Some of us get our first taste of woodworking at a late stage in life, but furniture maker and designer David Hurwitz was luckier. He got his start at the same time he started school.

“In first grade, at the age of six, I learned how to use hand tools,” David recounted. “That was because I went to an alternative elementary school run by the New York state university system, and it had a woodshop available for students from first grade onward. By the time I was nine, I had learned how to draw as well as build, and was soon creating three view drafting.

“I also took woodshop in high school, went to RIT (Rochester Institute of Technology) for mechanical engineering, then switched to their four-year woodworking design program, the one started by Tage Frid before he moved to RISD (Rhode Island School of Design.) During summers I worked in high-end cabinet and architectural woodworking shops. I graduated from RIT with a degree in fine arts focusing on woodworking, furniture design and sculpture. About a year after leaving school, in 1993, I started my own shop.” That shop still exists today.

“For the first few years, I did high-end built-in wall units,” explained David, “but gradually I switched over to doing mostly hardwood freestanding furniture. At this point, everything I build is my own design. Some pieces are speculative, often for galleries, and others are commissioned. At present, about half is commissioned work, but I am now leaning more toward speculative work, thanks in large part to the Internet.”

That fact that he enjoys design challenges is evident in the range of styles he creates. “The wine cabinet is one of my favorite furniture pieces because it offered a number of challenges, including bent plywood and veneering. I like Elroy [pictured at top of page], too, because the challenge was to create a piece I could build in one day that would come apart and ship flat in two boxes.”

David doesn’t just do furniture. His web site also features some interesting accessories, like wooden kitchen utensils. “I actually made my first utensils as a student in college, largely as a way to practice carving, and as a break from large intensive pieces. There’s instant gratification that you get from a piece you can make in an hour. Utensils also provide gifts for people when you don’t have money to buy them things, and of course, spoons and spatulas are a great way to use up scrap wood from the larger pieces.

“Along the way, these took on a life of their own because utensils fit into a gift or craft market which has many more sales venues than furniture. I could easily have made that my sole focus, but furniture is what it is really all about for me. Typically, I spend about a month per year making utensils, and the rest of the time doing furniture.

“Around 1997, I started making lamps, then added mirrors around the end of the century. With lamps, I play around with how light works with the sculptural aspects of the wood I am forming. Making the shades of handmade paper and vellum brings in another medium to work with that complements the wood. Illuminating the natural textures adds yet another dimension of design.

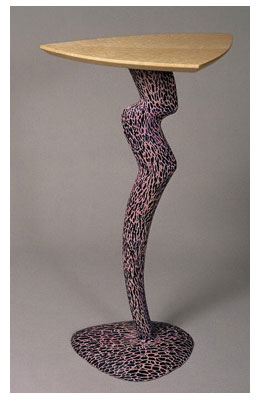

“Textures are an important element of sculpture that I like to bring into my work. Some pieces, like this hall table, use both carving textures and paint to create contrast and interest. Playing around with layers of contrasting colors of paint and carved textures yielded this plant stand.” That mix of paint and texture shows up again on his evocative poodle table.

“With mirrors, it is the concept of reflection that appeals to me. When I sculpt the frame, I create an undercut so part of the frame is protruding out over the glass and thus reflected in it. In some cases, this lets you see both sides of the frame at once. One frame sports a semi-circular shelf that hugs the glass, making it look as if the shelf is a complete circle. Some of the frames undulate like pulled taffy, and are named for just that characteristic. I wanted to have the look of the wood being physically twisted and bent when in fact it is actually just carved.

“I also do pure art sculpture,” David admitted, “but I don’t sell it or post it on the web site. I have been thinking about starting to show it, but most people in the furniture and craft world expect function as an aspect of what they buy. Most of my sculptural pieces are carved abstract freestanding or wal- hung works. I may build up a body of work and find the right gallery and show one of these days, but all that takes time, and I work alone.”

Working alone can be a double-edged sword. “When you work alone, you sometimes feel you are working in a vacuum, and having others around is inspirational,” David pointed out. “Part of why I moved to Vermont was to be around other artists. Working alone provides not only the challenge of inspiring yourself, but also that you have to both build and market your work. I would prefer to just build.

“What drives me and is most important to me is working with my hands and making things. I like to keep things fresh, so I avoid production mode and focus more on individual pieces. A high level of quality and a respect for the materials are important to me. I tend to be a perfectionist and sometimes have to rein that in to be able to make a living. These days, I focus my perfectionism on those areas where it matters.”

Apparently, he has done a good job of it, because in addition to running a successful business he has managed to garner quite a few awards for his work. He took first place in last year’s Vermont Fine Furniture and Wood Products design competition for his utensils, and both a Member’s Choice Award and a second prize award at Around The Looking Glass: an exhibition of framed mirrors selected from the museum’s tenth annual thematic competition for artists working in wood at The Wharton Esherick Museum, Paoli, Pennsylvania in 2003. He is also the recipient of the 1991 Kearse Award from the College of Liberal Arts, Rochester Institute of Technology, Rochester, New York, and the Design Creativity Award from the 1990 Design Emphasis ’90 / Student Furniture Design Competition at the International Woodworking Fair in Atlanta, Georgia.

The awards are mute testimony not only to David’s woodworking talent, but also to his creativity and love of challenge. Still, the bottom line, aptly reflected in this advice he offers to fellow woodworkers, is enjoyment.

“Keep it fun,” he admonishes. “Whether you are professional or amateur, it should be fun. It should be an adventure. Stay open to new ideas and techniques, because there is always more to learn.”