Sometimes you hear the strangest stories of why people got into woodworking. Take, for example, the case of John Thoe, a European trained carver and woodworker who just barely missed heading down an entirely different path.

“I was an exchange student during high school in Norway,” John recounted, “and I noticed the large number of girls in class knitting during lectures. It looked like fun, so I asked my sponsor about learning to knit. She suggested I learn woodcarving instead. I took her advice, and learned rococo style carving by taking 40 weeks of acanthus carving lessons from a local carver after the school day.

“That carving style is well represented in just about every village. Norway has a population of only two million, and the high number of trained carvers, many trained in school, means there are more carvers than there is demand. It’s kind of ironic but, because of that, there are virtually no professional carvers working there.

“Back in the States, I went into the army, where I became a skydiver. We traveled around the U.S. putting on air shows to recruit soldiers. When I left the service, I returned to college in Iowa and made money doing carving for furniture makers. After graduating with a BFA in sculpture, I went back to Europe, studying both in Germany and again in Norway.

“After a year, I returned to Iowa and joined a cooperative shop in which I learned to build furniture. I also did carving for the Amana Colonies furniture makers. It was there that someone suggested I would have a hard time making a living only as carver, even here in the U.S. Though I have switched mostly to furniture, I still do three or four carving jobs a year.

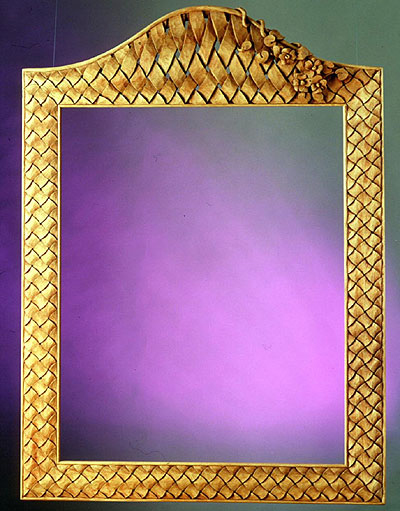

They can range from ornately carved mirrors, like the floral basket mirror and the rococo mirror, to in-the-round carved items like newel post toppers.

“After about five years with the cooperative, my wife and I moved to Seattle because we thought I’d have a better chance selling custom furniture here. I happened to stop into the NW Fine Woodworking Gallery, a cooperative gallery renowned in the Pacific Northwest. They told me of a local shop that was looking for a carver. I contacted the shop, was hired, and spent the next four months working on a major restoration project.

“In 1988, I opened my own shop in Seattle, a cooperative formed with three other woodworkers. About that time, the NW Fine Woodworking Gallery contacted me and asked if I would be interested in buying the design rights to two chair designs from one of their members. I did, and started to build and sell them through the gallery. I soon became a member. In 1999, I went out on my own after buying a house that had room to hold my shop. It’s where I still am today.

“In addition to the two chair designs I bought, I’ve designed other chairs, bar stools, tables, mirrors, frames and household items. In my chair designs, I attempt to mimic the forms in nature.

For example, the bracing and the angles I use to attach my bar stool’s legs to its sculpted seat resemble the splayed legs and tendons seen in the cat family, or in a praying mantis. They are beautifully positioned for stability. The chair frame and legs gain strength from the feather-jointed corner blocks in the frame. Each corner block consists of up to 36 inches of linear glue surface in up to six rows of tongue and groove joinery. The strength provided by these corner blocks eliminates the need for rungs between the legs.

“My sumo coffee table, which gets its name from its bowed legs, sports a trompe l’oeil wooden wallet ‘sitting’ on the top, permanently. Like most of my favorite work, it involves lots of curves. One of the reasons I prefer curves in furniture is that there is only one straight line, but an endless number of curves. Perhaps it is a throwback to my carving training, but to me, complex curves are aesthetically pleasing. The quarter sphere table is a good example of that. Tables seem rather limited, so to make something that varies substantially from the norm, you really have to design outside the box. This two-legged entrance table puts a very different twist on the simple wall table by basing the general shape on part of a sphere.

“I’ve also made changes to both the designs and the construction methods of the two designs I purchased. In my opinion, the modifications that I made to the Linnea represent some of my best design work. Last year I came out with a sculpted version of the fan chair, the other purchased design. The original version of that chair took 17 hours to make and used 155 separate setups. It is extremely complex to build. That fact makes it impractical for anyone else to steal the design and make it cost effectively. Over the years, I have crafted thousands of chairs, and have simplified the manufacturing processes along the way.”

He may have missed the boat as far as knitting goes, but it is clear from talking to John that he is completely content with the path he chose. “Even as a college student carving for furniture shops to make money,” John told me, “I knew I did not want to spend my life behind a desk. Because I love my work, I don’t expect to ever retire. I plan to be doing this the rest of my life.”

I, for one, am glad to hear that. After all, we can never have too many top-notch woodworkers.