When we first contacted Mike Stevens about this article and told him who we were, he wanted to make sure we had the right person. Quite a few of the woodworkers we’ve interviewed in the past have been modest about their achievements and didn’t think they merited a feature story. But Mike’s concern was more how his work fit into a woodworking magazine. You see, Mike is an artist — and a pretty edgy one at that — who happens to work in wood.

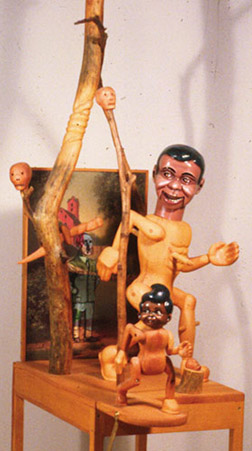

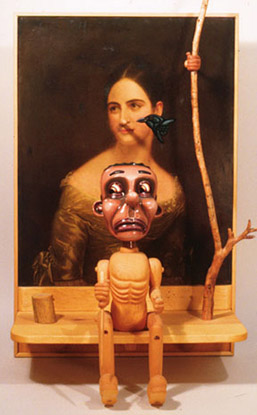

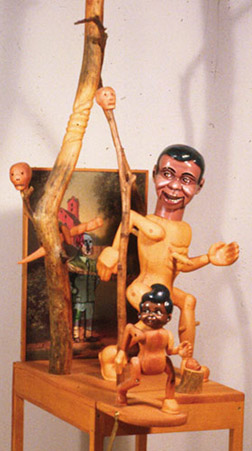

Mike’s sculptures feature a unique and personal imagery based on Disney and other cartoon characters, television, various puppets, commercial art, and “how-to-draw” manuals … most all of it remembered from Mike’s childhood in the early 1950s. He uses these seemingly innocent, and at first glance often humorous, characters to illustrate some dark and foreboding themes.

“The initial cuteness draws people in,” Mike explained, ‘but it’s like a sucker punch when they look more closely.”

Mike grew up in the Bay area of San Francisco and was always interested in drawing as a kid. One of his first experiences was winning third place in a drawing contest held by a local kiddie TV show (he won a treasury of Disney drawings). He stuck with drawing and by high school was also painting. His art teacher just happened to be Ralph Goings, who was just emerging as a super realist painter. And in junior college one of his teachers was Tony Berlant, another avant-garde artist just starting to make his name in Los Angeles.

“I was really lucky to run across these guys,” Mike recalled, “and be able to take advantage of who they were, where they were, and look at their work.”

Then in 1965, Mike started at Sacramento State College and eventually earned a Master’s Degree. While in graduate school, he worked for artist Jim Nutt, who was part of Chicago’s “Hairy Who” people … a group known for combining comics, advertising, folk art, and surrealism.

Mike’s own work was evolving: not only was he dealing with social issues like the Viet Nam war, but also he was gradually shifting from painting to sculpture. He experimented with wax over wooden armatures. Though he liked the results, he found the wax unstable, and his pieces ended up melting off the wall. Eventually discarding the wax covering all together, Mike turned to carving and painting his emerging cast of characters out of wood and setting them in miniature tableaus.

“I liked the results,” he recalled, “but it was so time-consuming to paint the carvings. It would take six months to do a piece that was only 24 inches by 18 inches. I realized I could get the results I wanted quicker by painting just parts of the pieces. So in almost all my work, the heads are painted and the bodies are left natural.”

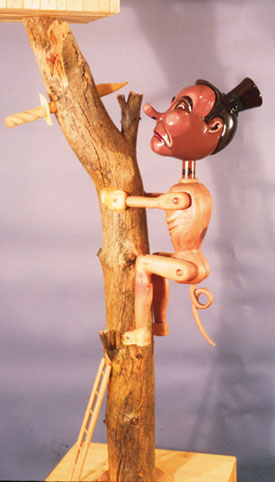

As his carving developed, his stickmen, puppets, and marionettes became more detailed and folk-art oriented. He also started incorporating tree limbs and sticks he’d find during walks in the woods. As he incorporated these elements, he’d leave some areas rough and other areas sanded smooth … which he compares to the textures he used to create on canvas.

“I just found wood to be a warm product to work with, and it fit the toys and childlike imagery into which I could work my content.”

He met his wife and fellow artist, Suzanne Adan (a painter) while in college. The couple stayed in Sacramento and, concurrently with launching his career as a sculptor, Mike began teaching high school art in 1970. Thirty-three years later, he’s still busily and passionately pursuing both careers.

“When I get done with school everyday, I come home about 3 o’clock, maybe have a cup of coffee, and go out to the studio and work three to four hours everyday, day in and day out.”

Mike carves with power tools like a Dremel rotary tool and dye-grinders. Sugar pine, which he buys from duck decoy carvers, is his favorite wood. It’s relatively soft and quick carving. A lot of Mike’s pieces are built onto tables to bring them up to eye level. Never carving against the grain, he glues on pieces of dowel or another block of wood for ears and noses.

“To get the images I want, I use un-milled wood for the limbs and laminated, milled wood for the head and body,” Mike noted. “And I love to carve heads, I just love to do it, and I’m always getting better and quicker. The head on my piece, ‘Polecat’ for instance (see the picture below), probably took six hours.”

Mike and Suzanne have exhibited together and co-manage a gallery at the high school, where the work of students is exhibited alongside professional artists. Over the years the couple has put on shows for artists they’ve met in Chicago, New York, and Florida.

Despite his commitment to teaching and helping his students get into college, Mike looks forward to retirement, when he can devote full time to his artwork. In the meantime, his work remains topical and he’s just finished “Assault on Mayberry” in response to 9/11. He admits his work can be disturbing, the way he butts innocence up against horror, but those are the stories he wants to tell in his own way.

“I grew up watching television. So drama and storytelling are the devices I’m coming from. I never had aspirations to make it big time as an artist. I was interested in just entertaining myself and showing the imagery I wanted to show. And every time I sell a piece it’s just magical,” noted Mike, “because why would somebody want to buy it? It’s just odd.”

Michael K. Stevens’ work has received numerous awards, has been displayed in scores of exhibitions, and is in numerous private and public collections. He has often served as a juror, panelist, lecturer, and curator over the years. He is represented by the Braunstein/Quay Gallery, and his work will be on display later this summer at an exhibition at the Museum of Craft and Folk Art in San Francisco.