The art muse came early to Michael Brolly, and came with a vengeance. “After my first day in kindergarten,” Michael recounted “I decided I wanted to be an artist. I went to Catholic school, so there was no art, but my father did almost everything with his hands, and that put the idea in my head that when you want something, you make it. At the age of eight, I made a wood chalice and a lidded ciborium by carving them from blocks of softwood, and a jewelry box using handmade trunnels. I used to carve tiki gods and sell them to my friends at school.” I imagine the nuns were none too pleased with that.

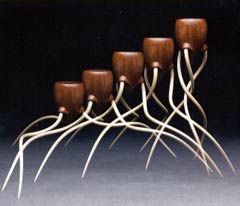

Brolly has come a long way from whittling softwood. Now, at the age of 55, and married to the granddaughter of the late, famous wood finisher George Frank, he is widely regarded as one of the best and most creative wood artists on the gallery circuit, wringing a plethora of other-worldly beings and images from wood. Many of his pieces are highly animated, strangely anthropomorphic, and just plain curious, sometimes hiding drawers, mirrors and clever devices beneath their oddly elegant exteriors.

Like most artists, he frequently supported his creativity with a much more mundane job. “After high school, I got a job in a plant that made beer cans,” Michael confessed. “I took art classes at a community college and tried to go to a university to study art, but dropped out because most of the people there had much more art training.”

At the age of 26, he overcame the intimidation and went back to the same school, Kutztown University, to try again. This time he made it, studying woodworking and art. “I took as many woodworking courses as I could, and studied with John Stolz, who was a major influence on me.” There, he met the lathe, and a love affair began that soon had him producing turnings worthy of notice.

“I graduated in 1981, and that year, met Albert LeCoff, the cofounder and executive director of The Wood Turning Center in Philadelphia.” Albert put some of Michael’s lidded boxes in the North American Turned Objects show, and again the next year at the International Turned Objects Show (ITOS). About that time, he met Stephen Hogbin, who was to have a serious influence on the impressionable Brolly. “Hogbin was taking things off the lathe, cutting them up, and putting them back together. I tried to do something like that without copying him, and decided to make my pieces walk and fly.” He’s not kidding. When you arrive at the home page of his website, two of his creations fly across the screen toward you.

From 1976 to 2004, Michael was a full-time woodworker, with occasional forays back into the beer can plant when it was necessary for monetary reasons. Though he made some standard furniture pieces, he mostly worked as a turner and artist. While much of his work is done on a lathe, you could hardly call him a simple turner, but in spite of his creativity, the road to acceptance was not that smooth. Oddly enough, words, not wood, made the difference.

From 1976 to 2004, Michael was a full-time woodworker, with occasional forays back into the beer can plant when it was necessary for monetary reasons. Though he made some standard furniture pieces, he mostly worked as a turner and artist. While much of his work is done on a lathe, you could hardly call him a simple turner, but in spite of his creativity, the road to acceptance was not that smooth. Oddly enough, words, not wood, made the difference.

“I didn’t start getting accepted into shows until I started putting weird names on my work,” he told me, “starting with ‘Mother/Daughter: Hunter/Prey,’ which was in ITOS in 1981. The strange names helped. I started getting invitations to other shows.” Clearly, it was not just the names that were strange. A later incarnation, called ‘Mother/Daughter: Hunter/Prey II’ actually looks just as good, though quite different, when posed upside-down. “Mother/Daughter helped me get discovered, and was very exciting to me personally.” Michael said. “In my mind, it was an homage to Stephen Hogbin.”

With Brolly, odd is the name of the game, and sometimes, the stories that surround his art are as convoluted as the pieces themselves. Take the case of “Thinking of my Mother-In-Law Marianne and Those Magnificent Mahogany Breasts,” a jewelry box creature whose many mahogany breasts hide a rank of drawers and whose head hides a mirror.

“That was a commissioned piece I quoted at $10,000, but found it ended up costing me twice that to make.” Anticipating the income, he took his mother to Africa, where her sister was a missionary. Clearly, the Dark Continent worked its influence, but as it turned out, the piece never made it to the customer. “After it was made, I could not find the people who ordered it,” Michael recounted. “I ended up giving it to my sister.”

One of his latest commissions, still in the works, is a Brolly guitar being made for Martin Guitar Company. Its upside-down body sports sound holes that make it look like an alien, something that would fit right into his line of curiosities. He’s even designed a production piece: a padauk and ebony Harry Potter-inspired wand being sold through Alivans, a company that bills itself as “Makers of handcrafted magic wands.” Still, when I asked him to name his favorite piece, he admitted, “It’s always the next piece.”

In spite of his skill and creative artistry, Brolly has had difficulty consistently selling his work, and he often found himself back at the beer can plant. Lately, though, he’s taken a new direction, and is in an MFA program at the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth. Once out, he intends to teach.

Listening to him, I am fully convinced he’ll be a heck of a teacher. I can just hear him passing on to his students this tidbit of advice that he shared with me:

“Believe in yourself, and swing for the fence.”