This small puzzle box doesn’t eat up a lot of material, it’s fun and a little challenging to make but won’t keep you in the shop for weeks, and it will appeal to anyone who tries to open it.

It’s symmetrical, with interlocking dovetail slides and keys. The sides are alike, as are the ends and the top and bottom. Which is really the top? How do you get it open? The answer may not be immediately obvious. For now, don’t try to solve it. Think about getting it made.

You’ll only need a couple feet of stock, depending on board width. So rummage through your stashes of scraps too good to toss. Joint and plane all the stock for the box to a 1/2″ thickness. Rip the sides and ends to width, and crosscut these four parts to length. Make sure you have some decent sized scraps, thicknessed along with the good stuff, to use for dialing in setups. Set the rest aside for now.

Making Rabbeted Miter Joints

I elected to use rabbeted miter joints to assemble the sides and ends. The joint’s benefits are its clean appearance, its improved stress resistance over a plain miter joint, and particularly its ease of assembly. You can cut mitered rabbets on the table saw, but it’s less intimidating to make them on the router table. You’ll need a bit to cut rabbets and a chamfering bit to add the mitered ends.

The sequence, as shown in the photos, is as follows: First, you rabbet the parts. Then you bevel the ends of those rabbets — in effect, mitering them.

The depth for all the rabbets is half the stock thickness, in this case 1/4″. Put a straight bit in the router and carefully adjust the depth of cut to 1/4″. Make a test cut on a piece of the setup scrap; rip the scrap in two and put the pieces together in a shiplap. The faces must be flush with the bottoms of the rabbets tight together. If you’ve got a gap between the rabbets or if the faces aren’t flush, tweak the bit height and cut a new test. Then set the fence for the first round of rabbets.

The rabbets cut across the ends of the box sides are half the stock thickness in width, or 1/4″. Slide the fence into position, and use the final depth-of-cut test piece as a gauge in setting it. You want only enough of the bit exposed to cut as wide as the depth. Again, confirm the accuracy of the setup with test cuts.

Rabbet the ends of both side pieces, backed up with a good-sized pusher to guide the workpieces through the cuts.

Now alter the setup for rabbeting the box end pieces. These rabbet widths match the stock thickness exactly. Using an end piece as a gauge, shift the fence to expose more bit. Once again, confirm the accuracy of the setup with test cuts. That done, cut rabbets across the box ends.

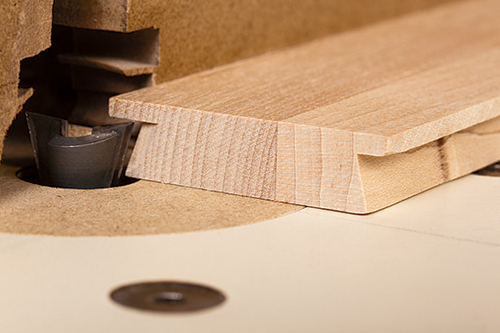

Beveling the Rabbets

The bevels (or miters) are routed with a chamfering bit. When you fit the bit in the router, be sure to extend it far enough out of the collet. The bottom of the cutters must be 1/4″ above the tabletop to mill the bevels. As you adjust the height of the bit, use a workpiece to gauge the precise elevation. The terminus of the angled cutting edge must align with the rabbet bottom. Similarly, adjust the fence so only enough of the bit is exposed to cut the thickness of the rabbet projection.

Confirm your setup using the final rabbet test-cut scraps. Make any necessary adjustments before cutting the good parts. Back up the cuts to prevent blowouts.

After sanding the parts and checking the fit, I assembled the box with glue, clamping it with a band clamp and four shop-made corner blocks. To make such blocks, cut a rabbet in a 1-1⁄4″-square strip, then chop it into four pieces, each about 2″ long. Wax the faces of the rabbets so the blocks don’t get glued to the box. As you tighten the band, measure the diagonals to ensure the box is square — you may need to coax it.

Make Rabbeted Tops and Bottoms

After the glue sets, pop off the band and corner blocks, clean up the edges of the box, and rip and crosscut the top and bottom to fit the box you’ve now got. I cut the two parts using a cutoff sled on the table saw, and I used the box assembly to set a stop for ripping, then crosscutting the parts accurately.

Cut 1/8″-deep, 1/2″-wide rabbets around the top and bottom (see Drawings), so these parts set slightly into the box. Glue the bottom to the box (not the top).

Rout Slots, Slides and Keys

I routed all the dovetail slots, grooves, slides, and keys with a 3/4″ 14° dovetail

bit. I cut the wide slots in the box ends first, then routed and fitted slides to them. Put the bit in the router and adjust the cut depth to 3/8″. Plan to make the slots about 1-3⁄4″ wide (precision here is irrelevant). Set the fence 15⁄16″ from the tip of the cutter for the initial cut. Using its rabbet, position the top on the box. To prevent blowout damage, cut two pieces of scrap to cover the top and bottom. A clamp holds the package together and ensures you slide the same side of the box along the fence on each cut.

Make a first pass, routing a dovetail groove through one end of the box. Then roll the box end-for-end and make a duplicate groove through the other end. Adjust the fence about 5/8″ further away from the bit and make second passes though both ends, widening the slots. A second fence adjustment and third cuts should be sufficient to complete the slots.

To make the slides, cut a strip of 1/2″-thick stock about 2″ wide and 7″ long. Leave the depth-of-cut setting unchanged, but move the fence to house the bit almost completely. A shallow first pass along each edge of the blank establishes the dovetail angle but leaves a shoulder above the bit to bear against the fence. A multi-pass cut-and-fit process, shifting the fence, whittles down the dovetail section without affecting the overall (fence-bearing) width of the blank.

Once the blank fits easily into either slot, cut it into two slightly overlong slides. Clamp the box in your bench vise, with a scrap tucked in to hold the slide in place, as shown. Plane down the slide flush with the box end’s face. Turn the box over and repeat the operation to finally fit the second slide. Sand the ends of the wide slides flush with the top and bottom of the box. Glue the slides to the box top (and only to the top, not to the box itself).

With them in place, you can now rout the key grooves across the box top and bottom. Milling them repeats the earlier process for routing the wide slots. Clamp scrap against the wide slides to prevent exit damage. Lower the bit to cut only 1/4″ deep, and set the fence to locate the groove in the center of the box. Plow grooves across the box top and bottom.

Make the keys the way you did the wide slides. Resaw or plane a 1″-wide strip of stock to 3/8″ thick. Rout the edges and fit the keys into the grooves. Plane them flush and trim them to exact length.

I applied Waterlox for finish, allowing it to dry for several days before rubbing it out with wax and #0000 steel wool.

Solution Step of Construction

The solution to the box’s puzzle — how to open the thing? — is in the limited movement of the bottom key. It moves clear of one slide, but then stops with its far end sticking out. That movement aligns tiny notches in the key’s edges with the dovetail notch in the adjacent slide. Pull the top up, and the slides (they’re glued to the top, remember) pull up and off with it.

The key’s movement is governed by a 1/8″-dia. dowel pin projecting into a short slot in the box bottom. Fit it by pulling the key out of the bottom and laying out the ends of the slot on the centerline of the dovetail groove. Drill the ends of the slot with a 3/16″ bit and then waste the material between them. Reinsert the key, aligning its ends flush with the box ends, then transfer the near slot end location to the key with a transfer punch or drill bit. Move the key to what will be the limit of its travel and score its edges to mark the two notches that must be pared. Pull out the key and drill a stopped 1/8″-dia. hole at the mark, then pare off the dovetailed edges. Reinsert the key, glue the pin into its hole, and fit the top and slides in place.

I left the key in the top unglued, as a kind of diversion. The key comes out, but the box just doesn’t open!