While Katie Hudnall doesn’t use a lot of jigs in her own woodworking – just a few that she turns to time and again – “I admire people who do work that way, and I’m fascinated by them.”

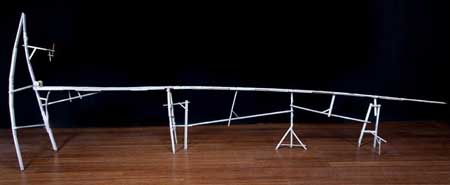

In fact, one of her favorite pieces of her own work, the “World’s Longest Drawing Table,” is somewhat of an homage to jigs: it’s 10 feet long when compressed, 18 feet long when extended, with a 3-inch writing surface. It’s almost as if, Katie said, that the table itself is “a very silly jig.”

Katie’s interest in woodworking (jigs and otherwise) dates back only a few years ago, to a class she took at the Corcoran College of Art and Design in Washington, D.C., while studying to be a sculpture maker. With that basic woodworking class for sculptors, she said, “I realized wood as a material had all the properties I was interested in, and I fell in love with it.”

Clay, she had found too soft for her tastes; metal, too hard – and neither material came with a history. “The thing I respond to in wood is the history, not only in the growth of the tree it came from – the knots, the growth rings – but also the kerf marks from being milled, the dings and scratches.”

That’s one reason she likes to use found woods – found in a variety of places, ranging from pallet woods to lumber discarded in dumpsters. In her home base of Richmond, Virginia, for example, she has found what she called some gorgeous old pine lath stays in the dumpsters near remodels of old Richmond buildings.

Richmond history has influenced Katie’s choice of construction methods, too. Shortly after completing graduate school, she moved to a farm approximately an hour outside the city. The farm had been in her partner’s family for nearly seven generations, and was full of outbuildings put together with timber frame, pole barn, or board and batten construction.

“They were all built using the vernacular of that area, and the simplest way you could think of to put wood together,” Katie said. “Nowadays, I do a lot of those construction methods, a lot of work with slats.”

Sometimes, people looking at her work in a gallery might not know what they’re responding to, but “They’ll say, ‘that shape reminds me of something in my grandfather’s shop,’ or ‘the doors in my old house were built like that.’”

Katie prefers straightforward construction methods like joinery accomplished with screws and dowels. “People can say, ‘This is put together with screws. I can see the screw.’ There’s something interesting in the lack of mystery.”

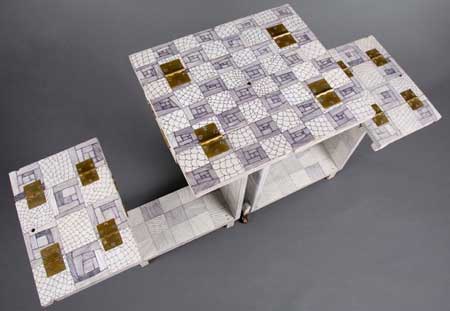

That is not to say that there is never anything hidden in her work. Another of her favorite pieces, for example, is “Pirate Stool.” It’s a traditional stool with an upholstered top – except that one of the legs is a peg leg. The peg leg comes off the stool, there’s a key stored on one of the other legs, and the top of the stool opens with the key to reveal two more peg legs, allowing the owner to “dress the stool up or down.

“It’s 100 percent me: goofy and fun. It makes people laugh a little bit.”

Overall, though, Katie wants her work to be seen. She studied under Bill Hammersley at Virginia Commonwealth University, who she cites as producing beautiful work – and beautiful jigs, that sometimes take him months to make. “In the end, people never know you spent all that time making a jig to make the piece, and they never get to see it. That’s kind of sad.”

In her own work, accomplished largely with a drill press, band saw, Japanese hand saw and chisels, Katie said, “For the most part, I’m very interested in building. The thought of stopping and building something that won’t get seen by somebody is infuriating.”

This past year in her woodworking, on the other hand, has been “really cool.” After four years of working full-time in cabinet shops, Katie finished up an artist’s residency at the University of Wisconsin at Madison in December and will begin another at Anderson Ranch Arts Center in Colorado in February. Finally, she says, she’s been able to move her full-time concentration to her own work. “It’s been a fun year for me.”