A few decades ago, Gerald “Jerry”Curry was working as a carpenter, doing framework on new houses and renovations on old ones. Seeing the quality of work on the older ones, he said, made him gravitate to older things as better made.

So, when he decided to make some furniture, it wasn’t too surprising that he went looking for something “old style.” In his case, that first piece of furniture was a Philadelphia style Chippendale lowboy, modeled after the type of furniture found in displays at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

“It wasn’t a style I really loved,” Jerry said, but he wanted to challenge himself — and to show potential customers that, if he could make something particularly complicated, then surely he could make something simple as well. Also, “It was the mid-1970s, so there was the Bicentennial hoopla. People were a little more interested in old furniture.”

Jerry put together a small catalog of about 10 pieces he could make and started advertising in the back of Antiques magazine. “Slowly but surely, I got enough work to keep me going,” he said, and by about 1985, he had a backlog of about two years’ worth of work.

He taught himself the skills to do that work, including a copy of a Queen Anne style 18th century highboy that included “a lot of carving, gilding, veneering, French polishing, inlay — it challenged me in a whole bunch ofways. I just did it. I just winged it.” Prior to taking his business in the furniture building direction, Jerry had built a few items of furniture for himself, but “they looked like a carpenter made them: just terrible,” he said. “I have since cut them up and put them in my woodstove.”

With his focus on furniture inspired by 18th and 19th century style furniture, Jerry said, “I do have an interest in history, especially American history, as it dovetails with furniture — but all I do is read a bunch of David McCullough’s books every now and then.”

His business, however, has moved from making new furniture, albeit in old styles, to mostly fixing actual antique furniture. “For me, new furniture’s pretty much dead,” Jerry said. “It used to be 90 percent new furniture and 10 percent repairs; now it’s switched around. Since about three to five years ago, I now mostly do repairs for antique dealers.”

Partly, Jerry said, there are more people making furniture now, so it’s an issue of supply and demand. There are other factors he cites, too: “Everyone’s internal price computer has been reset by Walmart. If you say, ‘I’ll make you a coffee table for $800, people aren’t willing to pay that.'” Also, he thinks that the current furniture world is more design-driven than it was in the past. “Even antique dealers like modern furniture. They don’t want reproductions, because they think of it as ‘not culturally true.’ It was made ‘out of period,’ so it’s not reflecting the culture of the maker.”

Still, since he made “pretty accurate reproductions” of furniture in the styles of the 18th and early 19th centuries for so long, it’s helpful in doing the repairs on antiques. “There are often parts missing, and you have to know what it should look like,” Jerry said. While he has seen the hinges broken off more than one card table with a top designed to open up, for the most part, there are no “common” repairs, Jerry said. “It’s often not just wood, but fabricating some metal parts as well. Sometimes there’s inlay involved. There’s almost never something I do when I fix something that I do it again. There almost always seems to be something new.”

In doing those repairs, Jerry does a little bit of finishing, mostly matching colors if, for example, there’s a chunk of wood missing from the top that he needs to replace. “The darker the wood, the easier it is to match, because you can add more color. Lighter colored woods are harder to match,” Jerry says. “Thankfully, most old finishes are often thick and muddy.”

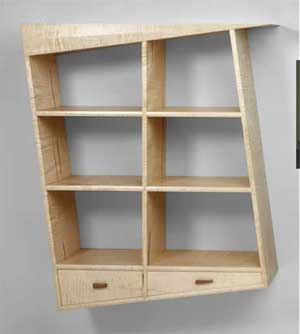

As for woods, when he’s actually building furniture, Jerry said he used to use a lot of mahogany, but now he finds himself mostly working with cherry, walnut and maple, particularly curly maple. Part of it is due to availability, part to his finding today’s mahogany softer than it used to be, and part due to customer demand. “Mahogany by its nature seems formal, high style,” Jerry said. “Most customers want something a little less formal.”

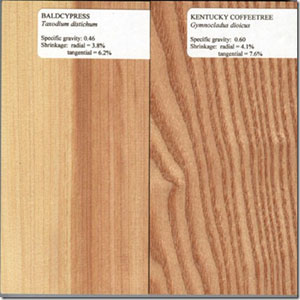

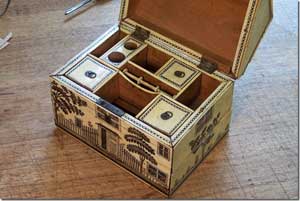

“American woods have always interested me,” Jerry said, and these days, when he has a slow time in his shop, he has been making sets of wood samples that he sells through Lie-Nielsen Toolworks. The sample sets include 1/2-inch thick, 3-inch wide, 6-inch long samples of 46 different kinds of American woods, labeled with the species’ common and scientific names, as well as their density and both longitudinal and radial shrinkage. The box containing them includes directions for calculating the shrinkage and expansion of different species.

As for his repair work, while he enjoys the challenges of frequently facing new problems, other than occasional pieces, he doesn’t find the things he works on particularly memorable. One exception was an ivory sewing box made in India. “It’s sort of like scrimshaw: they scratched the ivory and put ink in. That was a piece that stood out, because I don’t do much ivory.”

Otherwise, Jerry said, “Sometimes I’ll talk to antique dealers and they’ll say, ‘Remember that card table you fixed for me three or four months ago?’ and I don’t remember it. Once they leave my shop, they’re gone.”