If you’re a woodturner, you’ve likely heard the name Ernie Conover. He — along with his dad, Ernest Conover Jr. (Ernie’s number III) — is one of the inventors of the Conover Lathe. He’s also a founder of the American Association ofWoodturners, and coordinator of its first symposium. Plus, these days, he’s the regularly featured writer in the Woodturning department of the print edition of Woodworker’s Journal.

Ernie got into turning originally “mainly doing parts for my general woodworking — chair legs and such.” He’d come from a background of making his own tools, partly because new ones were unavailable, partly because they were unaffordable. And, while he and his dad had previously purchased old lathes to restore, they decided to make a woodworking lathe “because we didn’t like the ones we could buy.”

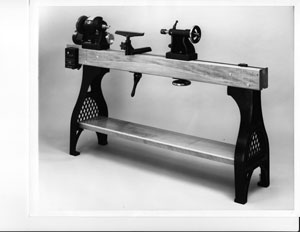

Ernie’s dad was primarily a metalworker, and Ernie himself is trained as both a woodworker and a metalworker, and they were aware, Ernie said, that “up until about World War II, in England, could buy a lathe and add a headstock and a tailstock.” All of this led to their creation of the 16″ Conover Lathe, for which the end user supplied a bed made from 2″ x 6″ lumber.

Although the Conover Lathe is no longer manufactured, it does factor in to how Ernie got into woodturning education. In addition to the lathes, he was designing other woodworking tools, as well. Mike Dunbar (founder of The Windsor Institute) convinced him to offer courses to teach people how to use the tools.

Those early summer courses have grown into today’s Conover Workshops, which offers scheduled courses, private lessons and apprenticeship opportunities. This month, Ernie was in the midst of teaching a Hand Tool Joinery workshop, “which starts with the willing suspension of disbelief: that machine tools do not exist.” For the first day of the course, Ernie also dresses in 18th century attire and has the students sign an indenture contract from that time period.

“I’ve always been a tremendous history buff,” Ernie said, which shows up not only in his classroom, but in his projects, books and tool collection, as well. A collector of antique tools, all of which are in good working order, he says, “I don’t know if I like using ’em or collecting ’em more.” Ernie’s collection includes a full range of hand planes, from 1 to 8, as well as a Boice-Crane band saw and a South Bend metalworking lathe. “I use many of ’em every day,” he said of his antique tools. “It brings me a great deal of pleasure.”

He’s also proud of including information in his nine books that is “something I felt was valuable now, and valuable for posterity.” Particularly in his book The Frugal Woodturner, Ernie said, “I set down a lot of things about lathes that I think could be lost with the drive to turnkey.” For instance, he said, “jam chucking: you turn a pocket in a piece of wood, and tap a piece into it. Until you can use a faceplate and a set of centers, you have no business using a commercial chuck.”

“I’m also extremely proud of The Woodworker’s Guide to Dovetails,” another of his books, Ernie said. It covers both machine and hand tool dovetail joinery, since, he noted, “Both are valid. If I were going to build a kitchen, I’d get a dovetail jig out. On the other hand, if I was going to build a highboy, I’d probably hand cut them.”

Ernie has, indeed, “made a lot of complicated stuff” with his turnings, he said. For instance, he made a complicated spinning wheel for his wife, in the style of the 19th century great wheel version ofspinning wheels. Ernie’s wife is a weaver, as was his mother, and it was in making threaded parts for them that he first became involved in designing woodworking tools — the threaded tools were useful for woodworkers, too. The spinning wheel, Ernie said, “had 40 to 50 turnings in it by the time it was done. That was an awful lot of fun.”

He also turned 65 balusters and 10 newel posts for a spiral staircase in his home, and created 8′ x 3″ bedposts from true 4x4s for a Sheraton style bed. “I’ve had some sculptural fun, too,” Ernie said.

“One of my messages is ‘You never regret buying good tools, but they aren’t everything,'” Ernie said. “It’s like buying a piano: if you don’t practice, you’re never going to get anywhere, so spending some time in the shop is good, too.”