Jason Bedre says he’s been interested in woodworking “forever,” ever since he used to accompany his grandfather on the weekends, either to a workshop or when the grandfather built nets and frames for shrimp boats. “I used to love to go up there with him on the weekend,” Jason said.

Most recently, however, he began building things for his house after getting married about 12 years ago; friends saw them and asked him to build things for them; then it became friends of friends — and it went from there. “I rarely build things for myself anymore,” Jason said, even though woodworking is still not his “day job.”

Instead, Jason works as a polymer chemist, which he says gives him a unique insight into the finishing aspect of woodworking. “I don’t make finishes, but the chemistry is the same,” he said. “I kind of delve into the science behind it.” He says he’s finding that newer waterborne finishes are an alternative to lacquer that they weren’t even seven or eight years ago. “Now my number one finish is General Finishes Enduro-Var. Its ease of use rivals any lacquer, at least in my hands it does,” he said. “I’m not trying to use green finishes, I just think they’re becoming more durable.”

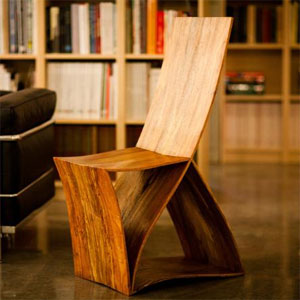

As for his actual woodworking pieces, Jason says he’s best known for his unusual chairs. “I particularly enjoy building chairs. In my opinion, all aspects of woodworking go into it: proportion, design, functionality. It has to look good, but you have to be able to sit in it.”

One of his chairs, “Curvis Sedis II,” is particularly memorable. It’s got complex joinery of interlocking dovetails, as well as spline dovetails, a covered seat that’s tapered to the edge, and a frame made of bent laminations. “It was a real test of seeing how far I could go, and push the limits of what I could do, to make it. I was sort of challenging myself, I guess,” Jason said.

Another chair in Jason’s work has a coopered seat, instead of steambent. “I wanted the grain to run perpendicular to the curve,” he said. “Right now, I’m really into the coopering technique, because not many people do it.”

As for other techniques, Jason said, “I like bent laminations; I like hand-cut dovetails — I like the way they look.” Also, he said, “It’s taken me about 12 years to appreciate hand tools in a major way. I’ll use a power tool if it will do the job better, but I can at least now appreciate when a hand tool is the appropriate choice.”

For wood choices, “I like to use local woods, but it’s not my main thing,” Jason said. He just finished a desk made from a spalted pecan that fell near him, but the desk also has a walnut top and turned wenge feet, while his dad’s position as a groundskeeper at a golf course on the Texas Gulf Coast has meant Jason had access to some mesquite that had to be cut down. He’s also currently working on a piece with boards he sawed and air dried for three and a half years which came from an elm tree in his front yard that died. But, he said, “We don’t have a substitute for mahogany that grows in Texas.”

Most of Jason’s pieces have a contemporary style, largely because “I do not like to copy anything,” he said. When potential customers approach him about building something they’ve seen in a furniture store, “If they’re happy with those there, I tell ’em to go buy it. It will be two to three times more if I build it. Some people don’t understand how much work goes into making a handmade piece.”