“I like to take serious things lightly, and light things seriously.”

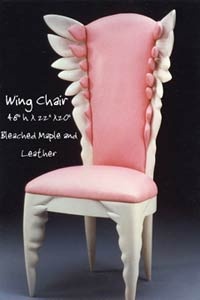

Those words, taken from Kim Kelzer’s web site, do a good job of describing this enigmatic woodworker. Her pieces, everything from kitschy lamps to full kitchens, are anything but mundane and, true to her words, present furniture in a seriously lighthearted manner. With fantastic carving, upholstery, and outrageous paint treatments, she makes whimsical furniture that can just as easily be called art.

Delve into her background, and her flamboyant style and artistic flair starts to make sense. “I put myself through art school at San Jose State University by working as a cake decorator,” Kim told me. “Prior to that I had been a seamstress.” Many of her decorated and carved pieces betray that past and, judging by them, I would have loved to have seen some of her cakes.

“I did not have assumptions about how woodworking is supposed to be done,” she explained. ” When I was in grad school, there were two other guys in the department. One thought it was funny that I would paint wood pink, and the other was appalled. I felt really inferior because I did not know the names of the tools, and did not have a background in woodworking. However, I did know how to paint and sew, so upholstery and finishing did not scare me.”

She points out that it makes sense to bring everything you know into woodworking, even things that don’t seem applicable. “When you go about the best way to use wood, I see it as the same sort of decision making you use in laying out a pattern for sewing. In the end, it helps not to have preconceived notions about what you are supposed to do.”

There was some woodworking in her past, though it, too, was hard-won. “My sister and I were the first girls to take woodshop in school. My real incentive was to piss off my father and get surrounded by boys. I distinctly remember an argument with my father where he was insisting I take typing instead of woodshop. My parents only sent my brother to college. They felt girls would only get married, and there was no point in sending them to college.”

Instead, she went on her own. “I was always good at making things and at art. I bought a table saw after high school, but didn’t get into woodworking until after I had graduated from college.” Though she graduated with a degree in painting, she says she never painted a canvas again. Instead, her painting skills show up on her woodworking.

“The local woodworkers still think I am wrecking things because I paint them. If I only had to make brown stuff, I would go nuts. It is my least favorite color. Even the Egyptians painted wood.”

Her path from art to furniture making was a somewhat convoluted one. She took furniture making classes with Michael Cooper at DeAnza College in California, and had him agree to fail her, or give her an incomplete, so that she could spend more time learning from him. He finally suggested that if she was serious, she should move to Massachusetts and study there.

She was ready. By that time, she had been decorating cakes for ten years, and was sick of it. She quit her job and moved east, eventually getting a MFA in fine woodworking from Southeast Massachusetts University, where she studied with Jere Osgood and Alphonse Mattia.

“While at school, I worked in a Shaker furniture shop. I spent a lot of time sanding, but it balanced all the design education. I got to handle a lot of woodworking tools. This was all practical, while school was artistic. I suspect each resented that I was involved with the other.”

“I wrote my master’s thesis about the influence of TV, Barbie, cars, and the Formica covered crap I grew up with on furniture. It was called: ‘Fins, Funk, and Fetishes; Influences on Furniture.'”

These days, she lives on Whidbey Island in Washington, and makes what can only be described as functional art. Her pieces are very well-made, and eminently usable, but their main calling card is that they are an expression of her. A good example is ‘Home on the Range Oven,’ a jewelry box replete with hidden compartments. It is one of her favorite pieces, not only because it is interesting, but also because it was a technical challenge. The box is curved in two directions, and there is not a square corner on it. “I liked the challenge,” she said, “but am not into making my life miserable, so I don’t do a lot of that.”

What she does is certainly well received. Her work has garnered a slew of awards and honors, appeared in more than a dozen publications, and been displayed in well over a hundred shows and galleries. Some of her pieces reside in collections situated all over the country.

For the past three years, in addition to making furniture, she has been building a home on the island. Much of it is made from found and reclaimed material, like old growth fir taken from torn down Seattle homes. “In the kitchen, for example, no two surfaces or cabinets will be alike, yet it will be functional and practical. I’ll build a really nice house for next to nothing, and that appeals to me to make something of nothing. I really do like the idea of recycling, and of using old growth forest without depleting it.”

Ironically, the house will be rented out once it is done, so part of her task will be to find just the right person to appreciate living in a work of art.

“I try to make things unique. I never understand people who try to make something they have a picture of. If you are going to go to all the trouble of making something, you ought to make something unique. One woman came to me asking that I make a bunch of Mission furniture. I told her she could buy it cheaper at an antique store, and should. As far as I know, she did, and I presume she is quite happy with that decision.”

“I make things with me in mind. I do get commissions once in a while, and will take them only if they coincide with what I want to do. I am content to make a small amount of money and make only what I want, instead of making a lot of money and making what others want. The best thing about what I do is that I don’t consider it a real job.”

“When I teach, I always say ‘This is a stupid way to make a living. Only do this if you would do it anyway in your spare time.’ I spend my time puttering in the shop, and isn’t that the ultimate retirement dream? I get to do it as a living, and have been for two decades.”