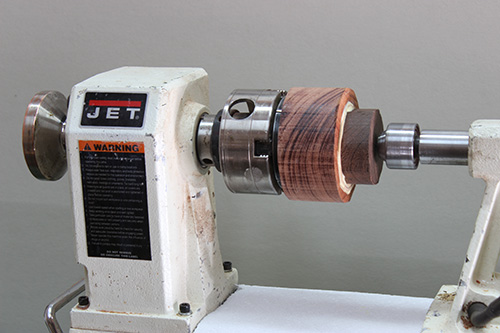

Now you can glue the components into a single blank, using the lathe as a clamp. Begin by mounting the top piece on the lathe using your chuck in expansion mode. Note: It’s a good idea to check the holding range of your chuck jaws prior to drilling to ensure you’ll be able to mount the piece this way. Most standard jaws will fit within a 2″ hole. If the closed jaws won’t fit in the hole, drill a slightly larger hole or use pin jaws in your chuck.

Ensure the mating surfaces are smooth and flat. I use a belt sander to true the surfaces, but you could also use sandpaper glued to a flat piece of plywood. Apply glue and clamp them together. One common problem is the tendency of the pieces to slip out of position when the glue is still wet. The point in the live center helps to prevent this. Let the glue set overnight.

Turning

Dry hardwood requires sharp tools. Lightly sharpen or hone them often. With the blank still in position from the gluing step, check that it is held snugly, but be cautious when holding any piece in expansion mode—too much outward force can break it open. I always use the tailstock for additional support.

Use a spindle-roughing gouge to turn the blank round. Then turn a tenon on the base, so you will now have the ability to hold the blank securely from either end. Remove and re-mount the blank, gripping the tenon in the chuck.

For this design, I mark a line around the center of the top piece. This is a useful reference, as I begin shaping from the center down to the drilled opening at about a 45 angle. I use a bowl gouge, followed by a negative-rake scraper. When you are happy with the shape of the top side, reverse the blank again, holding it once more in expansion mode.

But be aware that since you’ve removed some wood near the top, that area is now weaker. Expand the jaws carefully, and use tailstock support. Using a bowl gouge and scraper, turn the bottom half as you did the top. Turn the base to a diameter of about 2″.

Once again, reverse the piece in the chuck so you can complete the top. I like to add a few grooves using the long point of a skew. The grooves can then be “burned in” to darken them. Rather than using a burn wire, which can be difficult on a sloped surface, I use a scrap of Formica laminate.

With the lathe at high speed, press a curved edge of the laminate into a groove. When you see smoke, the burn line is complete.

Do a final check to ensure the glass candleholder fits into the opening. If the fit is tight, enlarge the hole with a scraper (I use a round carbide-tip cutter).

Finishing

Sand the candleholder, then reverse the piece in the chuck one last time. At the tailstock end, part off the tenon and finish turning the base carefully. Pull the tailstock out of the way to complete the sanding of the bottom.

To finish the piece, I apply sanding sealer, smoothed with steel wool, followed by two coats of friction polish to give it a mellow gloss.

Bill Wells is a retired engineer living in Olympia, Washington. He has worked with wood in one way or another most of his life and is now a member of Woodturners of Olympia, an AAW chapter.