What’s the shelf life of your favorite finish? Is there a way to store it that increases shelf life? How do I know when it’s time to bite the bullet and toss it? And finally, how do I legally and safely discard old finish?

Shelf Life

Manufacturers typically suggest a shelf life of three years for most finishes, assuming they are stored correctly. That includes both aerosol and regular cans of water-based clears, paint, oil-based varnish, polyurethane, Danish oil, gel urethane, wiping varnish, lacquer and even two-part conversion varnish, provided the reactive agent is stored separately. In reality, you can often use much older material, but this is still a good “use by” guideline. It helps to write the date of purchase on cans that you buy to keep track of their age.

Shellac is different in that it depends on the cut. A five pound cut (very thick) will last three years, but what you probably use, a two pound cut or thinner, will only last about six months, even if unopened. The exception is Zinsser® SealCoat™, made from a long shelf life shellac resin that will last five years.

“Pre-cat” lacquer, which is modified conversion varnish with the reactant already added, will have a much shorter shelf life, depending on the type and amount of reactant that was added. Follow the manufacturer’s suggestions, but I’ve seen “pre-cat” lacquers with shelf lives as short as six weeks and as long as a year.

There are two notable exceptions. Clear nitrocellulose lacquer will usually be fine even after a decade or two, provided the can is airtight. Ditto for clear gloss oil varnish, though not for satin or tinted varnish.

Cyanoacrylate, a moisture initiated adhesive that some folks use as a finish, sealer or pore filler, will be good for at least one year if stored unopened in the refrigerator, but don’t freeze it. Once open, store it dry and at room temperature, but don’t wipe the tip or touch the tip to the work, either of which can cause clogging. It’s usually good as long as it is still liquid.

Store for Longevity

Make sure water-based paint and clear finish are well sealed in an airtight container, and store in a cool, dry place in the shop. It’s best to press can lids on with pressure around the rim. Hitting the center of a lid can warp it so it won’t seal properly. For screw-on lids, clean the lid and spout with the finish solvent, then wipe a bit of Vaseline® on the threads, or drape the spout with a sheet of waxed paper, parchment or plastic wrap so the lid doesn’t get glued on.

Oil-based finishes, like varnish, polyurethane, wiping varnish and gel urethane, will crust and even completely cure if there is air (oxygen) in the headroom, which is the area between the lid and the top of the finish. The more you use, the more headroom. Eliminate the headroom by adding marbles or stones to raise the liquid level, creating a barrier between air and finish with plastic or an isolating liquid, or replacing the oxygen with inert gas before sealing the lid.

Testing Old Finish

To test your old finish for viability, first, look at it. If it was meant to be a liquid and is now thick, crusted or separated, it’s best to discard it. Ditto for anything moldy or with a different than normal odor.

Paint, for instance, will separate into what looks like a substantial layer of clear water and a mess of pigment and resin below that looks a bit like cottage cheese. That’s a good sign it’s past its prime. Shellac deteriorates very quickly, so I’d test any shellac more than six months old. Lacquer, as usual, is an exception. Even lacquer that has gotten thicker can usually be saved by simply adding more lacquer thinner.

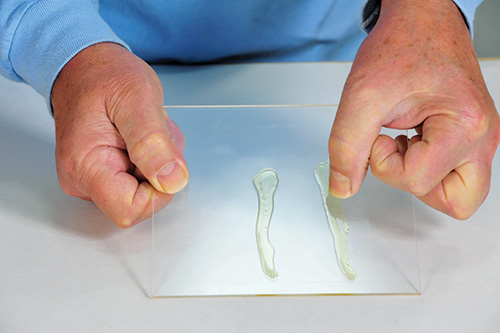

When in doubt, test it. Spread a drop or two onto a piece of glass or laminate. See if it cures solid in the time it is supposed to, and press a thumbnail into the cured finish to ensure it is solidifying sufficiently. It’s even better if you can do a comparison test: a drop of the finish in question next to a drop from a new can of the same material. If it’s viable, the old should dry as fast and as hard as the new. Finishes vary, but a good rule of thumb is that a normal coat of shellac or lacquer should dry to the touch in well under an hour, latex paint in two hours, and oil-based varnish overnight.

4 Ways to Remove the Headroom

“Headroom,” in finish storage, is the area between the lid and the top of the finish. Oxygen is the enemy here: its presence will cause a crust to form on your oil-based finishes, eventually causing all of the contents to harden. As you use more finish from the container, you get more headroom where oxygen could do its dirty work. What’s a woodworker to do? Here are a few solutions.

Throw it Out

Throwing away finish is not as easy as tossing out wood scraps. Liquid finish is not safe for landfills, as the solvents in it can leach into the soil and contaminate the water table. In most cases, it’s also bad news for sewer systems.

That leaves two options. If the finish will still cure (is viable, but no longer needed) you can brush it ALL out onto cardboard or scrap wood. Once it is cured, it is inert and therefore landfill safe. Viable water-based paint can also be reused/recycled at places like Habitat for Humanity and some local recycling facilities. Check in your area to see if that’s an option.

The other option, and the only one for finish that will not cure, is to find a place locally that accepts old finish. Because the rules vary so much from area to area, you’re not likely to find reliable information on a national scale. My local transfer station (the former landfill), for instance, accepts both water- and oil-based paints. Bear in mind that, unlike latex paint, oil-based and solvent-based coatings are considered hazardous waste.

Check with the folks who collect your trash — they’ll often know how to legally dispose of coatings — or do a search online for “hazardous waste disposal” in your city or area. A search for my town brought up the county recycling center contact information as well as several companies who collect hazardous waste for a fee.