Turning a bowl from kiln-dried wood is problematic due to the sparse availability of 4″ or thicker planks needed for a decent bowl. And if you do find some, expect to pay $14 or more a board foot. That’s why most turners turn green wood from blanks they chainsaw from freshly fallen logs. Historically, this was the way bowls were turned, so I don’t think our ancestors thought anything of a bowl being oval. That was the way it was supposed to look!

Many turners, myself included, keep the tradition alive by turning green wood bowls to final dimension and allowing them to warp oval. If this bothers you, it is only slightly more work to leave your bowl a bit thicker initially and allow it to dry for about three months. You then re-chuck your dried blank and make it round with a normal wall thickness in a second turning session.

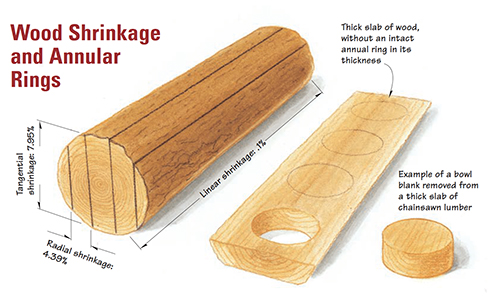

As shown in the Drawing, a log does not shrink very much along the grain: only 0.1%. However, it shrinks up to 8% tangentially along the annular rings, and slightly more than 4% in the radial plane, which is at right angle to the annular rings. If left as a log, cracks (called checks by lumbermen), will soon appear. The nature of these cracks depends on the wood. One huge crack can appear in a wood like pine, while elm or beech will have a myriad of small cracks, as in the photo at right. The lumber industry deals with this by cutting logs into boards that do not have a complete annular ring. Think of it as the cardinal rule of the cardinal rules: leave no complete annular ring in your bowl blanks.

To do this, I will crosscut a section of log slightly shorter than my chainsaw bar — this is called “bucking” by tree cutters. Support this log on a cradle, which you can nail up from construction material or improvise from short sections of logs. Next, I’ll rip boards from the log section, after first ensuring that my chain is very sharp!

I rip down the middle first, but do not cut all the way through. I stop about 1″ to 2″ shy of the bottom. For a small log, I make a center rip, trying to cut through the center or pith of the tree. More specifically, for larger logs, I make two rips, one to each side of the center so as to completely eliminate the center of the log. I stop both cuts 1″ to 2″ shy of completion. Next, I rip planks of the desired thickness to either side of the center cut or cuts. On a smaller log, I will get two planks, but on a larger log I can get four or six planks. On larger logs, I work from the outside to the center.

I do enough of this type of work that I have a very powerful chainsaw: 70cc with a 25″ bar, what the manufacturer, Stihl, catalogues as “a saw for extraordinary cutting needs.” I can get two good-size bowls out of each plank I rip with this saw. The average home or farm duty saw will typically have a 12″ to 18″ bar so you will more likely yield one bowl per plank.

After ripping the planks from my log, the next chore is to band saw a circle to create a blank. It’s straightforward, but you need a coarse blade. I use a wide, four-tooth, skip pattern that cuts very aggressively. You must now turn your freshly cut blank before it dries or store it in such a way that it will not dry out.

This brings a second caveat to wood drying — the elastic limit of the material. If I bend a thin strip of wood, it will bend a good deal before breaking. A thicker strip will not bend nearly as much. I’m dealing with very thick planks here, and they will almost certainly check during drying if left as is. But if I turn a freshly minted blank to a bowl with a reasonably thin wall, the wood will be able to bend much more readily as it dries. A good rule of thumb is the wall needs to be 10% of the bowl diameter, or less. This means that a 10″ bowl needs a 1″ wall to survive drying. If you want to turn your bowl a second time after drying oval to achieve a round vessel, 10% gives sufficient wall thickness to do so.

If you want round bowls, turn your blank to a 10% wall thickness and let it dry for about three months. Wrapping it in several sheets of newspaper, or a brown paper bag, for the first month further reduces checking because the end grain loses water faster than the plank grain. The paper creates a sufficient vapor barrier to equalize this. If tomorrow is someone’s birthday, you can dry the wood rapidly in a microwave. Directions abound on the Internet for microwave drying — but I just wait three months. I have a big pile of blanks drying — handy.

More often than not, I simply turn the bowl to a pleasing wall thickness. I then sand it and apply an oil or an epoxy finish. The finish creates a vapor barrier and does the same thing as newspaper. The bowl dries oval over the succeeding week, but it is just as useful as its round cousin.

Chainsaw Safety

VIDEO: Cutting Bowl Blanks Safely with a Chain Saw

1. Never use a chainsaw lefthanded. It is a right-handed tool only.

2. A chainsaw is only to be used by one person at a time. All observers should stay a good distance away.

3. Never use a chainsaw alone.

4. Never use a chainsaw above your shoulders or on a ladder.

5. Always ensure that the chain is tight before starting work and check it frequently.

6. Make sure your chain is sharp — a dull chain is more prone to accidents.

7. Always cut at a high throttle setting. Cutting at partial throttle is more prone to kickback.

8. Use a ground start or a knee start — never a cowboy start.