It’s a long way from Ireland to Wyoming, with stop-offs in London; Watertown, South Dakota; and Minnesota’s Twin Cities along the way. That’s the road that John English followed to become a contributing editor for Woodworker’s Journal and frequent contributor to this eZine. Along the way, he’s carved out a unique niche for his wonderful shop-built jigs and deep interest in Arts and Crafts- style furniture.

It all started in Ireland. While growing up, John watched his father doing some serious amateur woodworking.

“My dad was just magic with his hands.” John recalled. “He grew up on a farm and just couldn’t leave things alone. I stood there and handed him things, but he never let me do anything. He was a perfectionist, and he couldn’t stand to watch people screw things up.”

In 1976, when John graduated from high school, there weren’t many prospects in Ireland. Unemployment was at 27 percent, and he decided to seek his fortune in London. There he found work as the night manager of a hotel and met an American from South Dakota who would become his wife. During his two years in London, he also happened upon pieces of English Arts and Crafts furniture in a museum. Though knowing little about it, he instinctively appreciated the style that would one day play a big role in his career.

The couple eventually decided to move over to the States and settled in Watertown, South Dakota. After working at a fast food place for six weeks, John found an apprenticeship at a cabinet shop. When the shop went bust, the Englishes settled in St. Paul, Minnesota, where John opened his own shop. Specializing in cabinet and woodwork repair, he eventually built a clientele among the stately homes along St. Paul’s Summit Avenue and in Minneapolis’s Kenwood neighborhood.

“Some of the best woodworking I’ve seen was on Summit Avenue,” John explained. “It was incredible working with carvings, leaded glass, turnings, that kind of stuff. The joinery was something else. It was all handmade or milled by very slow, precise machinery that hand-operated. Because they worked so slowly, they had time to look at the lumber, look at the grain and color patterns and match things a lot better than we do now. While doing the repair work, I learned how things are put together and began to understand there was more to life than plywood. The more you see of fine work, the more you want to do it.”

He also started writing while in the Twin Cities. He supplied home repair and how-to articles for weekly neighborhood newspapers. He also became U.S. correspondent for an Irish farm newspaper for three years. But then his woodworking career took a couple of new turns.

“One of my Kenwood customers was an Englishman named John Shorrock,” John noted, “who invited me to help set up a business manufacturing English-style, laminated coasters and placemats for corporate clients. I built the factory, created machines, and developed the processes required to start the business. But once everything was in place and doing the same thing over and over, I got bored, so I also started selling architectural millwork for Shaw Lumber in St. Paul.”

Around that time, in 1991, he and his family moved over to Somerset, Wisconsin, just across the border from Minnesota. Still working for Shaw Lumber, he started writing a weekly column on DIY and woodworking for the New Richmond News. Then one day, one of the project managers came in and showed John a want ad. It was for an editor at Today’s Woodworker, a magazine then published by Rockler Companies. The part-time position soon became full-time, and John was associate editor when the publication was merged with Woodworker’s Journal in 1998. And even with his move to Casper, Wyoming, a couple of years ago, he’s worked as a contributing editor for WJ ever since.

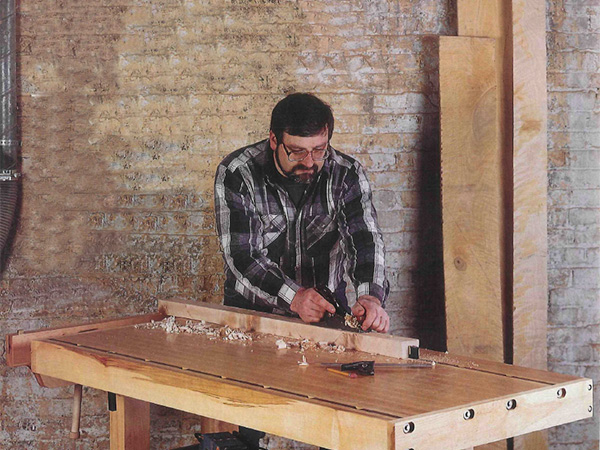

Today, you’ll find his furniture and jigs the centerpiece of regular articles in the Journal. Who comes up with the ideas?

“For a while, the projects were half mine and half the magazine’s,” John explained. “Nowadays they’re all mine, they don’t give me assignments. I spend most of my time building jigs for the shop, they end up on my shop wall, and a lot of them end up in the magazine. The more ingenious the jig the better.”

Since he started working on the magazine, John has also deepened his long-time interest in the Arts and Crafts movement and its origin in England.

“There’s a lot of attention to the work of the Stickley brothers, Greene and Greene, and Frank Lloyd Wright, but nothing on the British Arts and Crafts which preceded and inspired the Americans. There are similarities: both used a lot of quartersawn oak, which, aside from its beauty, has a tighter grain that doesn’t move or warp as much as a plain-sawn board. To be quite frank, the Americans were better at it, probably because somebody else had started it, and they took it over. But there are some very interesting characters on the British side, and I want to go back to its roots.”

To that end, John is planning a trip to England next year to revisit some of those museums from his days living in London and other Arts and Crafts sites where he plans to document and photograph prime examples for an upcoming book.

“Even interest in England is just starting.” John explained, “but original dressers or tables that went for $300 or $400 five years ago are now going for $1,500, and it’s starting to pick up fast.”

And for his new web site on the subject (currently under construction), he’s building a writing desk library bureau originally created by Harris Lebus, a British Arts and Crafts manufacturer. It’ll undoubtedly be as good as, if not better than, the original. You see, like his father, John is a perfectionist. And these days, it’s his kids who hand him tools in the shop.