Readers of the Woodworker’s Journal print magazine over the years likely recall seeing, every so often, a project done with stunning detail in the style of Arts and Crafts era masters Greene and Greene. The woodworking genius behind the vast majority of these projects was Mike McGlynn, an irreverent, supremely talented, mile-a-minute talker of a man.

It was a loss not just to Woodworker’s Journal but to the world of woodworking as a whole when Mike, aged only in his 40s, passed away earlier this year after a fall suffered while pursuing his hobby of rock climbing.

A native of Wisconsin, Mike learned woodworking from his father, a veterinarian who pursued it as a hobby. Mike grew up in the area that was the early twentieth century home of Frank Lloyd Wright, but he refused to adapt Lloyd Wright as his design hero because of his lack of admiration for some less-than-stellar personal qualities of the famed man, which were well remembered in that area. (Mike would have phrased his opinion much more colorfully.)

Mike kept at woodworking beyond his boyhood because he found it fun. “At the very base of it, I just like to make things,” he once said. “I like to take new lumber and turn it into a nice, aesthetically pleasing piece.

“Chairs in particular are very satisfying,” he said. “It can get quite complex … making them aesthetically pleasing and still structurally solid. It’s a real challenge.”

Mike’s college degree was in political science, but his career path followed the areas you’d expect of a woodworker: things like cabinetry and building boats. He eventually launched his own shop, McGlynn Woodworking, and eventually moved to a furniture concentration.

He came to concentrate on the Prairie School and Arts and Crafts styles, because their linear aspects and solidity appealed to him. He looked beyond the most-used names in these styles, those of Frank Lloyd Wright and Gustav Stickley, to the many other architects and designers involved.

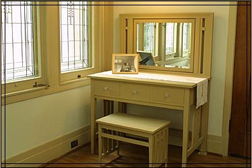

Mike developed a particular admiration for the work of Charles and Henry Greene, and for that of William Gray Purcell and George Elmslie. He made a point of touring the still-standing houses designed by the Greene brothers, such as the Gamble House and Robinson House in Pasadena, California, and used such tours as inspiration for his pieces like the Robinson Table. Mike thought Greene and Greene’s work was both “beautifully made and wonderfully engineered.”

As for Purcell and Elmslie, Mike was the woodworker commissioned to reproduce the furniture from Purcell’s personal home, working only from two photographs, after the Minneapolis Institute of Arts acquired the house.

Mike spent several years building furniture, both for clients and for Woodworker’s Journal, from his shop in northeastern Minneapolis. (Sometimes, the two customers combined our resources: some of the nicest pictures we have of Mike’s work were taken in the homes of the clients for whom he’d built the piece.)

He was also a big fan of Modernist architecture and design. “I have a really great appreciation for a clean, modern piece that is simple and aesthetically pleasing,” Mike wrote. “In some ways, this is a more difficult thing to pull off than the more traditional designs.”

A few years ago, family circumstances caused him to move to Las Vegas. He continued to make frequent visits to Minnesota and to his shop here but, during his absences, offered its use to other woodworkers in the area, like those on the Woodworker’s Journal staff. (Perhaps he overheard the not-so-quiet comments expressing envy of his mortising machine.)

While in Vegas, Mike also indulged some other, fitness-related hobbies, including swimming and working out at the gym – where one of his acquaintances was a freelancer who frequently posed questions to be published as part of Cosmopolitan magazine’s surveys. Mike, it seems, was one of the men who represented the opinions of the male gender to the readers of that publication.

As for his woodworking, Mike was becoming more and more interested in guitar building, having restored and built several over the years.

Through his articles for Woodworker’s Journal, Mike also shared his woodworking knowledge with many, many people, in nuggets of advice ranging from: “It’s a pretty elementary thing, but in order to create a square panel, you have to start out with at least one straight edge,” to his tip for preventing chip-out when tenons were pushed through a panel: “I put a tiny break, no more than 220 sandpaper, on the outside corners of the mortises, and took my time tapping the ends into place. Then I tapped the wedges in to hold the assembly together.”

But probably the most poignant quote from Mike, and the one that seems a message from his too-short life to the rest of the woodworking world, is this: “Whether you’re a custom furniture maker or a weekend woodworker: from Gustav Stickley to your uncle Bud, one thing is commonly held. Woodworking is more than simply sticks glued together. It is a way of shaping the world around us. So enjoy the process, build a new world and keep on making sawdust!”