Lynne Buss got an education in manufacturing and then spent nearly five years working as a mechanical engineer. And then, she decided to try to find a job that used her hands and let her work from home.

Back in her high school days, aptitude tests had indicated that she was equally suited for artistic and technical pursuits. “The technical world requires artistic abilities, and the artistic world requires technical abilities, but I was trying to find something to suit both,” she said. She settled on marquetry. “The technical aspect of it attracted me and also the tangibility. It suited me really well,” she said.

During her childhood, Lynne had seen a marquetry scene her grandparents brought back from Venice that inspired her. Her inlaws’ home was also filled with such images: her husband’s grandfather had worked as a marqueter.

Lynne started out her own woodworking career, about 26 years ago, using the grandfather’s tools, including a “tiny” scroll saw.

Back then, it was a challenge to find the woods she wanted to create her images, since there was no such thing as Internet shopping, and the appearance could vary so much from log to log. “I’d have to call and say, ‘I’m looking for walnut, and burled, and highly figured…'” she explained. She does not use dyes, stains, or fillers in her pieces, which are all created from veneers. Nowadays, Lynne can go online and look for specific pieces of specific types of wood, of specific colors.

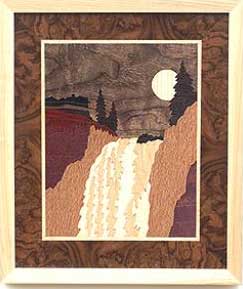

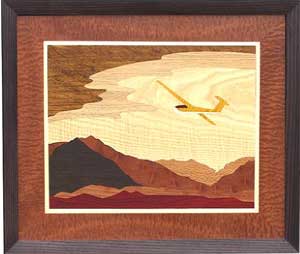

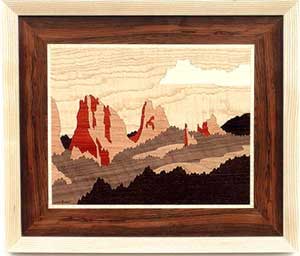

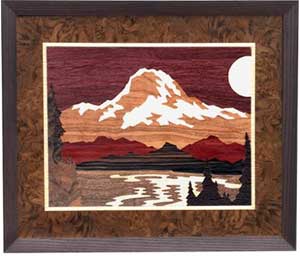

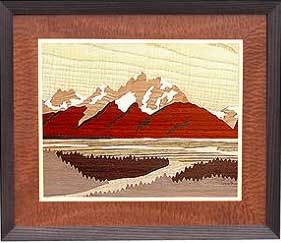

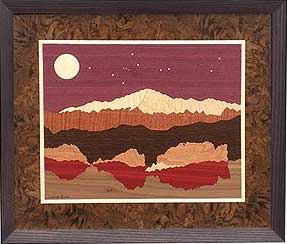

Lynne aims for marquetry scenes with a contrast between light and dark woods, although she admits having a personal preference for darker woods. “They’re more interesting, more highly figured,” she said. “There’s a lot of bland woods out there, and I don’t like those. It doesn’t make for a nice scene because I don’t have the color contrast.”

Lynne’s usual process is to stack and cut the woods for her images, which helps when she puts the scenes together. “If one’s lying right next to each other [when she cuts them[, it’s’ a better fit,” she said. Highly figured woods, while attractive, unfortunately don’t always lie flat for this process, she said. “And rosewood is difficult to glue because it’s so resinous; I have to treat the back with rubbing alcohol before I glue.”

Even with fluctuations in wood supply – “sometimes it’s harder to find maybe lacewood, or bright white English sycamore for a while, and then it will come back” – she does try to use similar woods throughout her work. “So if somebody wants to buy, say, three pieces, they go well together,” she said.

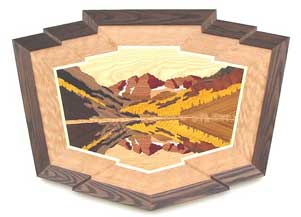

Saleability has also influenced the topics of her scenes, which are currently all landscapes. (She has tried other subjects, such as animals, in the past, but they just didn’t sell as well, she said.) All of the landscapes, in turn, are based on real landscapes – predominantly areas where her family has lived, such as their current Colorado abode, or the Washington and Oregon areas of the Northwest from their previous residence.

“I start with a line drawing created from photo, and I’ve sometimes added my own artistic license,” she said. “I look at it as a silhouette.” When she’s creating, for example, a mountain scene, Lynne said, the mountains in the back of the image are a little lighter in color, and they get progressively darker as the image moves forward.

Lynne’s landscapes incorporate both day and night scenes. For the nighttime visions, she has a computer program that allows her to input real star patterns. She creates the intarsia constellations with brass disks she’s punched out of sheeting.

She also makes panorama scenes, which is her current favorite project to work on. “It’s a larger project, and the frame is stepped, more shaped – I do the framing and enjoy that part of woodworking as well,” Lynne said. “I prefer doing a bigger project. My scroll saw only has a 16″ throat, so to cut larger pieces is more of a challenge, and more rewarding as well.”