Sometimes, the path to becoming a woodworker can take some surprising turns. John Sterling started out working in his family’s beer distributorship, and ended up working in a woodworking business that has also become a family endeavor. While he may have followed that path anyway, a tragedy along the way helped him solidify his values, and led him to do a lot more for others than simply offer them finely made furniture. I’ll let him tell the story.

“I took shop class in eighth grade,” John recounted, “and I remember one of the first projects we made using a band saw. During that project, my shop teacher said to me that I had a keen eye for grain orientation. I didn’t understand what he meant at the time, but I remembered the good feeling his words gave me, and the fact that the piece looked right to me.

“After getting a degree in marketing from Penn State, I ran my family’s retail beer distribution business. However, from the early 1990s on, I also did woodworking. I would make the occasional piece for my house, mostly shelves and the like, using a router, a jigsaw and pine boards. Eventually, I started making things for others.

“In 2002, my wife was pregnant, and I was burned out both with the retail business and with working for my family. I decided to pursue woodworking, making my avocation my vocation. That, of course, meant building a shop. A friend of mine designed a shop, and we commenced building it on our property.

“During the time we were building the shop, my son was born. Four months later he was diagnosed with a brain tumor, and he died fourteen months after that. It’s difficult to explain the impact that had on me, but it made me understand the importance of family connections. The connections you make with your family on a daily basis should not be taken for granted.

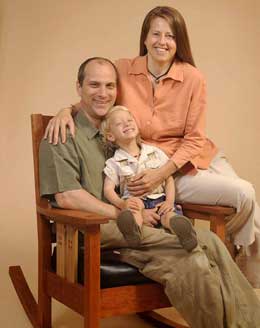

“Although I had already decided to start working from a home-based shop, this confirmed my intentions. We later had another son, and I remain committed to being home for him. My wife feels the same way, and left her job in 2005 to be part of what is now our family woodworking business.

“For a year during our first son’s illness, we moved to Tennessee so he could be treated at St. Jude’s. Fortunately, we had both the resources and the support from family and community to do that. However, not everyone is that lucky, and for that reason, we started a nonprofit organization called The Blue Butterfly Fund in honor of our lost son. Its mission is to take some of the peripheral pressures off and allow a family to focus on the care of their child. The nonprofit provides funds to assist families with the cost of travel, non-covered medical fees and general living expenses that are often sacrificed by a family whose child has cancer. The name comes from the fact that butterflies are a universal symbol of hope, and blue is the color of healing.”

As for John’s furniture designs, they flow from a number of influences. “The Pacifica sideboard, for example, has its roots in Arts and Crafts,” John explained. “I’ve taken a basic Stickley piece and lightened it up a bit. The top is thinner looking, in part due to a chamfer underneath, and the legs taper upwards to a more delicate dimension. I wanted it to still fit and belong in a period bungalow, but have its own unique look. A similar piece, the Luminaria writing desk, is a simple Mackintosh design with glass panels making up the ornamental pattern on the face.

“My neighbor is a sawyer with a portable band mill, and that’s been a source for inspiration. The Re-Su Cabinet is the result of finding a stunning walnut crotch. I took three sequential slices and separated them with vertical posts and a small cabinet. The combination created both a table and a storage cabinet.

“The slab for the Shibui table had a huge bark inclusion. I removed the included bark and left the hole in the center of the table. The base is simple, so the focus is on the slab of wood. Shibui in Japanese means unadorned elegance. While some people see the void, I see what is around it. This is a common element in a lot of my work: finding the simple beauty in the wood itself. People are drawn to it, but don’t necessarily understand exactly why.

“Leftovers can also inspire pieces. The Remnant cabinet is resawn and book-matched curly maple with a spalted maple panel. The basic design is a Shaker chimney cupboard, but it is made totally of leftover materials, remnants from another job. It’s a good example of how I approach design; I don’t generally draw things out, but simply start to build and design as I am building. I feel you should not rely on a set of plans to guide either what you make or how you live.

“The Shibui Butterfly Headboard, on the other hand, was an afterthought. Essentially, it is a book-matched, cracked slab of walnut tied with butterfly inlays, but there are a lot of other elements going on in that piece. There’s shape, figure and color all contributing to the texture of the piece. The pieces for it sat in my shop for years because I did not know what I wanted to do with them until this job presented itself. I was approached by a designer to do some furniture. After giving out a quote for the other work, I suggested that this headboard would blend nicely with the rest of the house. The owners fell in love with it after coming down to the shop to see the slab from which it was created.

“I often make personal connections with my clients, in spite of the fact that they often live a completely different lifestyle from mine. Many have become friends, but perhaps more importantly, they become part of the design and building process. That is as rewarding to them as it is to me.”

As for a life divided between wood, family and running a nonprofit to help others, John admits that there are challenges. “It’s not easy,” he confesses, “but it is worthwhile. Every time I just want to throw it all away and get a real job, something happens that keeps the fire alive in me.”