Paul Lemiski primarily builds chairs: “Ninety percent of what I do is rocking chairs, dining chairs and bar stools,” he said. He sometimes hears people say that a chair is the hardest thing to build, but “A chair to me is actually fairly simple, because it’s what I’m most comfortable with, and what I do. It’s my comfort level: what I first learned from is a chair.”

Well, maybe not actually the very first project he learned from. Paul credits his original interest in woodworking to a “really great shop teacher” in high school — and perhaps, to having anolder brother who passed on some wood from his WoodMizer sawmill to student Paul. “Other students were making birdhouses, but I made a rolltop desk,” Paul said. “Obviously, I made mistakes.”

He also took a bit of a detour after high school, going into business for a while selling auto and marine equipment, alarm systems and remote car starters. (He does live in Canada.) In 2008, his horse farm owner father needed some picnic tables. Paul made him 14 — and that was the catalyst to get him back into pursuing woodworking, this time as a business.

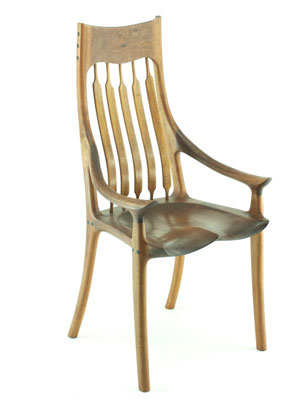

Around this time, Paul found a book about Sam Maloof. “I fell in love with his style and his work ethic.” He purchased instructional materials on making Maloof-style and spent around 500hours making his first chair, which he gave to his grandparents. “I determined that I was going to make at least 10 chairs before I charged the actual value of the chair,” so the first 10 mostly went to friends and family, Paul said.

He’s now up to 47 chairs. Although some are a combination of “a bunch of different woodworkers’ skills and ideas,” Paul said, “I’m most proud of the pieces I’m able to design myself.” Most recently, that was Dining Chair No. 9, which he describes as “modern Dutch style, clean lines, it stands straight up and down. I finally hit it just right.”

Paul himself now owns a small sawmill, which means, when it comes to his projects, “I’m able to make it myself, from cutting the log, and then to be able to design it as well as adjust as I make it, is something unique to woodworking, unique to my shop.”

As he cuts those logs, Paul mostly works with cherry, walnut and maple, which are all local to him in the Toronto area. His favorite among these is walnut: “Every time I dress it and take away the sawmill marks, it’s unique. Every piece is different, even from a few inches away in the same tree. It opens my eyes to how big the world is.”

He will also use small pieces of exotic woods in places like the back braces of his chairs. A local lumber dealer friend is starting to get in what Paul describes as “some interesting woods from Nicaragua,” which have not yet hit wide markets. Among them are chocolate tiger, ipe light and maca wood. “I’m able to use a very little bit of the rainforest to add a little bit of music to my chairs.”

Paul also uses Gabon ebony, and black and white ebony, to create his screw plugs. “My long-grain to end-grain joints all get reinforced with 4″ screws,” he said.

“When you’re trying to run a business, you have to find a balance between man and machine,” Paul said. He does his cutting by machine, and much of his shaping by hand. His table joinery employs the tongue-and-groove method, as well as miter joints reinforced by floating tenons, created with the Festool Domino tool.

“With all my chairs, they’re generally designed around the Maloof joint,” Paul said. “There’s a notch in the corner or side, then a tongue is created which is integral to the seat itself, which precisely aligns to the legs. It’s very strong.” Due to that strength, Paul is able to build chairs that don’t have any stretchers. “They’ve got very modern, clean-looking legs,” he said. “I have seen chairs with stretchers glued in too tightly, so that the seat can’t move, and then that leads to problems. My chairs are able to breathe with the changing seasons.”

One tool that’s been used on the roughly 200 chair seats that have come through Paul’s shop is the Kutzall Sanding Disc for an angle grinder. “It’s like somebody took a handful of sand and threw it at the wheel, except instead of sand, it’s carbide,” Paul said. “The wheel never wears out, so you’re not throwing away all that sandpaper trash. It’s environmentally friendly and very safe.”

When using it, though, “knowing how much wood to take off is where experience comes in. “If one person grinds a seat, it might be four hours of sanding, whereas if another person does it,it’s 40 minutes of sanding.”

Paul’s had the chance to observe this, because he’s now teaching his own students how to make chairs. “A lot more people can build furniture than can actually afford to buy furniture,” he said. “Getting a saw blade on wood and making sawdust is the only way you’re going to learn some woodworking.”

So, he’s teaching, “even though I still have questions — I’ve only been at this for about four and a half years — and I still have a lot to learn.”

In fact, one of the pieces that Paul considers the most special is a double rocking chair he made as a wedding gift for a friend he’s known since preschool. It’s engraved underneath with the date of the wedding, and has now withstood regular use, children climbing on it, and more. “He’s 30 years old, same as me,” Paul said of the friend.

As he makes his chairs, “It means a lot to me, to see pieces stay in a family for years, maybe even get passed down,” he said.