When he retired about 10 years ago from a career as a biochemistry teacher, Malcolm Zander had “no knowledge of woodturning, and no interest in it.” That has changed.

The first step in his road to woodturning came about when someone suggested he go and look at the creations of his wife’s executive assistant’s son. Woodturner Jason Russell’s work “looked interesting” to Malcolm — “it looked like fun.”

Back then, Malcolm had done well enough in the stock market that he was able to buy a lathe, wood and equipment in order to try out turning. Actually, he said, when he bought the lathe, he was told, “‘If you don’t like it, you can sell it in six months for what you paid for it.’ So there was no risk.”

Malcolm started out turning functional things like salad bowls. He started attending craft shows in order to demonstrate he was making an effort to generate income — necessary “if you asked the tax man for a deduction” – and started to become more interested in ornamental turnings. “It’s boring to do salad bowls all the time,” Malcolm said.

Instead, he happened upon his niche in woodturning “by accident.” Malcolm was in the midst of turning some natural edge vases from African blackwood, and was looking for a means of making the sapwood, which he considers an uninteresting brown color, more exciting, when he heard about a turning demonstration in Albany, New York. That’s about a five-hour drive from Malcolm’s location in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada.

“The incredible thing about the woodturning community is that everybody shares techniques. There are no secrets,” Malcolm said, and the demo by Binh Pho on piercing with a dental tool “blew my mind. I went home and bought a compressor, an air brush and a dental drill, and went to work. It evolved from there.”

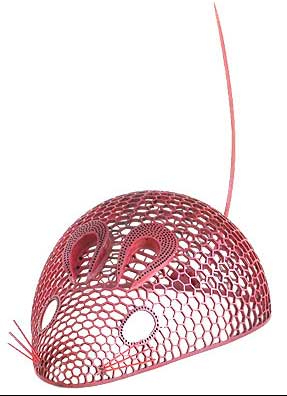

Among the directions his work evolved into was the project “Lacemouse,” which Malcolm said “was a lot of fun.” After letting his mind wander and seek inspiration, it had come to him that “it would be fun to make a mouse. It sat in my mind for two years to figure out how to make it.”

Malcolm notes that, due to his pension from teaching, “I’m very fortunate in that, unlike a number of other professional turners who have to make a living at it, I don’t. I can spend as long as I want to play around with details and try to get it right. If you’re turning to make a living, you can’t afford to do that.”

He’s able to spend time trying new things, a process he likes, “because that’s how you grow.” His latest project, for instance, was a turned teapot. “I’d never made one before. It took a month to figure out how to do it and another month to make it. It was so much fun, I’m going to make some more.”

For his projects, Malcolm frequently uses hard exotic woods like African blackwood and pink ivory. “When you’re piercing wood, it needs to be strong to take the fine detail in the fine little cuts,” he said. “It helps if the wood is pretty, too.”

Malcolm, who is originally from New Zealand, has also made a couple of items from some of that country’s unique woods. Swamp kauri, for example, is “very turnable,” Malcolm said. One piece of the certified 40,000-year-old wood he had turned was a burgundy color, while the other was green.

Unless you get the root or crotch wood of kauri, though, Malcolm said it tends to be rather grainless — and he thinks the wood from New Zealand’s’ rimu tree is much more beautiful. Part of the flora that developed during New Zealand’s long isolation from other continents, rimu is, however, a restricted wood — so turning with it is a rare occasion.

Not so rare these days is Malcolm’s participation and interest in the woodturning world. Before picking up the post-retirement activity, he had dabbled in woodworking by making simple things like cheeseboards. Today, in addition to producing all of his own turnings, he serves on the board of the American Association of Woodturners. “In 10 years, I’ve come a long way,” he said.