I’m not sure what the definition of a full-time woodworker is, but by any estimation, John Hampton, of Raymond, Washington, is full-time. To start with, he puts in more than 60 hours per week at Weyerhauser, the logging and wood manufacturing giant. That alone would keep most of us busy, but when John gets home, he spends his free time running a 30-acre tree farm and doing a wide range of woodworking, from turning hats and segmented bowls, to building furniture and toys, both as a hobby and a business. When I asked him how he manages to fit all that into a normal week, he replied “I don’t sleep a lot.”

It’s not as if he has a simpler life than most. He’s married with three children, one of whom still lives at home. There are also three grandchildren who frequently get the fruits of John’s woodworking prowess. By day, he works as head setup and grinder man caring for the planer at the Weyerhauser plant on Washington’s Olympic peninsula, an area southwest of Seattle.

The tool he maintains is no ordinary planer. It cuts dimensioned lumber, from 2 x 4’s through 2 x 10’s, ranging from eight to 20 feet in length. This six-head monster can cut a staggering 1,800 feet per minute, some one hundred times faster than the 12 to 18 feet per minute typical for the planers most of us use. Its bed is 12 feet long and three feet wide. Four heads define the four sides of the board, while the fifth and sixth cut and shape wide boards into two narrower ones.

Not long ago, a question sent into the eZine asked why mills round the edges of lumber. Having access to the guy who runs this rig presented me with a very timely opportunity to get that information straight from the horse’s mouth. “We round the edges to protect them from being damaged or dinged, to avoid slivers, and to give it a better appearance,” John explained, adding, “Weyerhauser uses a 3/16″ radius on their edge.”

Known in the area as a rather avuncular company, Weyerhauser does a lot for the community, and takes very good care of their employees. John is a second-generation employee, a situation not all that unusual. “My father worked for 47 years in the same Weyerhauser mill where I now work,” John told me. “I started working there after high school while I was in college, then switched to full-time shortly after graduation. I’ve been there 35 years.”

Coming from such a wood-centered region, it was no surprise that he took up woodworking early. “I started woodworking when I was 12, cutting and building beehive boxes for my grandfather. During high school, I took woodshop, but also helped with projects around the school: hanging doors, building trophy showcases and even rebuilding a baby grand piano for the auditorium.”

Once he had his own family, the hobby kicked into high gear. “I started building kids’ toys when they were little, then did furniture pieces for the house as I needed them. My kids went to a co-op preschool, where the parents contributed time and effort instead of just money. Parents spent time teaching and helping in a variety of ways; I built a lot of the furniture and toys.” In fact, he was once named “Mother of the Year” at the co-op preschool, having been there every day while his children were attending.

As others saw what he built for his family, they asked for copies, and the business side of his hobby was born. One summer, he recalls, he built and sold about 100 children’s picnic tables modeled after one he built for his own children. Anyone this busy must build quickly, and one telltale sign of how he does that is on the child’s booster seat he made. The plugs on the inside of the arms show the unmistakable mark of pocket joinery made with a Kreg jig. “Kreg is the best system I have found,” John told me, “and I’ve been using it for about five years now. It’s fast, easy and strong.”

Children also inspire toys, but not all toys go to children. One of his more impressive “toys” is a fully functional log loader, built for a man about to retire from his job running a log loader for Weyerhauser. It took John four months to build and is fully articulated, right down to the moving tractors. The jaws open and close, all the cylinders work, and it swivels 360 degrees, but it contains no metal parts, not even fasteners. He built two, kept one, and sold the other for the $100 he had quoted before starting the job. “I’ve been offered $500 for the other one, but turned it down.”

About five years ago, he discovered the lathe, and started turning everything from functional cowboy hats to segmented bowls and barley twist candlesticks. But his turnings have an unusual twist: they are made only from downed wood. “I only use salvaged wood and absolutely refuse to cut down a tree just to make a bowl,” John insists. “I use mainly downed trees and recycled wood taken from remodeling jobs. Around here, there’s no point in cutting trees for hobby work. There’s enough wood already down, lying there, going to waste, that I never need to cut trees.”

Some of his most striking turned objects are his custom fit wooden hats, which he started making after seeing one by Johannes Michelson, the father of wood hat turning. John’s hats are turned green from one large block of alder, maple, birch, beech, apple, pear, cherry or elm. Turning green allows him to form the brim into a variety of shapes and curves. “I have a jig that works with rubber bands to let me shape the various brims. It takes about three or four days during drying to set its shape, but I generally leave them in the form about a week.” The hat itself is under 1/8 of an inch thick and takes about 20 hours to craft — half the time in turning and half in bending and finish work. “A custom fit hat goes for $500 and comes with a display stand,” John said, adding “they’re fun to do.”

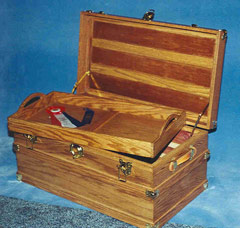

Beyond the fun, there are the honors. Two of his turnings and one of his hats took first place prizes at the Puyallup Fair, and a storage chest he made took the Grand Champion ribbon at the Pacific County Fair. Though some items get sold, he frequently donates pieces to “Hearts for Arts,” an art foundation that supports local artists. He also demonstrates and teaches at the county fair.

“I’m still learning,” he insists, “because everyone I teach, at any skill level, has something to teach me. Keep an open mind when you go to help others, because chances are, they are going to show you something you don’t know.”

What I don’t know is where he finds the time to do all this.