Kimberly Winkle has always been interested in structural architecture, the way things fit together. As a child, she cites the influence of her babysitter – a local art teacher – in inspiring her to experiment with various materials in her parents’ garage, trying to make birdhouses and such.

She translated her interest into a college degree in ceramics – with a focus on large, sculptural pieces. Clay, however, “has limitations structurally,” she said, and when she took a woodworking class during her second semester as a ceramics graduate student at San Diego State University, “it was just a natural fit.”

Welcomed by program head Wendy Maruyama, Kim switched over to the woodworking program, supplemented her education with workshops at places like Penland School of Crafts, Haystack Mountain School of Crafts and Anderson Ranch Arts Center, and began making furniture and forms from wood.

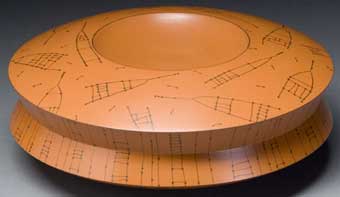

For the past year or so, she’s been focusing on lathe-turned tables. She sells a line of them through the Artful Home and chose tables in part because she was looking for something that was “marketable in terms of both aesthetics and time. It’s a fun object that’s not too large to ship and doesn’t take too long to make” –and thus drive the price up. Also, she had some 8/4 mahogany that was only 19″ in length and was “trying to figure out what I can make with the mahogany.”

The first pair of tables in this series were her Tit for Tat End Tables, which Kim describes as a “clever duo” with “yin and yang”: areas that are painted on one table are not on the other, and vice versa. “I just think that they’re kind of fun that way,” she said.

When she paints her items, Kim said she prefers to primarily use milk paint. While color – along with form and line – is one of the three main areas of her focus, and she does describe her color choices as bold, she also notes that her choices are “not fast car red and not obnoxious.”

“If I’m going to be painting something, I’ll generally use poplar,” Kim said of her wood choices. “It grows so abundantly so many places in our country. Also, poplar, in my opinion, is not too visually exciting. If I’m letting the natural wood show, I generally prefer warmer wood, like cherry or mahogany.”

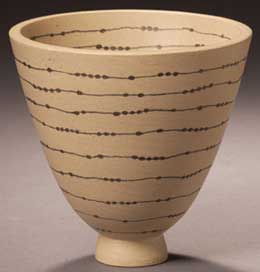

She’s also interested in making marks on her pieces, “a combination of furniture making and drawing,” as she put it. Her preferred marks are also a combination, of lines and dots. “Put together and combined, they make each other stronger,” she said. “It’s like a visual Morse code as repetitions occur. The spacing and form of things creates a sort of code, although there is no actual message.”

As she creates her items, Kim notes that her experience with ceramics has definitely had an influence. Her knowledge of the history of vessels, for instance, has “informed my woodturning – the relationship with the opening of the bowl to the foot of the bowl.”

And although she has not combined her ceramics work with her woodworking yet, Kim has combined additional material with her woodworking, such as hand-forged steel for castings to hold the wheels on a large mirror that slides along the wall. She traded a wooden box to the blacksmith who forged the casters.

Her latest work is a pair of turned coat hangers inspired by a visit to the restored Shaker village of South Union in Kentucky. The hangers were fashioned for the American Association of Woodturners’ show “Be Our Guest: A Progressive Invitational,” a show Kim was invited to join at the behest of turner Merryll Saylan. She likes them, Kim said, because they allow her to mentally revisit South Union – and also because they are “a surprise.”