Most woodturners probably don’t think of the desert as a prime location for found wood, and that is exactly what David Crawford surmised when he moved in 2012 from timber-rich Pennsylvania to Phoenix, Arizona.

“I was struggling to find a reliable wood source until my wife suggested sending emails to all the tree-felling/ trimming companies in Phoenix,” explained David. “I sent 23 emails and received only one response. Since then, I’ve had a great working relationship with that particular tree trimmer.

“Once or twice a year, I give his wife a large bowl from the green wood he’s given me. I use other sources including fellow turners, craigslist.org (which has provided me with some great wood), friends, neighbors, and one or two company wood yards I’m able to access. The downed trees from the summer monsoons in July and August also provide a good resource as well as long as you can get to the wood before it is buried, burned, chipped for mulch or simply left to rot where it fell.”

David’s Process

David has a step-by-step process for harvesting and blanking his found wood. His first step is to try to be onsite when the crew is felling a tree so he can tell them how to cut the logs, depending on the relationship of length to diameter. For example, if the logs are 15-plus inches in diameter, he asks them to rip the sections in half. “I usually pay them (in cash) to do this and then load them in the back of my SUV. There’s nothing heavier than a two foot long, 15″-diameter piece of wet mesquite. I always wear a back wrap when I load and unload the wood.”

Once the wood is unloaded into David’s yard, he immediately covers the pieces with wood shavings and wets the pile with a garden hose. “I can keep wood for a week or two in a wet pile before it begins to crack. If I am going to turn a piece immediately, I move it into my woodshop.”

When he’s ready to turn a piece of stored wood, David selects the log he wants and marks the log’s pith on both ends to determine where to rip the log for the best result.

David’s cutting platform consists of two logs side by side. He centers his cut through the pith to split the log section into two halves.

After scribing the top of each halfsection with a compass, David highlights the pencil line with a dark marker.

He chainsaws the log into a rough circle, making taper cuts to what will be the bottom of a bowl.

After moving the trimmed blank into the workshop, he attaches a faceplate ring to the flat surface. This will be the top of the bowl. The faceplate ring is secured to the chuck, with the tailstock moved into position to support the opposite end.

David typically starts his turnings at a speed of about 250 to 300 rpm, making sure the lathe doesn’t vibrate or shake excessively as he turns the blank round. He always wears a full-face shield and a leather glove on his left hand — getting a large blank round is tough on the hands, wrists, arms and shoulders.

As the wood comes into round, he increases the speed. First he completes the outside shape, then he flattens the bottom in preparation for cutting the spigot/tenon for a four-jaw chuck. The spigot must be cut carefully to fit snugly into the chuck and be seated properly.

After reversing the blank on the lathe, David removes the screws from the faceplate ring. He trues the face of the blank and cuts a small dimple in its center to seat a 12″-long drill bit — using one of his granddaughter’s hairbands for a visual guide. He pushes the handheld drill bit into the blank to the desired depth of the inside of the rough turned bowl.

As he turns the inside of the bowl, wall thickness will vary dependent upon wood species, but David usually turns his pieces down to about 1-1/2″.

He uses Anchorseal® to seal the inside and outside of the bowl, dates it with a marker, and places it on a shelf to dry. Depending on the wood species, David checks the bowl daily or weekly for checks or cracks, using cyanoacrylate (CA) glue to fill them. When the blank measures 6 to 8% moisture content, he will finish turn it.

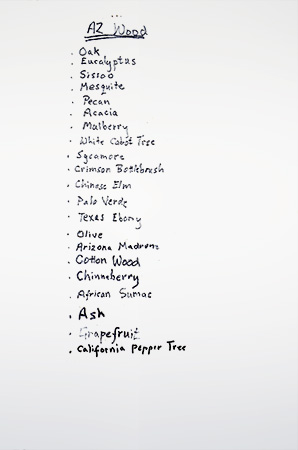

Since his move to Arizona a few years ago, David Crawford has kept track of the species of wood he’s found and used in his new home.

To read more about David’s assessment of his favorite (and least favorite) Arizona woods, Click Here.