This queen-size bedframe began as a conversation with my wife’s former boss, Jo Ellen, about two years ago. She loves the “softer” cloud-lifted details of Greene & Greene style that give it a more relaxed look than Stickley’s straight lines and stout proportions. And she’s not alone. Lately, it seems, woodworkers are churning out Greene brothers furniture with particular gusto. So, it didn’t take much convincing when I offered to build this first piece in her new bedroom set.

Thanks to some excellent drafting by our senior art director, Jeff Jacobson, the bed was off to a great start. If you like what you see, gather up some 6/4 mahogany and maybe some fancier figured 4/4 stock for the bed’s center panels. Buy a sheet of quality plywood, too: you’re going to need it to make a stack of templates and jigs.

Starting with Four Big Templates and Two “Minis”

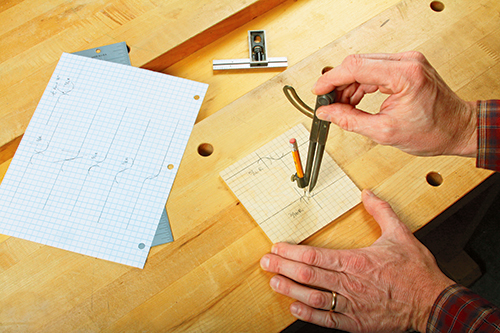

Look closely at the photo of the bed, and you’ll see that this bedframe has two sizes of “S”-shaped cloud lifts: tiny ones at the crests of the top rails, then a series of larger repeats that ripple down the top and bottom rails and the legs. These larger ones match one another. The smaller size is based on a pair of 3/16″-radii circles with centers that are spaced 3/8″ apart. Their opposing curves meet two horizontal lines that are 1/4″ apart (vertically), and the circles’ circumferences just touch. The larger cloud lifts start as 5/16″-radius circles with centers that are 3/4″ apart. Their edges intersect two parallel lines that are 1/2″ apart, vertically. A short diagonal connects the curves. Draw each of these cloud lifts onto squares of 1/4″-thick scrap. Cut them out and sand the shapes carefully on a spindle or drum sander. These “mini” templates will serve as tracing and routing guides for making the bed’s larger templates.

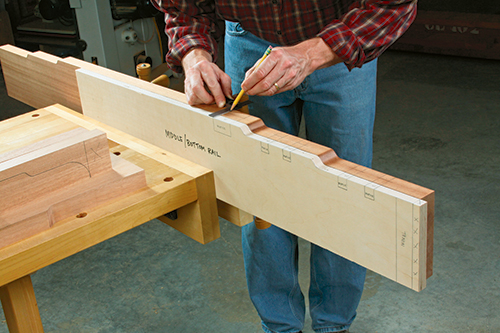

And that is your next task. I made four primary templates for the project: two half templates for the top and bottom rails, plus full templates for the two leg sizes. They’re necessary for tracing the actual project parts to shape, then template-routing them to final size. I also plotted the various mortise locations on my templates so they would perform double-duty as “story sticks” for the joinery. Draw your full-size templates, making the top and bottom rail templates at least half the total length of the rails. Then cut them out at the band saw and use your mini cloud lift templates, stuck in place with carpet tape, to template-rout the “S” shapes onto the larger templates. That way, all the cloud lifts will be precise and consistent from here forward. One other note: as you shape the bottom edge of the top rail template and the top edge of the bottom rail template, do your best to make their edges mirror opposites so the templates can literally fit together. What’s most important is that their flat surfaces are straight and parallel with one another.

Shaping and Mortising the Rails and Legs

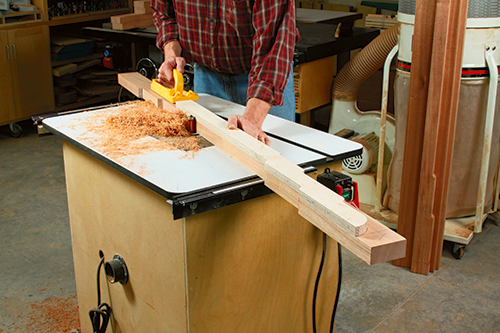

Head to the jointer and planer to surface enough 6/4 mahogany down to 1-3⁄8″ thick for the top rails and legs. From there, adjust the planer to 1-1⁄8″ and mill stock for the bottom rails and the headboard’s frame rail. When you crosscut the parts to rough length, allow an extra couple inches on each end of the top rails; you’ll cut that off after mortising them. Rip these blanks to final width, and use your templates to trace the parts to shape.

There’s an urge I sometimes get once parts are drawn, to cut them all out. If you share that impulse, stuff it down deep for this project. Making these rails and legs should happen in stages that involve cutting, template-routing and mortising — and not always in that order — with the goal of keeping flat reference edges as long as possible. They’re needed for stable mortising.

Start by band-sawing just the inside edge of the headboard and footboard top rails and the top edges of the bottom rails to about 1/16″ from your layout lines. Now stick your templates along the traced lines with double-sided tape, and use a piloted flush-trim bit to mill the excess off at the router table. Be careful of reversing grain direction here at the halfway point of these project parts; I flipped and retaped the templates to the opposite part faces in order to always keep the bit cutting “with” the grain: avoid tearout at all costs.

With these selected edges now shaped, lay out all the slat and stile mortises, centering them on the rail thicknesses. See the Drawings for mortise lengths.

I deliberated at length about my mortising tool options: Festool Domino, mortising machine, router with edge guide or drill press and Forstner bit. Because of the close proximity of the slat mortises to some of the cloud lifts, that eliminated the Domino. A handheld router on these part edges might have been teetery, and the wide bottom rails exceeded my mortiser’s “bite.” So, the drill press, outfitted with a 4-ft. straightedge fence and support table I made, was the best choice for machining these long, heavy workpieces. Bore the mortises 1″ deep for the stiles and 3/4″ deep for the slats, using a series of side-by-side plunges with your Forstner bits. Make the leg mortises at the ends of the top rails 7/8″ deep — the extra stock you’ve left here prevents the mortise end walls from breaking. If you repeat the drilling sequence several times over, you should be able to remove nearly all the waste so you’re left with assembly-ready mortises.

Now clamp the rails upright and chisel their mortise ends square. Once that work is done, the flat reference edges of the top rails are no longer needed. Rough-cut, then template-rout, these remaining edges into their cloud-lifted shapes.

Turning to the Legs and Tenons

You can employ the same drill press setup now to drill 5″-long mortises into the legs’ inner edges for the rails — two in each headboard leg and one in the footboard legs. Make these slots 1/2″ wide and 1-1⁄4″ deep, centered on the leg thicknesses. But, before you head to the band saw to cut cloud lifts into the outside edges of the legs, stop! Mill their top tenons first. These 5/8″-thick, 1″-wide tenons are offset on the ends of the legs (see the Drawings). The shoulders that face the cloud-lifted edges are 1/2″ wide, while the opposite shoulders are just 1/4″ wide. I cut them at the table saw with a dado blade, backing up the long leg workpieces with an auxiliary fence attached to my saw’s miter gauge. Because of the various shoulder sizes, definitely make these cuts on scrap first, so you can adjust your saw settings carefully. Once you’ve cut them, check for a friction fit of the leg tenons in their top-rail mortises. When you’re satisfied, band-saw and template-rout cloud lifts into the outer leg edges, then file or sand their bottom corners to 1/4″ radii.

Take some time now to touch up all the cloud lifts on the rails and legs before proceeding. I used a 1/2″-diameter, 120-grit sanding sleeve in my spindle sander to remove any burn marks and rough-grain areas that resulted during routing, then switched to finer-grit papers wrapped around a dowel to go over them all by hand. It’s tedious work, but necessary nevertheless.

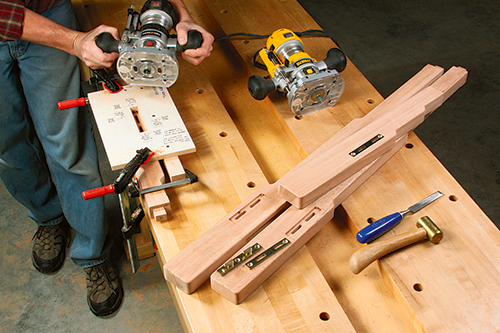

With the leg mortises made, there’s still the matter of cutting matching tenons into the ends of the bottom and frame rails to fit. Since these rails are now shaped, and no longer suitable for tenoning on the table saw, I milled the tenons with a handheld router and a slip-on, “wraparound” style jig. A 1″ O.D. guide bushing followed the edges of the jig, and a 3/4″-diameter straight bit made the cuts. I milled the tenons in stages, routing the 3/8″ shoulders into each face, then shifting the jig back to expose more area for routing. Cut the end shoulders with a hand saw.

Forming the Stiles and Slats

Dry-assemble the rails and legs so you can verify the exact length of the 16 slats and four stiles you need to make, next. Once you’ve milled stock for these parts — the slats and stiles are 7/8″ and 1-1⁄8″ thick, respectively — rip them to width and cut them to length. Switch to a stacked dado blade in your table saw and raise all their tenons. Once those are made, try them in their mortises, and pare them down, if needed, with a shoulder or rabbeting plane to achieve a nice, friction fit. Then dry-assemble the slats, stiles, rails and legs to check your progress.

Next, it’s time to mill the 5/8″-wide, 3/8″-deep grooves that will house the headboard and footboard center panels. You can cut these along the full inside edges of the stiles, and between the stile mortises on the bottom rails, with a slot cutter or straight bit at the router table. Feed the workpieces along the fence in the usual way, centering the grooves on the part thicknesses. But, these grooves also must be cut along the inside edges of the top rails between the stile mortises…and a standard router table setup won’t do. That’s because the innermost cloud lifts will interfere with a long fence.

So, I took a different tack. I made a “short” fence jig from doubled-up plywood. It gave me bearing surfaces on either side of my slot cutter that were short enough to allow the cutter to reach the mortise termination points. It also enabled me to adjust the bit’s projection out from the fence so I could cut these grooves in several deepening passes. The jig worked just as I hoped it would for this job.

Panel-making and Pre-finishing

Glue up a couple of attractive center panels for your headboard and footboard. You can make them 5/8″ thick for a flat-panel style, but I thought some dramatic shadow lines would look great here. So, I opted for 7/8″-thick panels and scooped out a 1-1⁄8″-wide, 1/4″-deep cove all around with a panel-raising bit in the router table.

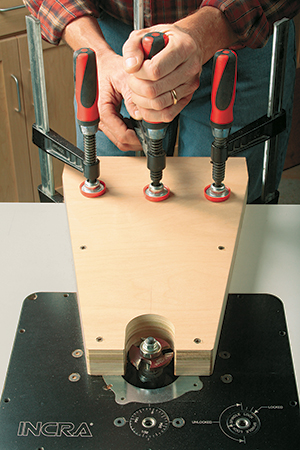

Before you can do some permanent assembly, make a slotted routing jig so you can cut the shallow mortises in the bed legs for metal connecting hardware. My jig consists of a top plate with a 3/4″-wide, 4-1⁄4″-long slot in the center and a fence screwed underneath for clamping. I was able to cut both the large mortises for the metal plates of this receiving hardware, plus deeper grooves for the hooked “prongs” of the mating hardware, using the same routing jig. For the shallow 1/8″ mortises, I outfitted my router with a 3/8″ O.D. guide collar and a 5/16″ straight bit; I cut the deeper prong slots into these mortises without repositioning the jig by switching to a 3/4″-diameter O.D. collar and a 1/4″ straight bit.

With this done, ease the edges of all the bed parts with a 1/8″-roundover bit in a trim router, but stop just short of where the stiles fit into the bottom rails and where the tops of the legs will fit into the top rails. Sand everything up through the grits to 220, and go ahead and glue the stiles into the bottom rails.

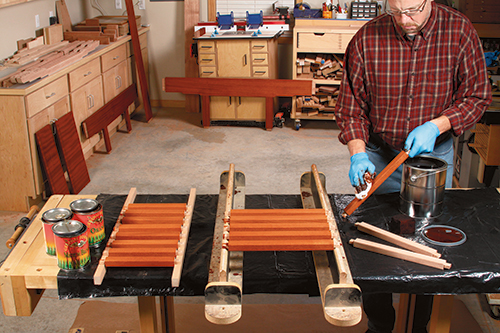

To approximate the color of many original Greene and Greene pieces, I followed a finishing recipe recommended by Darrell Peart, a published expert who specializes in this style. He mixes seven parts orange water-based dye with four parts medium brown dye to produce a beautiful, warm brown tone. Raise the grain of the bed parts before staining by wiping them down with water. Knock off any roughness and raised fibers after the wood dries with 320-grit sandpaper. Then flood dye onto the rail/stile assemblies, slats and panels, and wipe off all the excess immediately. Go ahead and topcoat these parts, too. I applied three coats of General Finishes Enduro water-based satin varnish.

When the finish dries, glue up the complete footboard and headboard with the slats and panels installed. The reason not to pre-finish the legs and top rails is so you can scrape and sand their corner joints flat now, when these assemblies come out of the clamps. Once that’s done, dye and varnish this bare wood.

Making the Side Rails

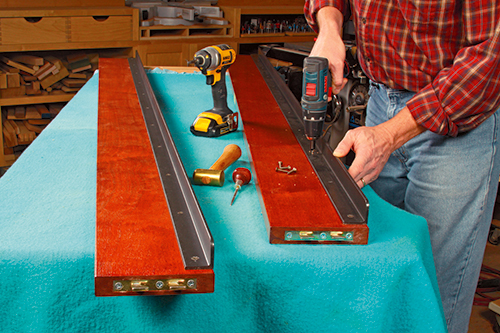

The side rails begin as two long planks of 1-1⁄8″-thick lumber with bed rail mortises cut into their ends. My handy slotted routing jig worked here, too. I just tacked a 1/4″-thick spacer to the fence to offset it for centering the jig correctly. A 3/8″ guide collar and 5/16″ straight bit took care of the mortising work again. Cut these mortises 3/16″ deep instead of 1/8″, so the pronged hooks will pull the side rails tightly against the headboard and footboard once assembled. Stain and topcoat the rails, then fasten the hooked connectors with #10 x 3″ flathead wood screws. Attach the headboard and footboard hardware with #10 x 1-1⁄4″ screws.

The bed’s box spring rests on two lengths of 1-1⁄2″ x 1-1⁄2″ angle iron, positioned flush with the bottom edges of the side rails. Prepare the irons by drilling eight to 10 counterbored holes for #10 x 1″ flathead wood screws, then cleaning the metal and spray painting them a dark color. Fasten the irons to the rails.

Adding the Signature Square Wood Plugs

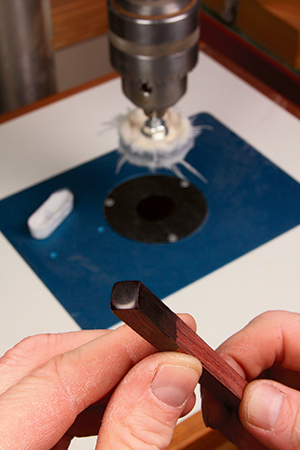

Pillow-topped wood plugs, made from a darker hardwood, are classic Greene & Greene details wherever two parts intersect at a joint. I made 5/16″-square plugs for the “major” joints (leg/rail, stile/rail) and used 1/4″-square plugs for the slats and on either side of the larger plugs on the bottom rails.

The pillowing effect was easy to do by spinning the ends of my plug “sticks” in a drill/driver against sandpaper of various grits.

The hardwood I chose for the plugs — an ebony alternative called katalpa — wasn’t dark enough, so I dyed the plugs black and sprayed them with satin lacquer.

After several hours of pounding and drilling each of the bed’s 56 plug mortises 3/8″ deep, I glued in the plugs. All that was left was to fabricate a half dozen pine slats to span between the irons.

Jo Ellen and her husband Rick are pleased with the style and sturdiness of their new bed. I’m sure the recipient of your Greene and Greene masterpiece will love it, too.

Click Here to download a PDF of the related drawings and Materials List.

Hard to Find Hardware

4″ Bed Rail Fasteners #28589