Many years ago, I found myself with some friends in an Amish-owned store in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, looking at seed corn. The corn was coated in brightly colored purple powder, and I said to no one in particular, ” I wonder why it is coated in purple powder?”

An Amish clerk hovering nearby answered. “That’s poison, so the birds don’t eat it before it can grow.”

“Well, I’ll be damned!” I replied, thinking how clever that was.

“No doubt you will,” the clerk said rather pointedly as he turned and walked away.

The Amish and Mennonite sects, who adhere to a strict religious code of behavior, are well known for both farming acumen and woodworking skills. While farming can be done by self-sustaining family groups, the business of woodworking demands a wider sales market. The “plain people,” as they call themselves, separate themselves from those outside their religion, whom they call “the English.” Consequently, they have an obvious and serious marketing problem. Mennonite Furniture Studios is a web site and sales arm set up to overcome that hurdle.

While the Amish avoid any connection with the outside world, including the use of phones and electricity, some Mennonites walk a fine line between separation and limited communication with the English. Ethan Zimmerman, who works in one of the shops represented by this curious web site, was willing to speak with me via phone. Ethan and his father are on the grid, meaning they use electricity that they do not generate themselves, and they use a phone. In contrast, many of their employees use neither. Our conversation was very pleasant, but there was a subtle overtone to it that called to mind that incident in Lancaster.

“That web site is a separate entity,” Ethan was quick to point out. “We do not run it, but rather contract with someone who connects us with the outside world. The challenge that the plain people face is deciding where to draw the line. Our connection to the web site is strictly to tap into a wider market for our goods, allowing us to do the woodworking.” The web site represents not only the chair making company set up by Ethan’s father, but other artisans who prefer not to be on the grid as well.

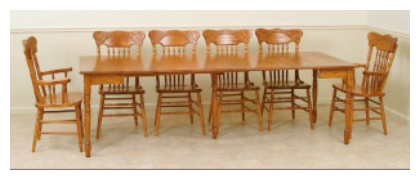

“Sixteen years ago, when I joined the business, there were three or four people working here building chairs and tables,” Ethan recounted. “I started by making chair parts, and learning what it takes to make high quality, strong products. Right now, we have eight employees i house. Ten other cottage industry groups, which average three or four employees each, make other goods to our specifications. In short, our web site represents some 40 Amish and Mennonite artisans. They want to cut wood but not deal with the customer, so we do that for them. We also do finishing for most of them, another thing many don’t want to do, in part because it can be a health hazard if not set up right.

“We make two categories of furniture. Our Heritage line contains adaptations of traditional furniture that may be redesigned for functionality. My philosophy is to copy a design proven to be attractive, then modify it as needed to make it comfortable and make sure that it is strong and up to the rigors of today, right down to the finish.

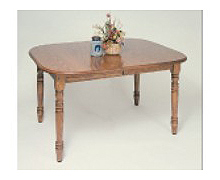

“Chairs not only look good, but are strong and comfortable as well. Our tables move smoothly enough so they can be opened at least halfway from one side. One of our inventions is our Eency-Weency Extension Table, which goes from a mere 30 inches when closed, to 126 inches when open and filled with its eight leaves. It even comes with its own leaf rack. Some tables, like our oval table, will store four leaves inside it.

“Our other line is our Classic line, which I favor. It contains accurate reproductions of historic pieces. If you go and buy an antique and see the hand-cut dovetails and plane marks, you have more respect for the craftsman that built it. I also like to imagine life in that time period. I have a washstand in my house that I bought without knowing it was an antique. I found out later that it was from the early 1800s, before the Civil War and before the railroads crossed the country. I feel a connection to the past with this piece. I really enjoy that part of it.”

What struck me, though, was not so much what they make, but rather what they do not make, and why. “In this shop, we make chairs, tables, desks, beds, china cabinets, and so on,” Ethan explained. “In short, almost any household furniture. However, we do not offer entertainment centers, as we can’t be comfortable with our conscience selling something like that. We also do not make poker tables, bars or other pieces involved with things we don’t feel comfortable with.”

Why draw the line there? “We believe we should cherish our bodies, which belong to God,” Ethan intoned. “Overeating, drinking alcohol or smoking is not accepted. Television and radio are shunned as harmful to the mind. We do read daily newspapers. That’s one of the lines we draw.

“The challenge for the plain people, especially Mennonites who use some technology, is how to use things like the Internet, which we need for business, without it tainting us. Historically, the plain people were agrarian, but that is changing. Because land prices are going through the roof, it is hard to own a farm.”

I asked Ethan to explain some of the differences and similarities between his Mennonite sect, which allowed him to speak to me, and those that would not.

“The Amish are more restrictive in their interpretation of what it takes to live the New Testament life,” Ethan explained. “What we agree on is that it is important to raise our children, not just let them grow up. We are fully accountable for what they learn and do.” Children are either home schooled or attend Amish or Mennonite schools, but do not got to public school. Furthermore, no women work at Ethan’s shop, and he told me that he does not believe women work at any of the other cottage shops either. Married women with children are deemed homemakers in that community.

“I went through tenth grade, left school at the age of 16, started working in my father’s furniture company, the Kenton Chair Shop, and have been here ever since. Leaving school at that age is not unusual for plain people. I went to a private school that sheltered me from a lot of outside influences. I grew up with no TV or radio. The curriculum was largely Bible-based. The school only went to tenth grade, but many of us go only to eighth grade, which is the legal minimum.

“Both Amish and Mennonite agree the Old and New Testaments are inspired by God. We see ourselves as living in the era defined by the New Testament and created in the image of God. Why we limit ourselves goes back to a long-range view about where you want to end up when life is over. I would invite other people to ask that question, as we do, not just about their woodworking but their lives as well.

“In the end, only the best is going to endure. Whether you are talking about finishes, chairs or religion, only the best endures. For us, that is not just a saying. It is what we believe and live.”