Michael Puryear says his career as a woodworker “wasn’t a concrete decision; it was more of an evolution.”

Throughout his life, Michael has picked up skills in a variety of areas – ranging from when he was a child and grew up in a community full of handy people, who worked on their own houses – to over a decade as an adult in Washington, D.C., where he worked for a library and consulted books on woodworking and other creative topics. For instance, Michael said, he dabbled in jewelry for a while.

He also taught himself photography, and ended up moving to New York to launch a career as a photographer. While there, his career ended up evolving in other directions. Michael’s landlord in his New York brownstone was a plumber, with a client who needed a carpenter for the kitchen on one of his jobs. The landlord knew of Michael’s handy skills, asked him if he was interested – and, for a while, Michael ended up being a contractor specializing in brownstones.

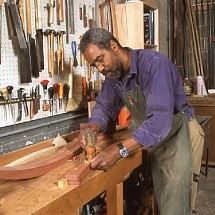

“I enjoyed the hands-on, but as I became more successful it led to more of the part I didn’t like: managing sites and losing the opportunity to do hands-on work,” he said. Some friends of his were opening a shop to build props and special effects, and they invited Michael to share their space. His first commissioned piece as a professional woodworker was from one of his brownstone clients, who asked him to make a desk.

“Once I finally decided to call myself a furniture maker, I realized the activity speaks to me,” Michael said. He also noted that, as he gained woodworking skills, he began to understand the systems. Now an associate professor of woodworking at SUNY [State University of New York] Purchase, Michael said his students will sometimes ask him how he knows something. “It’s not really the specific skill,” he explained, “but I understand the process.”

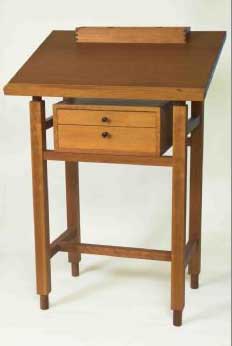

Part of his method of gaining this understanding, and teaching himself, was to give himself one “problem” with each piece he built. As an example, he cited a table he built: “Everything else on the table I could do, but I didn’t know how to do the curved bent lamination,” he said.

Michael also noted that he was at the point in his learning journey that he “really looked at it” when he became aware of such design styles as Shaker and Scandinavian Modern furniture. “I was aware of the simplicity of the form, and of appreciating the design solution,” he said. “My work flows out of that.

“It’s one of the reasons I use the word shibui [a Japanese term for “simple elegance,”]” Michael said. “It really is about trying to produce a calm,” while creating a piece that embodies simplicity but is fully functional.

In one of his latest pieces, the Dan Chair, Michael has used another Japanese technique, ukibori, to produce raised patterns in the wood on the chair legs. The technique involves putting a dent in the wood, then putting the piece on the lathe and turning it until the dent is almost gone, then steaming the wood so that it puffed back up.

This results in remaining scars being visible on the chair legs, which, in the case of the Dan Chair, “represent the scarring of the enslavement of African-Americans,” Michael said. The chair, a stylized African American chair referencing the slave tradition of late 18th century America, is built from pecan from George Washington’s Mount Vernon estate and poplar from Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello that he received from the Historical Woods of America organization. “It’s an expression of my pride in being a descendant of slaves,” he said.

Overall, in his work, Michael says he chooses his wood “more as a palette for colors.” He says he uses different tones of wood to imply floating and groundedness, with dark colors having a sense of weight and light colors having a sense of lightness. He uses these color choices to achieve the look found in many of his pieces, he said, of “an arch with some element or geometric form appearing to float above it.”

“I also think curves are emotional, rectilinear forms are more rational,” Michael said. “To bring those forms together” – as in his furniture – “produces a kind of synthesis, or rightness, that I think people respond to – maybe more psychologically than intentionally.”