Innovations in woodworking widgets don’t always come from the research and development departments of big tool companies. Their inspiration sometimes springs from unlikely sources and when they’re least expected. For example, back in the mid 1990s, David Osborne didn’t consider himself to be an inventor, and he sure didn’t see his invention coming. Yet in a flash, the lightbulb of possibility suddenly burned brightly.

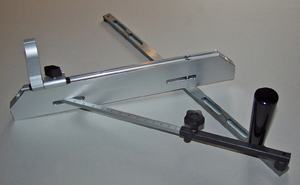

“My (product) idea came to me in about five seconds,” says the inventor of the Osborne EB-3 Miter Guide. It’s a triangulated miter gauge that uses a telescoping arm to set and lock miter angles easily, precisely and ruggedly. Available for more than 15 years now, it continues to be the biggest departure from the ubiquitous protractor-style miter gauges that come with table saws and some band saws.

Looking back, David is certain that his “Eureka!” moment couldn’t have come at a better time. Around 1995, he was living in Williamsport, Pennsylvania, working as a patternmaker for the foundry industry. While the job provided manufacturing experience and the chance to do precision woodworking, “I was in my mid 40’s and making an hourly wage but watching most of it ending up in the pockets of the guys that ran the business,” Osborne recounts. Job frustration was an understatement. “Every single day for the last few years there, I would grind my teeth all day long thinking, there’s got to be a better way.”

Osborne dreamed of breaking out on his own, developing some new product that would finally help him achieve financial independence. He considered dozens of possibilities but all of them eventually presented roadblocks he couldn’t practically overcome. Up to that point, he says, he had never invented anything else.

But everything changed without warning one day during a visit to Grizzly Industrial’s Williamsport showroom. Osborne was standing in the middle of dozens of table saw models and asked a store manager if customers ever requested a woodworking product that Grizzly didn’t carry. “Not really” was the reply, David recalls, “but he said it would be nice to have a decent miter gauge.”

Glancing around at the miter gauge options, David realized that the real design deficiency is their instability at the outboard end of the fence. On a protractor-style gauge, the longer the fence, the more likely it is to flex at the outer end. And, the small size of the protractor scale makes it difficult to set angle cuts accurately. A telescoping diagonal brace would be a better way to stabilize the device than a smaller pivoting head, Osborne reasoned, and essentially it would form a triangle with an adjustable hypotenuse. The brace’s linear shape would serve as a more precise means of setting and locking angles than a half-round scale.

“It was a five-second thought process where all the questions answered themselves with simple logic. That basic design was the easiest part of the entire process to date,” Osborne says.

Turning that moment of pure inspiration into a marketable woodworking product would take three years of hard work, tremendous financial risk and “a million ways to go wrong,” Osborne says. Starting in 1996, first with cardboard and wood, then with a pile of metal supplies and Bondo® from his local Lowe’s® store, David built prototypes of his miter guide. He also started searching through patent history to see if similar ideas had already been patented and if his concept was worth pursing further.

When David developed a working prototype, he took it to the local chamber of commerce to see if the product’s uniqueness would qualify him to participate in Penn State’s Ben Franklin Technology Partners (BFTP) program for entrepreneurs. It did. Over the next two years, BFTP provided Osborne access to business networks, a variety of expert resources and grant funding. He sought the help of a patent attorney to apply for a patent, but receiving patent approval took two attempts, almost a year of time and $12,000 from Osborne’s bank account.

Then came the process of starting up manufacturing, which David sums up as a “massive task fraught with numerous ways to screw things up.” It seemed like walking on the razor’s edge, and success or failure would be determined by a myriad of decisions. What materials and manufacturing methods would be most effective? Should the miter guide be fully featured or kept simple? What business model would have the best chance of succeeding? Who would be the right people to work with?

On top of that, there were substantial costs involved. David mortgaged his house to come up with sufficient funds to buy five extrusion dies for the various aluminum profiles his miter guide would need. He had to buy thousands of pounds of extrusions, specialized fasteners, steel bar stock, knobs, handles, bolts and boxes in order to make the per-unit cost for the miter guide affordable. He also refurbished a small building to serve as a workspace and warehouse where he assembled, tested and packaged each miter guide in order to keep his overhead to a minimum. For the first three years, Osborne recalls, “I was a one-man show.”

His biggest fear, early on, was that he had too many subcontractors responsible for the various aspects of manufacturing — everything from raw materials to packaging supplies to custom fabrication was outsourced, and it would only take the failure of one of these sources to potentially shut his operation down. The prospect was frightening, David admits, and “I was the one in control but in a practical sense, I had no control at all.”

Still, a better “mousetrap” in the woodworking community will get noticed if the right contacts see it, and David was counting on it. Once he had inventory, he needed customers but didn’t have the money for advertising. So, Osborne tried an unorthodox approach to gain some industry attention: stealth. “In ’97 I decided to go to the AWFS (Association of Woodworking and Furnishings Suppliers) show in Atlanta. I couldn’t afford a booth, so I carried a miter guide into the show hidden under my overcoat.”

Once he got past security, he showed his newfangled EB-3 Miter Guide to many dealers and distributors, along with key woodworking magazine editors who were in attendance. David recalls that most who saw his new design had a “Why didn’t I think of that?” response, and it was the validation he needed. By the end of the show, a dozen distributors and five national woodworking magazines were convinced that Osborne had a breakthrough innovation in miter gauges, “and I was on my way.”

It also helped when “New Yankee Workshop’s” Norm Abram got on board. Osborne says Abram first thought the EB-3 was just an angle-setting device instead of a new form of miter gauge. But once Abram tried it out, he started using it on the show and it was made available through the show’s website.”He could use any tool he wanted and he chose the EB-3 over any of the 20 or so aftermarket guides … that was more validation for me,” Osborne says. It was also a windfall of consumer attention. “Later on, many customers would comment, ‘If it’s good enough for Norm, it’s good enough for me.'”

Since then, there have been licensing agreements for the EB-3 with several industry leaders. Black and Decker signed a deal with Osborne in 1999 to include an updated version of the EB-3 on a DeWALT-branded table saw. That association ended in 2005. In 2006, General International began to produce the Osborne EB-3 within its Excalibur tool line and served as its primary distributor, but that agreement expired last year. David now has established production of the EB-3 independently in Taiwan and has become his miter guide’s exclusive supplier once again. Osborne is also handling all warranty and customer service issues related to the EB-3s past and present. “I guarantee that I will keep the EB-3 working for the life of the original owner,” he says. This year, he hopes to reestablish exclusive relationships with previous dealers, and he sees the end of the licensing period as an opportunity to relaunch the Osborne Manufacturing brand again.

While the uncertainties and challenges of an intrepid inventor may never go away, Osborne is confident he would absolutely do it all over if he had to. “Has it been hard? Yes. Have I second-guessed myself? Yes. I have suffered some big setbacks, but there is a reward an entrepreneur gets from being directly responsible for his or her own success or failure that is not present when you are working to achieve someone else’s dreams.”

For those out there who might like to invent something new for woodworking, he offers some kernels of wisdom:

• Focus on something that fills an existing need. Don’t just build another toaster, because you will be competing in a saturated market. What is a need that has not been addressed?

• Talk to people in the industry to find out if anyone else shares your enthusiasm for your gizmo.

• Diligently follow a (logical development) process until you reach or foresee an unsolvable problem. If it’s too hard or risky, drop it. Try the next thing. The thing that works might not be related to your interest. It may not be a tool.

• A product that addresses a small problem for masses of people is better than a massive undertaking that appeals to a limited group of consumers.

• Don’t be intimidated by the unknown. Have belief in yourself, that you can do the research and make the decisions that can take you where you want to go.

To learn more about the Osborne EB-3 Miter Guide, click here. To follow Osborne Manufacturing on Facebook, click here.