The Greenville Woodworkers Guild is bigger than many, both in membership and in physical space. Roughly 950 people are part of the South Carolina organization, which owns a building with over 20,000 square ft of space that houses both a shop and a lecture hall that regularly hosts woodworkers from across the country.

What’s the secret to the Guild’s success? Current president Charlie LeGrand says, “The mission is what has set us apart.” The Guild’s three-part mission statement focuses on educating members, educating the public about woodworking as an art and charitable works. For LeGrand, “Educating our members and charity work are the two most important aspects of the Guild,” with the two mission goals often completed in tandem.

“We’re not a shop for hire, and we try to emphasize that to people as they consider joining,” LeGrand says. “We are a community of like-minded individuals who share an interest in a hobby.”

The now-required pre-membership meetings for those who are thinking about joining emphasize the equality and responsibility among Guild members. There are no paid employees, and “if you break something, you need to fix it. If there’s dirt on the floor, you need to sweep it up. Don’t just come in here and use the shop and leave; we expect you to participate,” LeGrand says.

The ethos of everyone pitching in was evident in the acquisition of the current shop building, which the Guild has been operating out of since 2011. The former retail site was acquired with a monetary donation from member Bobby Hartness; for construction renovations, members not only contributed financially but also put in 6,500 labor-hours in 907 work sessions with 252 volunteers, according to Going with the Grain, a book charting the Guild’s history, written by member Aubrey Rogers.

Big Shop, Big Names

Now, the building includes a machine room with power tools that include a 5hp SawStop table saw, 10″ and 12″ Grizzly table saws, 16″ Oliver jointer/planer and 25″ planer, Festool Kapex miter saw, Laguna 16″ band saw, two CNC machines, a laser engraver and more. In addition to two lathes in the main shop, there’s a dedicated lathe training room with six more JET lathes, plus even more lathes in a youth program room.

“We have an assembly area; we have an enclosed sanding booth; we have a pretty good-sized hand tool room which right now doubles as a finishing room. So it’s a big place,” LeGrand says. Additionally, the building houses a woodworking library, conference room, lumber room and auditorium. An outbuilding stores extra wood.

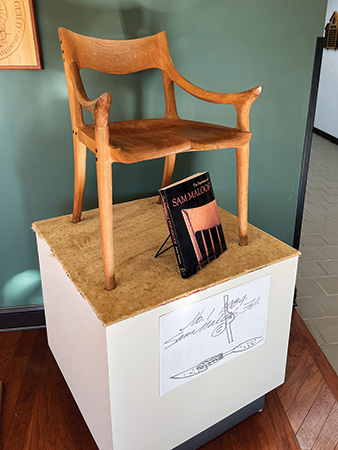

The 300-seat auditorium is the current site for visiting lecturers, but that program predates today’s shop. Sam Maloof built a chair in a member’s garage shop in the 1980s; Ian Kirby spoke on design; Frank Klausz did a session on dovetails. More recent speakers have included Roy Underhill, woodcarver Mary May, Alf Sharp on marquetry, David Finck, and Tom McLaughlin of Epic Woodworking, whose all-day presentation last year “covered everything” about the tables he was building, LeGrand says. “He did it right here on the stage, veneering a curved piece to shaping a table leg while we watched.”

Presenters will also do hands-on seminars of varying lengths. Finck, currently a luthier who studied with James Krenov, “had us making Krenov-style hand planes,” LeGrand says, while a four-day session “had 10 students learning to carve from Mary May in our bench room.”

Charitable Projects

The educational aspect of the Guild also ties into its charity work. For instance, a Guild team of toymakers meets weekly from April through November to create playthings for children’s charities — 1,532 were delivered in 2023. “You might be on the John Deere tractor team, or somebody else might be on the airplane team,” LeGrand says. “If anybody comes in and they’re new or they’re nervous about, let’s say, using a router table, by the time you make 65 John Deere tractors and round over the edges, you’re probably pretty good at it at that point.”

Guild member and retired professional woodworker Jon Rauschenbach is currently leading charitable cabinetmaking projects for the Guild. “He’s educating our members at the same time that they’re completing these charity projects,” LeGrand says.

Additional charitable builds of the Greenville Woodworkers Guild include lidded bowls for medical care recipients to collect Beads of Courage, Urns for Veterans to encase cremains in veterans’ cemeteries and numerous projects for the Meyer Center, a Greenville organization focused on empowering children with disabilities, among many others.

The Guild has been building projects for the Meyer Center since shortly after its founding, which occurred on June 1, 1981. Art Welling, one of the five founding members, had seen another woodworker’s business card that proclaimed him a member of the New England Woodworkers Guild and thought such a membership sounded like it would enhance his credibility as he worked to establish a high-end furniture business. The Guild itself, however, has always existed “for charitable, educational and artistic purposes only.”

A current educational aspect is the youth program. Offered on weekdays during the school year, its enrollees are mostly homeschoolers. “We’re not a trade school and don’t intend to be,” LeGrand says. “You’re teaching woodworking, but really what you’re doing is using woodworking to develop their brains” through math calculations, project planning, wood knowledge, finishing and more. “It’s a good hobby and develops their brains, just like it keeps old folks’ brains active.”

Many of the retirees currently active in the Guild are former Michelin engineers. In addition to the tire company, BMW and General Electric are major employers in the area. LeGrand thinks many in the profession turn to woodworking as a hobby because “it can satisfy their need for precision in measurement.”

Lumber Program

Membership isn’t for everyone, though. In addition to the nonprofit Guild not allowing its shop to be used to make items for sale, they also don’t allow the use of reclaimed wood, pallet boards or Southern yellow pine on their machinery. “The resin gums up the blades and it clogs up the dust collection system,” LeGrand explains. “Anything that could damage the machinery” is not allowed, “but anything else you’re free to bring in — or use what we have,” he says.

The lumber available for members’ use and purchase includes species such as Eastern white pine, poplar, cherry, red and white oak, walnut, padauk, purpleheart, Spanish cedar, sapele and canarywood.

The Guild’s lumber program, like a mentorship program that pairs more experienced woodworkers with those with less experience, has been an ongoing part of Guild activities for several years. The mentorship program began decades ago in each other’s home shops, prior to the Guild having its own building that operates throughout the week. An earlier 1,000-square-ft shop operated from 2003 to 2011 out of an industrial building Hartness leased to the group.

While members do still work in their own shops, the Guild tracked about 40,000 hours of work in its current shop in 2021, which includes both time dedicated to Guild charity work and personal projects. “Other guilds — this is not a criticism of them — but other places, you pay for and reserve shop time,” LeGrand says. That’s not how the Greenville Woodworkers Guild, whose current annual dues are $150, operates.

Instead, “The mission is what has set us apart,” LeGrand says. “For 42 years, it’s set us apart.”

For more information, visit greenvillewoodworkers.com.