When he turned 35, Konstantinos Pilarinos recognized that though he was a talented woodcarver, he was but one of many in his native Greece. To make a better life for his family, he decided to follow in the footsteps of countless determined people before him and come to America. And the fact that there weren’t many woodcarvers meant he could make a mark in the new world.

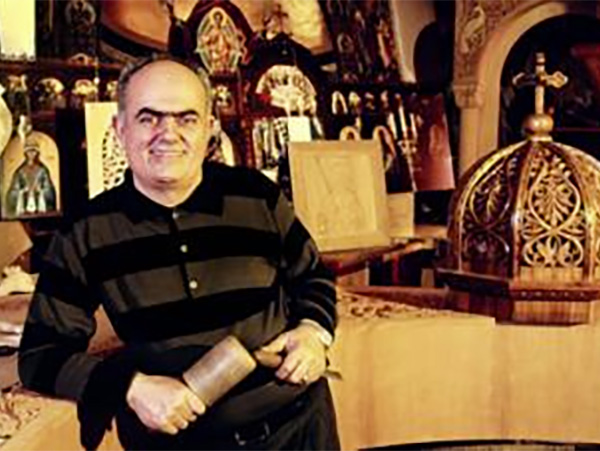

Twenty-five years later, in the year 2000, the National Endowment for the Arts recognized Konstantinos with a National Heritage Fellowship. The award honors masters of folk and traditional arts and proclaimed him “among the world’s dozen masters of Byzantine icon woodcarving.”

How did he move from immigrant to master? And what’s a Byzantine icon? The answers to the second question will help explain the first.

Byzantine icon woodcarving is a tradition dating back to the fourth century. When the eastern Christian Church broke away from Rome, it developed a unique form of religious art — the icon – that portrayed people not as they appear, but as transfigured by the power of God. Inside these Orthodox churches, especially those in Greece, the icons were incorporated into an Iconostasis … an elaborately carved screen that separated the sanctuary or altar area from the nave where the faithful assembled.

Konstantinos’ life became linked to icon carving at the age of thirteen. His father had just died and since his mother couldn’t afford to keep him, she sent him to an orphanage.

(Though he speaks good English, Konstantinos was more comfortable having his daughter Penny talk with us over the phone.)

“He went to visit his uncle who was a chairman of the orphanage,” Penny explained, “The uncle had a beautiful hand-carved table in his house and asked my father if he’d be interested in doing something like that.”

Indeed, he was interested and an apprenticeship to a master woodcarver was arranged. By the time he turned 18, he owned his own shop. His ambitions eventually brought him to our shores. With few skilled carvers in America, the Orthodox churches — Greek, Russian, and Ukrainian — hailed Konstantinos’ arrival as a godsend. Today, he’s a American citizen with over 60 Iconostasis completed, and he is the proud owner of Byzantion Woodworking Company in the borough of Queens, New York.

To begin a project, he visits the church and measures the space.

“Sometimes the church has definite ideas about what they want in each panel, while some just say they want a screen. The painted icons will come after his screen is installed,” Penny observed, “We show them examples of past work and then we do a sketch of what we envision.”

When he gets back to his shop, he’ll create stencils from Penny’s detailed drawing or reuse one of hundreds he’s accumulated over the years. The stencil is attached to the wood, and he then uses a drill and jigsaw to cut out the basic design. Then he goes to work with his chisels. No power tools can be used because the work is too intricate. The woods he prefers to use are basswood and mahogany, but he’ll also use oak and maple. (According to Penny, he does a wonderful bleached oak that looks just like marble.) He doesn’t bother to smooth or plane the surface, since he’ll be carving every square inch.

Striking, beautiful images will eventually flow throughout the screen.

“Everything he carves is symbolic,” observed Penny, “One of his favorite themes is the grapevine. The vine represents our religion and how it’s growing, and the grapes represent the faithful and their belief in God. To represent the power of God, he’ll often incorporate a double-headed eagle on the panels underneath the icon. Sometimes he includes a dove to personify the Holy Spirit or peacocks to signify eternity. And even though he may include the same symbolic forms, each piece is unique.”

Each screen is made up of many pieces that must fit together into a sound structure when reassembled in the church. To make the project even more challenging, Konstantinos is also usually involved with designing the entire interior of churches, creating pulpit stands, bishop’s thrones, chanters’ pews, and the other furnishings that come with it. He even finds time to do some work for private homes.

Like the master who trained him, Konstantinos brings apprentices into his shop. Interestingly, he likes to work with woodcarvers from South America. As Penny explained it, they’ve learned the Baroque style of woodcarving before they arrive. He trains them in Byzantine style, which is more dense, elaborate, and intricate. Of those who can make the transition, some stay on as employees; others may eventually open their own shops. But without the religious connection, Konstantinos doesn’t think they can really follow through on the style.

The strength of his own faith and pride in his Greek background has made him and his work part of every Greek community in the U.S and Canada. In addition to churches, his work has been exhibited at the New York State Museum and the Museum of American Folk Art, and has received numerous awards. At the moment, he’s working on a Russian Orthodox Church in Florida. Does he ever relax?

“He goes to Greece and studies the work in the old churches,” Penny explained, “In many ways he’s already left a mark and fulfilled his mission. But he never wants to retire.”

What advice does he have for someone just starting out as a woodcarver? It’s a beautiful art, but you have to have a lot of patience. It takes years and years to become a master, and you really have to love it to do it. But the love shows through your work.

(Photo by Tom Pich – https://www.arts.gov/honors/heritage/fellows/konstantinos-pilarinos)