I’ve been a woodworker and a fly fisherman for years, so it was probably inevitable that sooner or later I would build a bamboo fly rod. Inevitable, perhaps, but not necessarily a walk in the park. It cost me a fishing season. I broke rods long before they left the shop. I made rods that worked better as tomato stakes. I fried one rod to a crisp. I suffered epoxy failures and polyurethane busts. In short, I enjoyed every minute of it and, three rods after I started, I have a rod that I’m not ashamed to show to the world.

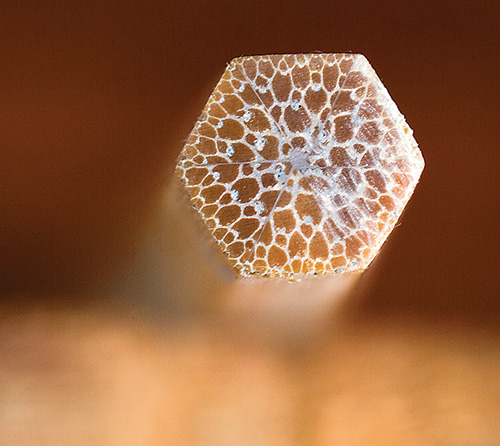

A bamboo fly rod is made of six strips of bamboo glued together to form a hexagon. The strips are triangular in cross-section, and since the rod tapers from handle to tip, the triangular strips taper, too — the triangle is bigger at one end of the strip than the other.

All of this is done in three stages: First, you rough out a rod blank, splitting the bamboo stem to stern, kiln-drying it, and then planing it into long triangular strips — a set of six strips for each section of the rod. In the second stage, you taper the triangular strips with a block plane and a special metal form. Then you apply glue to the pieces and clamp them together by wrapping them tightly with thread.

On a good day, it’s a piece of cake. On a bad day, it’s worse than getting skunked on the stream. Far worse. The final stage is applying the finish and attaching the hardware. I like to think of the stages as lumberjack, cabinetmaker and finisher.

Stage One: Lumberjack

This stage begins with a piece of Tonkin cane, the only cane used in rod-making, because its long, dense fibers make for a powerful rod. In the entire world, Tonkin cane grows in a single 30-square mile patch of China.

Technically, bamboo is a grass, and a stick is called a culm. The easiest and fastest way to get the strips you need is to split the culm the way Windsor chair-makers rive a chair back from a log, and for the same reason. Splitting bamboo gives you a piece with long parallel strands of grain. Rod-makers often make their own splitters that they drive into the end of the culm. Mine are chisels with edges that are ground to a rounded point. As the pieces get smaller, I hold the end of the chisel on the bench with one hand, and feed the bamboo into it with the other. The goal: six strips plus whatever else you can get from the bottom five feet of the culm. This will be the butt section. The tip comes from the upper five feet of the culm, and because rods traditionally have an extra tip, you’ll want to split it into 12 pieces.

At this point, a couple of minor adjustments are required. A stick of bamboo is divided into shorter sections by a series of bumps, called nodes. You need to get rid of them and deal with the bends that typically occur around them. Fortunately, bamboo bends when heated. Holding the node directly over a heat gun until the wood is almost too hot to handle makes the heated section bend like warm plastic. Once I’ve heated it, I can flatten the node completely (or almost so) by clamping it in a vise with the outside face against a jaw. I count to 10 as I clamp the edges between the jaws to straighten out the bends. If any of the nodal bumps remain, they’re sanded out by hand with 240 grit paper and a hard rubber sanding block.

Before shaping each piece into a triangle, there are two more steps. The first is to get each piece down to a manageable width. Traditionally this is done with a hand plane — it may be a grass, but bamboo works like wood. Tradition has its place, but this isn’t really the time for it. I rip the strips to width on the table saw (use lots of featherboards), and then I plane them into triangles on a jig in the planer. The planer jig is a simple oak auxiliary table with 60˚ grooves routed into it. Battens on the bottom fit snugly against the front and back of the planer bed to hold the jig in place. Each groove is slightly shallower than its neighbor — the largest is about 3/8″ deep and the smallest is about 1/16″ deep. I feed all the strips into the first groove, flip them edge for edge, and then feed them into the next shallower groove. I slowly work my way down the table until I’ve planed the strips to the exact size required by the rod.

Like any piece of lumber, your strips of bamboo need to be kiln-dried. This not only drives out water that might haunt you down the road, but it also tempers the bamboo, turning what would otherwise be a soft rod into one with backbone. It doesn’t take long — about 10 minutes at 350 degrees for the butts, and slightly less for the tips. I use a heat gun, combined with a couple of heat ducts — one inside the other — with lots of insulation around the outer pipe.

The heat gun shoots heat down the outside duct; it rises into the inner duct at an even temperature. I use two meat thermometers, one at the top and one at the bottom of the ducts, to monitor the temperature.

A Custom-Built Rod-maker’s Plane

At some point early in your rod building, the edge of your plane will dig into the planing forms you’ve just spent a small fortune to buy. Everyone does it, and no one likes it. But special rod-maker’s planes give you the control you need to avoid gouging. They have a groove milled down the middle, creating two outside “rails” that glide along the form. The groove travels over the bamboo, and the blade extends just far enough to do its work without cutting into the planing form.

The only rod-maker’s plane on the market is a beautiful piece of work, but you’ll pay for it. Instead, I made my own by routing a groove along the sole of an old block plane first, then on a good one I currently use for this task. I used a 5/8″ straight bit in my router table and set the distance between the bit and rail to 1/2″ — the width of a rail. Raise the router bit to make a cut about .001″ deep. When everything is right, take the blade out of the plane and run the plane across the spinning bit, holding it tight against the fence. Turn it around, and make a pass with the other side of the plane against the fence. Raise the bit and repeat until the groove is .003″ deep.

Clamping Up: Rod-maker Style

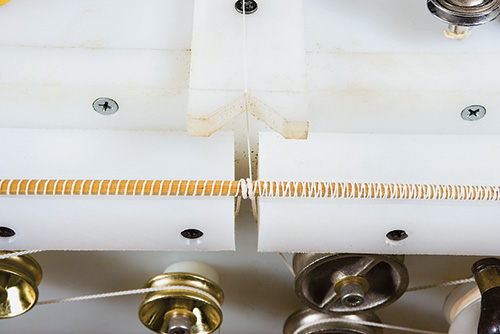

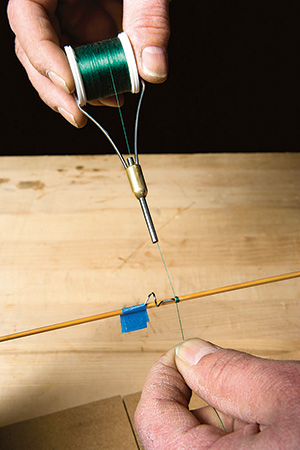

The strips that make up a fly rod aren’t going to clamp together with even the best clamps, so rod-makers clamp them with a shop-made jig (designed by Everett Garrison) that binds the pieces together in taut, spiraling wraps of upholstery thread. Glue is applied first, using a toothbrush to spread it over all six strips, which are lined up side-by-side on top of a piece of masking tape. You roll the pieces together and then run them through the binder. A drive belt made of kite line turns the rod and moves it forward as upholstery thread, fed from above, wraps tightly around the rod.

The fishing weights hanging from the drive belt determine the pressure with which the string is applied. On a tip as tiny as this one, as I discovered, the weight of anything more than the pulley is enough to snap the rod until you get a good 10″ from the tip. At that point, I add a 12-ounce weight. I use a 16-ounce weight on the butt section.

Once the rod is wrapped, you remove any twists, and then roll it under a board, a J-roller or both, to straighten it. I set it under weights on the planing form to keep it aligned while the glue cures. There will still be minor twists and bends when the glue dries, but you straighten them out with with gentle heat from the heat gun.

Stage Two: Cabinetmaker

Here, tradition rules, and I am fine with it. You are working with a finely tuned plane, a razor-sharp blade and a tapering jig that adjusts to thousandths of an inch. I enjoy it the way I enjoy fly casting — nothing matters but what you’re doing, and what you’re doing is about as good as it gets.

The fact is that while there is no perfect taper for a rod, there are thousands of bad ones. I chose a time-tested taper developed by Everett Garrison. Garrison made some 700 rods from 1927 until his death in 1975, and they are considered some of the finest ever made. I copied the 7-ft. rod he used on the last day he went fishing. Some of his other tapers, as well as his directions for building, can be found in his book A Master’s Guide to Building a Bamboo Fly Rod, coauthored with Hoagy Carmichael. Understanding how rod-making works means understanding how the tapering jig works. The tapering jig, also called a planing form, is made of two bars of steel 5 ft. long. The edges that face each other are chamfered and form a V-groove when the bars are put together. At one end of the jig, the chamfers form a deep valley; at the other end, they form a shallow valley. In between, the chamfer forms a valley that slopes evenly between the two ends. The bamboo sits proud of the jig, and you plane it until the plane is riding on the jig. When it is, the bamboo is the same shape as the valley — wide at one end, narrow at the other. Because of the hundreds of different rod tapers, you can adjust the depth of the valley every five inches using a pair of bolts. One bolt pushes the metal bars farther apart, the other pulls them together.

Setting the forms to the proper taper requires two tools from the machinist’s trade — the dial caliper and a depth indicator with a pointed tip. Initially, you set the forms with a depth gauge and, after planing a test strip, you check the setting’s accuracy with the dial caliper.

Gluing the Rod Together

When the strips have been planed to final dimension, it’s time to glue them together. Initially, I used polyurethane glue. It is widely available, affordable and waterproof. It fills gaps, has a working time of 20 to 30 minutes and dries the same color as bamboo. Unfortunately, 20 to 30 minutes isn’t a lot of time when you’re trying to clamp up six pieces of bamboo only slightly thicker than the butt end of a leader. The pieces slipped, slid and twisted as I worked, and to make a long story short, the polyurethane rods were the ones that became tomato stakes. I use industrial epoxy now, which is surprisingly friendly — it dries slowly, so if I have a problem I have hours to solve it.

Stage Three: Finisher

All that remains is putting the ferrules, handle, reel seat and line guides on. Ferrules first: The inside diameter of the ferrule is less than the outside diameter of the rod, so you file down the ends as the blank turns on the lathe. You’ll need a three- or four- jawed chuck and a support to keep the far end of the blank from whipping around. I made my support by bolting a piece of plywood to a table saw outfeed stand. Drill a hole in the plywood, line it with something soft (like a cork with a hole drilled in it), and then feed the rod through the hole to steady it. The handle and reel seat get glued on next — I suggest ready-made ones for your first rods; learn to make your own later.

Finishing, as a friend observed, is half science and half snake oil. Garrison hit upon the method most rod-makers use today. He dipped the rod, narrow end down, into an upright pipe filled with varnish, and pulled it out with a motor running at 1 rpm. This requires a pretty tall ceiling. I don’t have one, so I began to think about the last days of each semester in my college woodworking courses, when the shop smelled of Waterlox and Watco. It was the dustiest place on the planet, and yet because we were using oil-based finishes that we wiped off, we could still get blemish-free finishes. So far, I’ve finished my rods with Birchwood Casey® TRU-OIL® Gun Stock Finish, a pure tung oil that is also traditional rod finish. I apply it with a rag, rub it for about five minutes and set it aside to dry. If there are any imperfections, I sand them out gently with 1,000-grit paper. After three or four coats, the finish rivals the smoothness of varnish.

If you start in the fall, and make no tomato stakes or start no fires, it will probably be early January by the time you apply the several coats of varnish that hold the silk thread in place. Around here, it will be a couple more weeks before the blue-winged olive hatch. See you on the stream.