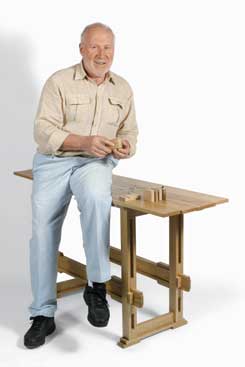

In a 40+ year career that’s included woodworking, writing, designing, teaching and consulting, Ian Kirby has achieved national renown. First in his native England, then in the United States since 1973, Ian’s practical approach to teaching and practicing his craft has influenced generations of woodworkers.

In many ways, Ian Kirby’s furniture building and design skills trace their lineage to the Arts and Crafts movement in England. Though it was eclipsed some 50 years before Ian began his training, his early understanding of the movement’s philosophy had as much influence as his subsequent training in design, joinery, and wood science.

It all started in 1952, when Ian began his study of woodworking. The Arts and Crafts movement had already heavily influenced the teachers at his school, but Ian’s training also coincided with the time frame of visiting tutor Edward Barnsley’s tenure.

“Barnsley was a product of his father, Sidney, and uncle, Ernest, who had been heavily involved in the Arts and Crafts movement right from the beginning.” Ian explained, “Today the movement is very poorly understood. Based on the writings of William Morris, it combined the use of the best material — native English wood, quartersawn and carefully selected — with hand production. It means you create a universal methodology and a universal working method and a universal set of terms. Since the working methods were based around hand tools, the design is going to be dead simple, so the furniture has a similar look and feel. While in the United States, manufacturers like Stickley had no interest in using handwork tools and figured out how to make furniture that looked liked it was ‘Arts and Crafts’ as easily and cheaply as possible.”

The solid wood furniture Ian made during this time was a very refined form of Arts and Crafts, and he felt extremely well-grounded and very knowledgeable Yet, after three years of very intense study, he knew there was something missing in his training.

“More than once I have heard Edward Barnsley say that he wished he knew more about design. But it wasn’t until I got to art school that I knew that was the key that both he and I were missing.”

Ian began to remedy that shortcoming in 1956. While he pursued the study of wood science and wood technology at Howe College of Technology, he also taught a furniture-making class. And in his free time, he started attending life-drawing classes. When his wood science degree was complete, he enrolled in a four-year design program at the Leeds College of Art. He feels lucky to have had some of the best teachers and training in design, drawing, and color and was awarded a National Diploma in Design in 1962. Advanced courses in furniture materials, furniture finishes, and furniture design at the London School of Furniture rounded out his education.

“I was able to study with one superb teacher after another, first in the workshops, and then in studios and laboratories.” Ian noted, “My period of study started in about 1952 and ended in 1964 & a ludicrous length of time. I could have become a neurologist in the time I spent, but I just thoroughly enjoyed it!”

With degrees in design, wood science and technology, and furniture making, Ian began a 14-year career of teaching at London University and operating his own interior design studio, with his wife Rosalind.

“We took on interiors where we did the whole thing…the walls, the furniture, the carpets, the fabrics & I am as happy talking about cloth as I am talking about wood.”

On a 1973 sabbatical, he came to the U.S. to teach at California State Los Angeles and returned again in 1975 to teach at the School for American Craftsmen at Rochester Institute of Technology in New York.

“I saw what was happening on the West Coast. There was furniture being made that was very creative, but it was sorely lacking in an understanding of techniques. I also realized that I wanted to move to the U.S., and my opportunity came when I was invited to join a community of artisans in North Adams, Massachusetts to start a school of furniture-making, which we opened in October 1976.”

Ian had 20 students within six months and moved his school to a larger studio in Bennington, Vermont. The school was becoming a center for furniture education and drew up to 36 students from throughout the country.

“My wife is a ceramicist and a silkscreen printer and taught with me.” Ian recalled, “We had a huge library and had this terrific group of people who ran the shop. The object of the type of teaching I did was to get the best out of what each person could do. To train a designer, you lay the groundwork, but you have to get them to develop to be themselves. To be a great woodworker, you first have to be great designer. And what you can’t do is turn out little clones of yourself. It is very important as a design teacher that you don’t let the student become a mirror image of yourself.”

Around the same period, Ian began writing articles for national magazines (“Fine Woodworking” and “Woodworker’s Journal” were just coming out) and started a residential furniture manufacturing company, Kirby Apter Design. By 1983, the studio had grown “so big” that Ian felt the school needed a change of setting.

“Our students were from all over America, mostly from urban areas, and we needed to be in a more urban environment where there were museums. New York scared us, so we chose Atlanta as the new site. We did quite well there.”

The school opened at the right time to ride a wave of interest in woodworking. In 1987, when the economy took a downturn and the wave of interest ebbed, the school closed. Ian then worked as a consultant for Weyerhaeuser.

“I was working with one of their marketing groups developing the sale of clear timber called ‘Choice Wood.’ We put a lot of time and effort in and we were making them a lot of money. But Weyerhaeuser didn’t really like being in retail, and they closed the division.”

In the meantime, Ian produced a series of woodworking books, began designing homes for clients across the country, and started teaching in San Diego.

“There were great people in those classes.” Ian recalled, “Four of my students entered the IWF Furniture Student Design competition, and one of them won in his category and Best in Show!”

Finished with teaching for a while in 1994, Ian spent a year designing homes in Bel Air & mostly for people involved in the movie industry. Quite a number of his designs have been featured in Architectural Digest.

Today he continues to design, teach, and build furniture.

“I have an interest in getting a learning program online.” Ian explained, “One of the things I finally have realized is that there’s a dichotomy between the way English people are taught woodwork and the way Americans are taught. The English say ‘here is the tool; here is how it works, and now learn how to use it.’ They learn to make a joint by practice and then throw it away. American won’t do that; they have to make something that they can walk out with at the end. There is something right about both methods. I’m developing a course where I can mix the two things together.

“I’m developing a line of furniture that I want to make. It will still retain all of the Arts and Crafts techniques of holding solid wood together, but using modern machines. There are still books and woodworking articles to write. One of the books that I would like to write is on understanding Arts and Crafts furniture.”

Ian believes that furniture should be designed to solve a problem. “I don’t feel a need to produce artistic furniture…functional furniture is artistic by its nature. If you are going to train a furniture designer, the last thing that you want them to learn is how to make a mortise and tenon or dovetail joints. Furniture design is about making, call it what you will, interior design architecture & but is not about woodworking. The two things are quite different. If you train somebody to be a woodworker and you give them a design problem they will always turn to wood and to those methods that they know and understand. You could make a chair out of all the most comfortable materials and make it as uncomfortable as all-get-out if you didn’t get the angles and heights correct. This is what designing is about.”