Adrienne Dymesich and her husband Isac could have never guessed that a burned spatula years ago would lead them into forming a successful wooden utensil business. Maybe it was a fortunate accident, but after speaking with Adrienne, I think it has more to do with two “compulsively creative” Wisconsinites that take an organic approach to life. Their products, which range from spatulas, tongs, ladles and spoons to pie servers, soap dishes and cutting boards, all are handmade on the family’s 15-acre farm under the auspices of their shared business, “Carved for the Cook.”

Judging by their lifestyle, the building blocks for making sturdy, utilitarian but elegant kitchenware were already there. “I’ve always loved to cook from scratch, and that time in the kitchen has really contributed to the success of our business,” Adrienne admits. “We raise and grow a lot of our own food from a big garden and the cows, pigs, goats and chickens we keep. I try to cook healthfully and develop my own recipes for our family.”

Isac is a second-generation carpenter who runs a construction and remodeling business with his father and brother. Adrienne says the three men do everything from rough framing to finishing and installations, plus pretty much everything in between.

Now, more about that burned spatula, and how it all started.

“It was this really basic flat thing that I got as a bridal shower gift when we were married in 2003. I used it for about a year; before that I had never really thought about cooking with wood, but I grew to really like it … Then one day, I turned on the wrong burner by accident and scorched it.”

After scrapping the charred remains, Adrienne realized she could probably make a better replacement spatula than buying one. It helped that Isac had already taught her how to use a band saw. “I was dabbling in intarsia projects on the side anyway. How tough would it be to cut out a spatula?” she recalls. Not hard at all, as the story goes. Adrienne proceeded to make 30 or so more for family and friends, and Isac refined the design with a curvy handle. “That grip is what really sets our spatulas apart from others I’ve seen. They just feel so good in your hand, and that’s what really continues to appeal to our customers,” Adrienne says.

But there are other attractive features, too. Thoroughly kitchen-tested shapes, walnut or cherry wood options and choices of either right- or left-handed versions also help to usher these products into shoppers’ bags. Adrienne uses templates as a starting point for roughing out the basic form, but the final shape often changes as needed to better suit certain cookware or as the lumber dictates it. She takes full advantage of contrasts between heart- and sapwood and appealing grain patterns; those details make each piece distinctive and one-of-a-kind.

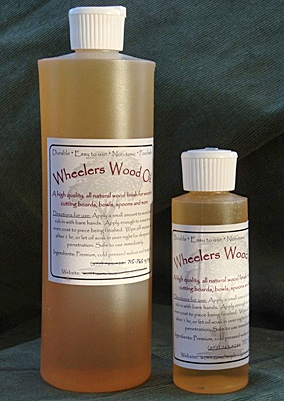

The progression from making wooden utensils for Christmas gifts to selling them at six to eight juried art fairs and craft shows each year didn’t happen overnight, or by accident. The Dymesichs credit that to their neighbor and mentor, Jon Wheeler. Wheeler is a trained woodworker and woodturner who, at the time, was selling his turnings and other wood products at various shows and farmers markets. Jon encouraged the couple to do the same thing and helped them strategize how to set up a successful booth and marketing approach. Wheeler also used and sold a walnut- and tung-oil polymerizing blend called Wheelers Wood Oil. It was a recipe John developed and tested on his own, and it was doing well with the woodturning and furniture-building crowd.

“We used Jon’s finish on our utensils right from the start, because our customers would consistently ask us, ‘Is the finish on your spatulas, spoons and so forth safe? Is it easy to apply, and will it wash off? How do I care for this?’ The finishing oil is not only safe when it’s cured and simple to apply by hand, but it also sheds water well and gives the wood a soft buttery glow. We think it’s key to selling our products.”

After a few successful shows, the couple began to upgrade their table saw, band saw and various sanding machines to professional-grade models, and mass production ensued. But, while Isac may have had more woodworking tool experience initially — he still does all of the routing aspects of their products — his work as a full-time carpenter limits his time for making utensils. Adrienne does most of the cutting, sanding and shaping stages, as well as inventory tracking and recordkeeping. Isac maintains the shop machinery and takes over the hand-tool work, gouging out spoons and ladles with a power grinding tool.

“We do our best to work ahead on inventory, making our various products in batches of 60 or so during the winter. But the workflow really varies, based on our family needs, ups and downs in the ‘show’ season and our many other interests. Sometimes I might spend four to five days per week in the shop; other times, less,” Adrienne says.

Several years ago, Wheeler decided to trade his woodworking apron in for a realtor’s license, so the Dymesichs bought his finishing oil business and the rights to continue selling Wheelers Wood Oil. They mix each batch themselves, fill the bottles and carry out the packaging duties. Adrienne also designed the label. Aside from using the blended finish, the couple sells Wheelers Wood Oil as an independent product with its own website. “Woodworkers have tried it on all sorts of projects, from turnings to knife handles and furniture. It adapts so well to almost anything made out of wood, and people like the fact that you can put it on with your hands.”

Adrienne and Isac try to add one new utensil or other wood product to their line every year, in order to give repeat customers new options. Still, each and every Carved for the Cook product is made by hand. Nothing is steam-bent, so curvy features are bandsawn and go through a multi-step sanding process to reach their final shape. It’s labor-intensive, especially those items requiring hand-tool work. The Dymesichs buy their rough walnut and cherry stock from a local mill, and the two species are still their predominant choice — although hickory, white oak and maple are sometimes used as well.

Running a profitable family woodworking business has definitely generated some insights over the years, and Adrienne shared a few that might be useful for you if you’re contemplating the “craft show” circuit. Adrienne suggests making things with practical purpose, but looking for ways to set your products apart from the crowd with distinctive features.”We’ve also found that people at craft shows want to buy lots of stuff, so items priced at around $20 or so appeal to that shopping mentality as well as to the impulse buyers.” Handmade, utilitarian products sell best directly to customers instead of over the web. “I keep a pan of beans in the booth and encourage people to pick up a spatula and stir them…you’ve got to get things into customers’ hands and work at each and every sale. Sitting in a chair and looking bored won’t do it.” Having a multi-pronged sales approach also helps; juried art fairs are profitable venues, in addition to craft shows and the web. But, try not to travel too far to reach every show, because “the further we have to go, the more competition we face and the less we tend to make.”

So far, the proprietors of Carved for the Cook are pleased with their successes, even though it can be challenging to find time to get it all done. The Dymesichs enjoy the satisfaction of making quality kitchen products, getting out to the shows to talk with customers and generally doing things on their own terms.

“That, and bringing home carloads of money!” Isac jokes.