It’s common knowledge that a good percentage of full-time furniture makers don’t like doing chairs. That’s one reason why Michael Doerr saw chair making as the perfect niche for himself. A former boat builder, Michael lives and works on the shoreline of a tiny spit of land in one of the bays off Lake Michigan.

“I was used to dealing with bringing curved members together in shipbuilding,” Michael pointed out. “On the stem, the curved structural member that forms the bow of the boat, you bring planks around from the widest point to the narrowest point and join them. There are also ribs that go from the stem up to the shear line, where the deck is attached. All of that is complex curved angle joinery, and in boat building, that’s sometimes done upside down. By the time you get to the tip of the stem at the bow, where the deck timbers, clamp, shelf, shear and ribs all come together, you have some complicated joinery. When I looked at chairs, coming from that sort of background, they didn’t look too scary to me.

“I grew up in Milwaukee, but we had a summer home where I live now, and it was surrounded by water. In 1978, after leaving college, I apprenticed to a shipwright named Ferdinand Nimphius, building huge wooden sailboats, some with 60-oot hulls. A friend who was working for Nimphius told me I should come and try it out because it was a lot of fun. He said it was like putting a puzzle together, but you were allowed to change the pieces to make them fit. I’m not too patient when it comes to puzzles, so being able to modify the pieces to fit had a lot of appeal. He was right; I liked it a lot.

“We worked out in central Wisconsin where we followed the ‘ten below zero rule.’ If it was any colder than ten below, we didn’t have to show up for work, but once it hit only ten below, we had to be there. There were areas of the shop that were heated, but the bulk of it was not, including the outhouse. The vast bulk of the work was with hand tools. Of course, in the summer it got up to 100.

“After three years with Nimphius, I went out on my own doing small wooden boats, cabinetry and furniture. Around the same time, in 1981, my wife and I bought an old stone farmhouse, gutted it and rebuilt it. The shop was in a converted hog shed. I was building furniture, built-ins and boats, and trying to figure out where I was going. At one point, my father gave me Sam Maloof’s book, and I attended a couple of his seminars at Anderson Ranch. I decided I could start making chairs, and have been doing it ever since.

“At first, I would show at outdoor art festivals, then moved to more well-known furniture shows like the Philadelphia Furniture Show and the American Craft Council shows. I’d take a small line of my designs with me, but would not change my designs for orders. The only custom part, other than adjusting chairs to the size of the person, was allowing people to choose the wood. In short, I’ll do ergonomic changes but not design changes.

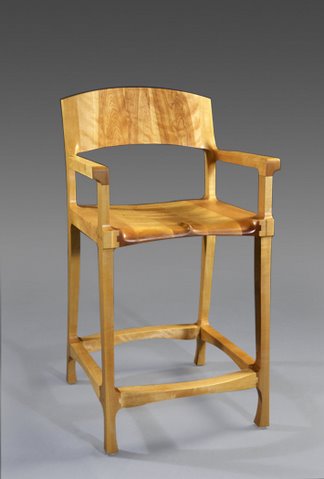

“Of course, there is a lot to choose from. I make about a dozen different chair designs, including three different rocking chairs. Tables go with chairs, so I have always done tables as well.” The chair designs all sport rather interesting names, and when I asked about them, I discovered they all had logical links to their origins.

“My all time favorite design,” Michael told me, “is ‘Bobbi’s Chair.’ Bobbi is my wife and muse. When I first made it, she really liked it, so it was named for her. ‘Celebrate’ is a design named for the period when my wife went though breast cancer and was declared in remission. The ‘New Number One’ chair is a variation of the ‘Number One’ chair, which was the very first chair I ever designed and built. ‘St. Louis’ is so named because that’s where I first showed that design.

“When I start designing a chair, I always start in profile, because that’s where most of the subtle curves show. When building a chair, I start by taking 13 flat milled boards, two inches thick. Five become the seat, two become the front legs, two become the back legs, two become the arms, and two are used to make the back. Bobbi’s chair, for instance, starts with a block about five and a half inches wide and 28 inches high.”

In spite of his boat building background and a professed ability to work with curves, Michael keeps the joinery simple by making it all square. “I do all the joinery first before I shape the parts,” he explained. “All the joinery is square, at 90 degrees. After the joinery is fitted, the pieces come back apart and are shaped separately from patterns. The key to the whole thing is that the joinery is simple, but once the parts are cut to their curves, it appears as if the joinery is complex.

“I don’t draw things in advance, so when I go to build a new design, I purposely build with larger boards. I start by scooping the seat, then shaping the back. At that point, I can sit in it and adjust the back to what is comfortable. I move it up and down, back and forth, tilt it, and so on until it is right. When it is right, I strike a pair of parallel lines on the board that will become the back legs, and fit the curves accordingly. This, in a nutshell, is the start of what I teach in my courses.

“Teaching began about eight years ago while I was describing this process to a furniture historian. He told me I had a system, and I realized it was teachable. After I showed up on the cover of a woodworking magazine, someone came to me and asked me to teach him how to build a chair. I taught him in my shop over a period of five days. After that, I decided I liked teaching and took on a few more students, one on one, in my shop. In addition, I have taught at a few of the woodworking schools around the country in classes of five to eight students, but I still teach one on one here in the shop. I only do a few of these classes each year, but while I am teaching them, I am building as well, so I do get some work done during the class.

“Along the way, I have managed to pick up some accolades for my work. I won a design award from a woodworking magazine aimed at the small woodshop owner, and the Prima award for best new product of 2006 for my torso rocking chair, whose back lines are traced from my wife’s torso. That really wasn’t a stretch, because I use human body lines for a lot of the curves in my furniture. For instance, I often get curves by tracing my own arm or leg, and modifying the basic curve to fit its task.”

Beyond building, Michael’s approach to marketing is somewhat unusual, and reflects some of his more deep-seated reasons for doing this sort of work. “I’ve given up selling furniture,” he insists. “Instead, I tell my clients, ‘If you buy a chair I will make it personally for you. When you take it into your home, you will not only have functional art, but also the touch of a human hand in your home.'”

“I have hand thrown pottery and glass that I use every day, and each time I use one of those pieces, I am communing with that artist through the artifact. To me, that is the connection to the craft tradition, and also our connection to the future. When you present your work, it is part of how you present yourself. The body of work you create is who you are.”

Three years ago, Michael added another dimension to his body of work, taking the plunge into philanthropy on a very personal level. “Because I am dyslexic, and because my daughter is also, I started a scholarship three years ago. It goes to one graduating high school student with some sort of learning disability who has gone through the special education program. It’s awarded to a student who has overcome their challenge and improved enough to make it into college.”

As for his chair building and his shop, he feels his situation couldn’t be better. “I plan to keep doing this for the rest of my life, mostly because I am having fun. I’ve built furniture from a shop where I can watch deer and eagle outdoors, be at home while my daughter was growing up, commute by walking a few yards from my house to my shop, and get to design new chairs.”

Yep, that certainly sounds idyllic to me.