John Eugster recently retired from 30-plus years as a shop teacher – fitting, since his own first experiences with woodworking were in junior high shop class. To paraphrase some old commercials, he’s come a long way from junior high level projects; John’s woodworking in the past few years focuses mostly on pieces of his own design – and the more challenging, the better.

While those junior high shop classes may have jumpstarted his fascination with woodworking, it was a job as a teenager at a mom and pop hardware/lumber store that helped to cement it. “I would sometimes go out on deliveries with the raw material, and then I’d go back a week or two later and see tables and chairs,” John said. That planted the seed of the idea, in regard to building furniture, that “If somebody else can do it and charge me for it, I can do it cheaper.”

John’s plan after returning from military service in Vietnam in the early 1970s was to work in the construction industry, but a building lull made jobs scarce in that field. “I decided I liked wood, I liked kids, so I used the G.I. Bill to go to San Francisco State. That’s how I got into the teaching end of it,” John said.

Upon his graduation in 1977, the Las Vegas school district was the only one that offered him a job. John spent most of his teaching career focused on shop classes at the middle school level, although for the last 11 years, he taught at a boys’ prison that was included in the school district.

Sometimes, John said, he would run into former students, “Some would say they still do some woodworking. That’s always encouraging, running into old students who still do something with it” – despite, as he noted, the decline in woodshop offerings at schools. “To me, it’s kind of sad that people have lost that direct brain-to-hand connection,” he said. “I would always tell the kids, there’s something magical about it: you think of it, and you draw it, and you create it.”

That describes John’s own process of creating a piece, too. “I start my thought process with ‘How can I get from nothing to what’s in my mind?’ I draft things out on graph paper and work out plans.” For at least the past 10 to 15 years, John said, he’s been designing his own plans for the projects he builds.

“A lot of times, I will take on a project more for the challenge than for the financial gain. For me, it’s about the actual work: solving the problem,” John said. “It excites me to come up a with a piece somebody has envisioned.”

That was the case, for example, when he received a commission for a “mechanical cellarette.” (Click for a video.) When the client first contacted him, John had no idea what that was. It turned out to be a furniture piece similar to a buffet cabinet, with a bar that pops up out of it.

John said he really enjoyed building that piece (he accomplished the movement with a mechanism similar to a TV lift), as well as an armoire he built for himself, which was inspired by Thomas Moser’s “Dr. White’s Chest.” In contrast to that piece’s monolithic appearance, which wasn’t what he was looking for, John created a stepped effect with the drawer placement.

“A lot of times, somebody will say, ‘Oh, that’s a nice piece, you should make 100.’ That would be boring to me,” John said. “I like to get a challenge, and work through the challenge, and then move on to the next thing.”

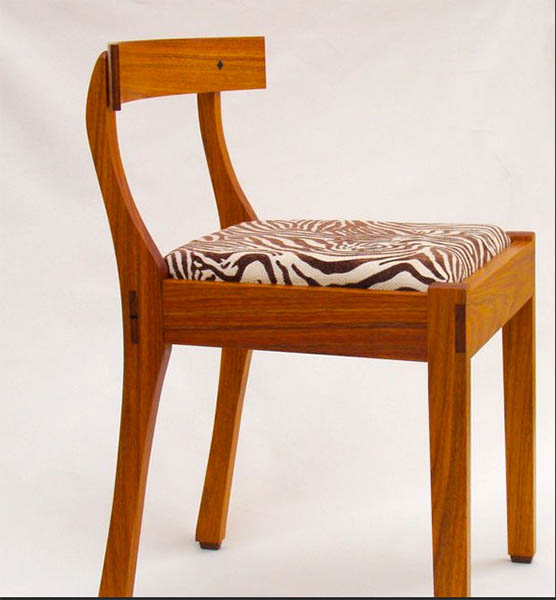

He has also added additional challenges to himself over the years, in moving more and more toward hand work on his projects. For instance, while he will use power tools to cut wood to thickness or to make initial cuts in larger pieces, after that, he will go to hand-cut dovetails, pegs, or mortise and tenons for joinery.

“I think of it as power tools being my apprentices and performing the grunt labor,” John said. “At this point, I’m doing primarily hand joinery and surfacing on my work. I prefer using a hand plane to create a smooth surface rather than sanding. I also prefer using a scratch stock to create details, rather than a router. The quietness of using hand tools and its result just doesn’t compare to the dust and noise of powered machinery.”

He also prefers a hand-rubbed oil finish, using a three-part top coat that is sanded in with very fine wet/dry abrasives. Although his students called it “the John finish,” he actually learned it at San Francisco State from Art Espenet Carpenter. “Very rarely will I stain a wood,” John said. “I prefer selecting a wood that has the coloration I’m after rather than dying or staining to get that color.”

Personally, he said, he loves working with exotic woods, such as bubinga and wenge. Making boxes out of smaller pieces of wood gives him a chance to experiment with these types of wood.

Of course, despite his love for challenging, one-off pieces, “I’ve got to pay the bills,” John said. His wife is an artist, and this has led him to pursue a niche of carving and gilding picture frames specifically tailored to artist’s pieces (he’s got a commission waiting for him that is meant to frame a seascape; the carvings will be “an ocean wave type thing”) as well as artist’s furniture. That includes things like easels, tailored to the particular angles and heights an artist might need, as well as wet panel carriers, which are a solution to the problem of carrying wet paintings out of, for example, a class at an artist’s school.

John makes such things for his wife, who carries them to workshops. “People see the stuff she has, and say, ‘Where’d you get that?’ ‘My husband made it.’ That leads to three or four orders. If I can make a couple hundred bucks, then I can buy exotic woods and do the more challenging items.”

Right now, however, all of John’s woodworking projects are on hold until he completes the renovations (ideally, by the end of this month) to his shop at a new retirement house in Phoenix. The property had an existing shop building, but it needed things like a bigger door and insulation, as well as air conditioning. “With the shop in Las Vegas, I would quit when it hit 105 degrees,” John said. “We decided we’re going to budget for air conditioning. That’s an exciting thing for me.”