A self-closing chuck is alluring because it offers no-hassle, vice-like grabbing of anything you want to turn … at least, that is the advertising claim!

A chuck is anything that holds work in the lathe, so a drive center, a live center or a faceplate are all chucks — and most lathes come with this useful trio. Simple spindle turning needs only the aforementioned drive and live center; however, they are insufficient for hollowing in spindle orientation. While it is possible to turn a bowl by just screwing a piece of wood to a faceplate, turning the outside of the bowl is awkward, and much depth in the finished vessel is lost to the screws. A glue block can overcome this problem.

Still, a self-closing chuck is alluring because it offers no- hassle, vice-like grabbing of anything you want to turn. At least, that is the advertising claim. This is all to say that what is properly called a scroll chuck is an easy sale to a turner — whether novice or seasoned veteran — walking into a woodworking supply store. One of the most frequent questions I am asked is, “What brand/model of chuck should I buy?” This places me squarely on the horns of a dilemma, because a four-jaw scroll chuck is a very useful accoutrement for a seasoned turner. A beginner, however, will have a good deal of difficulty getting one to perform as advertised and may actually throw more work off of the lathe than with faceplates and glue blocks.

My aim in this article is to acquaint the reader with the desirable features to look for in a scroll chuck, and to detail the fine points of the basic holds you can accomplish with it, to lead to sure gripping of the work.

In metalworking, the use of a lathe chuck with jaws (sometimes called dogs) that close in unison to grip a workpiece is old hat. In my youth, I purchased a four-jaw metalworking chuck to quickly hold square pieces. Although useful, the problem with such chucks is that the jaws are designed for metal so they mar wood egregiously. So it was a marketing tour de force in 1988 when Teknatool under the brand name Nova introduced an economical four-jaw scroll chuck with top jaws specially designed for the needs of woodturning.

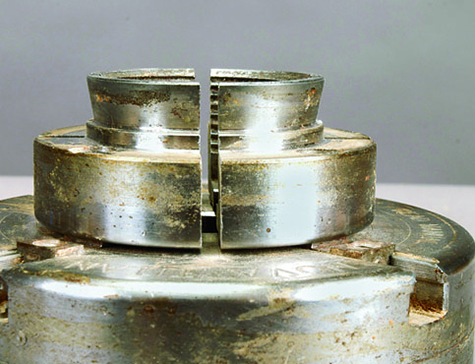

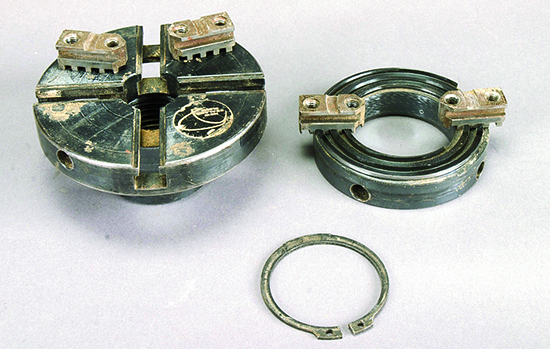

Now variously called engineering or scroll chucks, the jaws of these are usually of two pieces. The bottom jaw has a rack on the bottom and fits snugly in a T-shaped radial keyway in the chuck body. A scroll plate engages the racks on the bottom side of the jaws. Turning the scroll opens or closes the jaws simultaneously. The top jaw interlocks with the bottom jaw and is further secured to it with socket head cap screws. This scheme allows the top jaw to be changed to different shapes for specialized holds. The crucial factor is that the jaws have much larger surface area for holding wood securely without deforming it. Nova’s initial chuck was a lever chuck.

In 1994, Oneway in Stratford, Ontario, introduced a superb gear-driven chuck called the Stronghold. In 1997, they started producing a smaller gear-driven chuck called the Talon. In a gear-driven chuck, the bottom side of the scroll is a bevel gear, which is engaged by a mating bevel gear either enclosed in the chuck itself or on the end of a T-handle, allowing greater closing force to be applied by the jaws, resulting in surer holds.

While lever chucks are still offered, a gear-driven chuck is much more desirable. The Australian firm Vicmarc offers a line of high-grade chucks well worth your consideration. Vicmarc’s VM150 Chuck will work as either a lever or a gear chuck, making large adjustments with a lever, while final tightening is gear-driven. Penn State Industries offers both an inexpensive lever and a gear-driven scroll chuck under the name Barracuda. The Woodturners Catalog offers what appears to be the same chuck under the name Apprentice. Both companies offer the gear-drive chuck with an assortment of jaws in a basic package. While not up to the quality of the other chucks mentioned, they are quite serviceable for someone just getting into turning with a small lathe. In general, most of the scroll chucks on the market perform the tasks reasonably well.

A safety concern with scroll chucks is that, at some point as you open the jaws, they lose their engagement with the scroll and may be pulled out of the keyways with your fingers. If you lose the engagement with one or more jaws and start the lathe, a very dangerous ballistic event will occur. An ironbound rule is that you never extend the jaws more than one-third out of the chuck! Nova realized this danger from the beginning and designed their scroll to spiral in the opposite direction from all other chucks. That is because the forces of starting the lathe with a chuck on the spindle that is holding nothing will cause the chuck to close and not open.

Nova incorporated a further safety to their chuck: a stop screw that prevents the jaws from coming off of the scroll. Oneway does this same thing with a keyway. There are two keyways, with the shorter one not allowing the jaws to extend beyond the body of the chuck at all. This is a great feature for a young or beginning turner because they cannot be raked by the spinning jaws, which can leave a nasty wound.

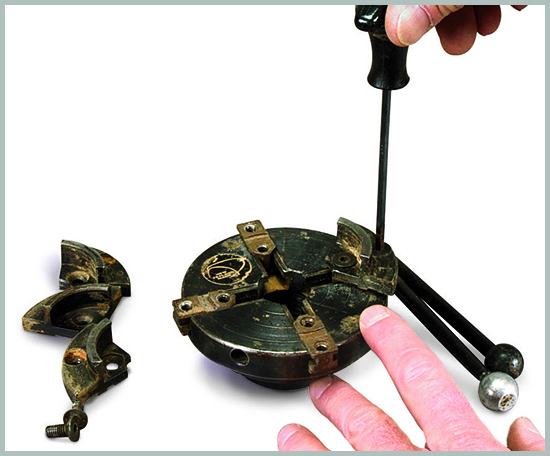

Disassembly should be part of regular maintenance to keep the chuck accurate. You will have to remove the safety screw, or the top jaws in the case of the Oneway. Remove the bottom jaws and even the scroll for a very dirty chuck. Brush everything off and reassemble. Coating everything with paste wax or a dry lubricant like Dri-Slide® greatly enhances performance. The jaws are numbered and have to be inserted and engaged by the scroll in numerical order. Once the chuck is reassembled, replace the safety screw or the top jaws and open it as far as possible. Now pull on each jaw and make sure they are engaged by the scroll. The jaws not centering is a sure indicator that the scroll did not grab them in order.

All chuck manufacturers offer a heavy screw in the 3/8″ to 1/2″ range. When the screw is gripped in the jaws, it converts the scroll chuck to a screw chuck, which is most useful to a bowl turner. To use these screws safely, you must be sure to have the head of the screw behind the top jaws and further ensure that the bottom jaws engage the flats on the head.

All manufacturers, except Oneway, put a back taper (dovetail shape, photo below) on the outside of their jaws. By grinding a scraper to a mirror image of this taper, you can scrape a dovetail-shaped pocket in the base of the bowl. The jaws will then expand into this dovetail, giving a sure hold that is less susceptible to being pulled off the chuck. Oneway has a double edge on the outside face of their jaws, which works best with a mortise with straight sides.