You never know about second careers. Sometimes they fizzle and sometimes they sizzle. Joe Petrovich’s is sizzling. For the past twenty-plus years, he’s built up a thriving woodworking business in Salinas, California (about 100 miles south of San Francisco). He builds a variety of pieces for his mostly affluent clients in styles ranging from eclectic to Craftsman to Danish Modern. Plus he writes about woodworking – his article about constructing a bombe jewelry box is featured in the Woodworker’s Journal.

Sound like a full, successful career all by itself. But before Joe became a full-time woodworker, he spent 27 years as an Army infantry officer – serving two tours in Vietnam and one in Korea, as well as numerous billets around the states. During 17 moves, Joe carried along a footlocker full of hand tools. Unfortunately, serving as a company commander or platoon leader left him little time for woodworking – until his last assignment brought him to Fort Ord, California.

“During my last three or four years in the service,” Joe recalled, “I was stationed right across the street from the base’s Special Services woodshop, and that’s how I ended up here. After spending most of my life on the East Coast with its really rotten weather, there was something really appealing about a place where people complained about having to put on a windbreaker.”

So after retirement from the Army, he and his family decided to settle in nearby Salinas. Up to that point, he’d done little woodworking, mostly just small items as gifts. Most of what he knew about woodworking came from old Popular Mechanics and Popular Science articles back in the 1950s and then from Fine Woodworking when it came out in the 1970s. (Joe later wrote for FW.) But despite having no formal training, Joe decided to become a professional woodworker. That was 1980. It was slow at first; there weren’t that many commissions. Along the way, Joe and a friend got involved with salvaging old grapevine stakes, which are made of Malaysian hardwood. That in turn got him involved in importing wood from Malaysia for a few years. But as his reputation grew — mostly by word of mouth — so did his woodworking business.

“I think you have to be in the business for about eight to 10 years to get established,” Joe explained. “I used to do lots of kitchen cabinets, but it’s a lot of work and hard for a small cabinet shop to compete with big shops. Now I do my best to spend most of my time on things like chairs, desks, and tables.”

Today, Joe’s pretty much booked solid for the next six to nine months out, and when people call about commissions, it’s usually going to be a while before he can even talk to them about it. One of the factors that makes Joe’s work so popular is his versatility.

“I have some eclectic clients in Carmel, and it’s fun doing that sort of thing. And I have some clients in Monterey who are really arts and crafts kind of folks. And I have a big client who loves Danish Modern, so I get to do a lot of everything.”

Joe hasn’t experienced the business slump that has affected so many professionals. With even fixer-upper houses going for up to a million dollars in nearby Carmel, Pacific Grove, and Pebble Beach, there are lots of folks nearby who can afford hand-made furniture and, according to Joe, they’re always looking for somebody to do something.

“I built conference tables for a couple of organizations and when I asked about a budget, they looked at me like they’d never heard of one,” Joe explained. “But I also have a couple of clients who are no wealthier than I am – they are just willing to save up and pay for it.”

Joe approaches each project by looking at what the client already has and then doing lots of drawings – depending on the size of the project – up to a half dozen drawings until he’s satisfied. Then he presents a couple to the client, and he may build a small-scale model. But no matter what the style, Joe takes a traditional and practical approach to his woodworking.

“I haven’t found anything better than mortise and tenon, or dovetail or box joint. Probably all of us go through a period where we’re purists and will use only hand tools ? but then realize that what we’re after is the end result. Each piece is going to be around a lot longer than I am, and I want to put the best work out there. If that means using power equipment, I’ll use power equipment. If it means doing it by hand then, by golly, I’ll do that. It’s just a matter of common sense.”

The location of Joe’s well-equipped shop is the same place he started with in 1980 – the garage next to his house. Though he’s had apprentices over the years, he currently works alone, usually working in the shop first thing in the morning and then doing paperwork in the afternoon, because, as he puts it, “my brain is clear in afternoon, but my body is sounder in the morning”. When he needs to get away from woodworking, he turns to another craft: toolmaking.

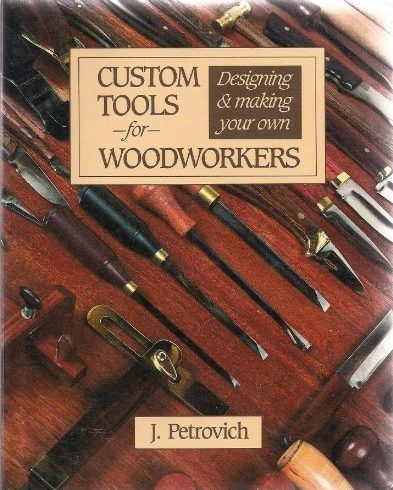

“I was always fooling around making tools because my dad was a tool-and-die maker. A friend of mine, Alex Weyger, noticed that I was always making gouges and stuff and said all I needed was a forge. So I got started, ended up with two forges, and have been doing it ever since. It’s a handy skill for a woodworker. Once in a while, I need an unusual piece of hardware that I only need once. Old saws have great steel for bench knives. I even wrote a book about it [Custom Tools for Woodworkers: Designing and Making Your Own] in 1990.”

Which brings us back to his third second career – as a writer. When not in the field during his Army career, Joe’s staff assignments usually involved writing. Though he describes a lot of it as writing dreary infantry regulations, it was good exercise. In fact, he’s going to be documenting his next woodworking project – a Craftsman-style clock – for another article in Woodworker’s Journal.