Several years ago, J. Paul Fennell was working as an engineer in the aerospace industry, a stressful, highly analytical job. So, for a leisure activity, he sought out something hands-on.

Since he was living at the time very near a high school with a sparkling new woodshop – and had had fun as a boy playing with scraps of wood and nailing things together in his father’s basement shop – that choice for Paul was taking a community education woodworking class – where he noticed several unused lathes sitting in the shop.

Once the teacher gave him permission to use the lathes, it set things in motion for Paul. At first, he liked turning because it was fast: “It was more enjoyable than spending a long time building one piece of furniture. On a lathe, you can make several things quickly.”

Then, he began developing his skills, reading about turning, participating in online chats and forums and making turned pieces which tended more toward the artistic rather than the functional side of things. Interested buyers and galleries began contacting him. Although he kept his day job for a long time – “it’s very difficult to make a living as an artist and raise a family at the same time” – turning, for Paul, “became something of an avocation.”

His signature pieces combine his interests in both technical and aesthetic challenges, Paul said. During their creation, “you relate all your life experiences; they’re all mixed up in the creative process.”

For instance, one of his series, the De la Mer series, explores his memories of growing up near the ocean in Maine. “It’s something I didn’t think about” earlier, he said. “I happened to live near the ocean; some people didn’t. I found it was a memory I wanted to explore in a creative manner.” So, he created a series based around design elements that conveyed ideas of ocean waves.

Others of his series focus on natural patterns. “I was able to identify a great number of patterns found in nature,” Paul said. “It develops out of ‘seeing,’ such as a photographer does.”

Paul doesn’t like to stick with the same sort of thing for too long, though. “I’m curious about doing things differently and taking chances,” he said. “I don’t feel too comfortable staying within boundaries; there’s no challenge there.”

For instance, in the early 1990s, he was focusing on creating very thin-walled pieces using a fiber optics system. The turned pieces were thin enough that, when turning, the walls became translucent.

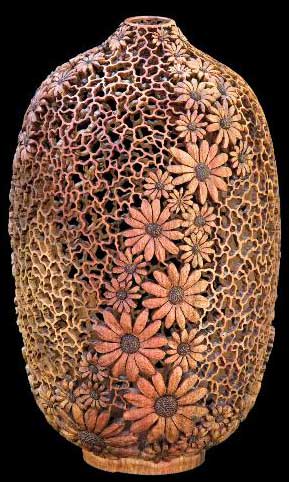

Now, although he may still use fiber optics to gauge wall thickness, “I’ve gone on beyond that” to focus on several more alternative techniques. “I’m doing a lot of carving and pierced work right now,” he said. For one instance, he cited pieces which resemble a thin ribbon going from the top of a piece to the bottom. “It’s very challenging. I’m doing similar pieces like that right now,” Paul said.

He’ll sometimes even invent his own tool to accomplish a technique he’s envisioned. “I have to develop a special tool to do something if I’ve created a situation where nothing would work,” he said. “I like the particular challenge of doing things no standard tools allow you to do. If I develop one, it may be used once or twice – but the idea of innovation appeals to me.”

One of those tools allowed him to create pierced backgrounds on his turned pieces, because “there wasn’t any standard tool to do that sort of thing.” Lately, he’s been interested in indexing on the lathe, except, instead of being limited to the standard division of a surface with evenly spaced straight lines, he wanted to create curves.

“With the curves, if you’re able to carve them or do certain things to one surface, then you can do it to any piece,” Paul said – and he’s now applying the technique to a piece, Ad Astra, made from some salvaged tulipwood poplar from Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello estate. Paul got the piece of wood from the Historical Woods of America organization, which required him to use it to make something that had relevance to the place of the wood’s historic origin. Paul’s choice was to use his techniques to imply Jefferson’s interest in science.

Using salvaged woods isn’t unusual for him, though: “All the wood I use is salvaged,” he said, meaning it doesn’t come from commercial enterprises but is instead salvaged from trees cut or blown down in people’s yards or city streets. Since he now lives in Phoenix, Arizona, where many exotic woods have been imported and grown in the climate, this means he uses woods like mesquite, African sumac and carob. “In woodturning, a lot of people have the same sense of environmental responsibility.”

Paul, who is now doing a lot of demonstrating and teaching of woodturning, also added that, “We tell people that it’s OK to copy other people’s work in order to learn technique, but once you learn the technique, you should go beyond that, and start thinking about doing work that is unique. Most of my work is on that basis – it’s based on how I think about things and so forth.”