Some of the hardest-learned lessons involve opening your wallet to fix the mistake. But for John Meyer, costly mis-cuts on a stack of tongue-and-groove cedar proved to be the “eureka” moment that inspired him to develop Correct Cut. It’s a portable miter saw stand with a touchscreen computer that takes manual measuring and marking out of the cutting process.

Meyer was preparing siding for a pair of garage doors he was installing on a house his construction company was building. Six cuts into the process, and without his knowledge, the stop on the miter saw stand shifted 3/8 in., which made all the remaining cuts too short. The mistake cost Meyer another trip to the lumberyard, time lost and $400 for replacement boards.

“After a few choice words,” Meyer recalls, “I knew that there had to be a better way. If there had been a simple display on the stand I would have seen that the stop had moved.”

At the time, a “smarter” portable miter saw stand didn’t exist, but John knew that a better solution would “have to be something more elegant than a stand with a tape measure nailed down to it.” He speculated that it would require a user-friendly computer with a reliable stop system that wouldn’t be affected by the demands of jobsite portability.

That initial spark of innovation happened more than three years ago. Now, after numerous prototypes, design and production challenges, field testing and a significant outlay of John’s finances to fund the project, Correct Cut has become a reality. Meyer began shipping purchased units last month.

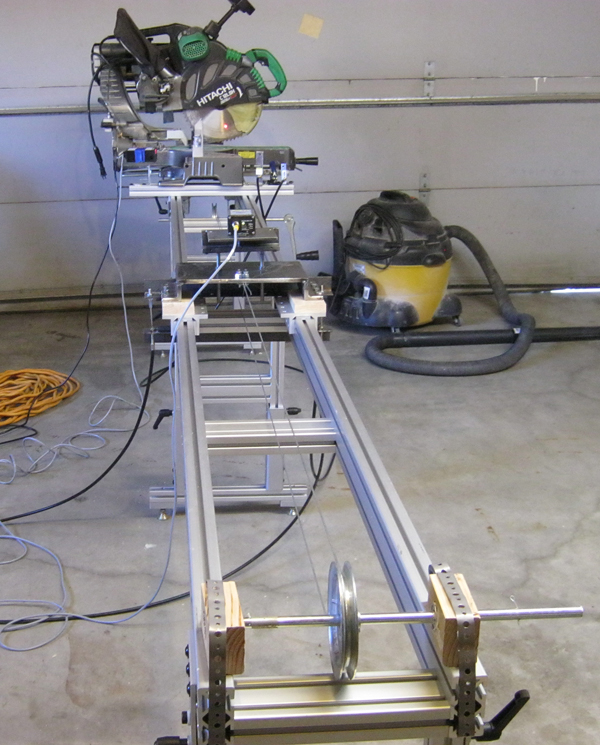

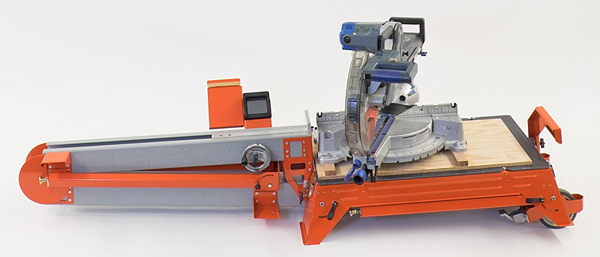

Its styling has remained true to John’s initial vision. The steel stand features fold-out aluminum legs and a long fiberglass side support arm that also folds in half for transport. A crank-driven work stop rides along this arm, and it’s tethered to a touchscreen computer that “knows” its position along the arm, regardless of the model of miter saw being used. A quick calibration process, using six test cuts, allows the computer to set itself to virtually any miter saw the operator installs on it and to determine its level of cutting precision. Correct Cut offers crosscutting capacity of between 10 and 11 feet, depending on the saw, to an accuracy of +/- 1/32-in. Boards up to 16 ft. long can also be cut, using a provided long stop attachment, and an adjustable 4-ft. support on the right side of the stand keeps offcuts controlled.

A pair of wheels with brakes enables easier portability. The 78-lb. unit folds to about 78-in. long for transport, and it can stand vertically against a wall.

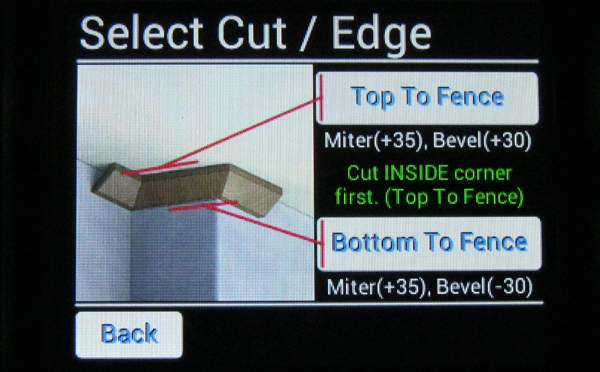

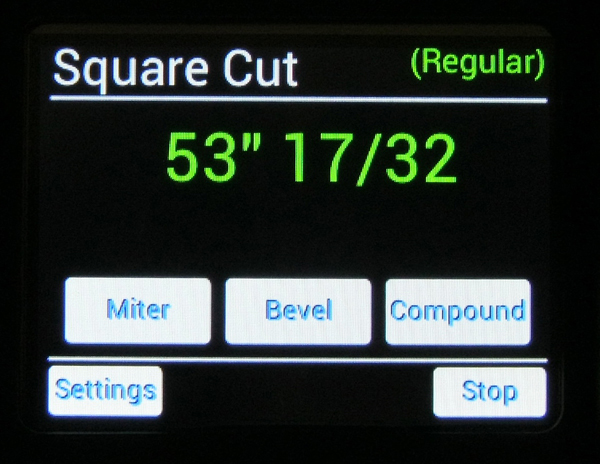

Correct Cut’s touchscreen display, of course, is the product’s standout feature. Once calibrated, it enables square crosscutting, miter and bevel cuts, plus the ability to cut crown molding. It does this through a step-by-step interface that allows the user to choose the type of cut to be made, direction of the cut, any set angles of the molding and the thickness and width of the material being cut. The computer then calculates the length of the workpiece and reports back other relevant information for setting the saw, cutting angle and orientation accurately.

For cutting “sprung” crown molding, probably the most complex compound miter cuts an installer must make, the touchscreen also simplifies the process. It shows a visual representation of how the molding appears on a wall, in order to prompt the operator with saw settings and orientation of the molding. Then, the computer enables moldings to be cut flat on the saw table — the easiest and most accurate method.

“[The touchscreen] helps an operator make square cuts quickly and accurately, make miter and bevel cuts regardless of whether the operator knows the long- or short-point measurements, and it allows the less-experienced to cut crown molding efficiently. It does all this without the need to measure each individual board with your tape,” Meyer reports.

But inventing a smarter solution for miter saws hasn’t been easy. Even Meyer’s seven years as a project engineer didn’t fully prepare him for the ups and downs that would come with inventing and developing Correct Cut. There were numerous challenges along the way.

“Starting with prototyping, I was not anticipating making so many iterations.” It took six tries to get it right.

Developing a “proof of concept” machine — a necessary step in the patenting process — involved working with several machine shops, Boise State University and an independent design firm. John also built his own rough mock-ups from wood, aluminum and welded components, plus had to develop a working proficiency in a CAD program to render the design.

John reports that the touchscreen was a major stumbling block in the development process, but it was one he anticipated. His first touchscreen “looked like a large digital clock display with multiple lines and film push buttons like those on many microwave ovens.” It was expensive and complicated to use. That led to an extended search for a better interface with added graphics.

He also did much of his own software programming. “Writing the original equations for the cuts was pretty simple until I got to the crown molding cuts. It took me a while to find a way to accurately cut the crown because there are so many different crown styles, spring angles and so forth that need to be accommodated.”

But, Meyer says it was well worth the effort: the touchscreen is now more user-friendly and icon-driven.

Patenting Correct Cut was a long process, too, John recalls, with many Patent Office exchanges needed to clarify aspects of his design. For would-be inventors, John suggests talking with more than one patent attorney to determine the best course of action. It also helps to do your homework about the patenting process so you can be better informed.

Material sourcing and production also proved to be challenging, in order to find solutions that met John’s design criteria while also staying affordable. It took Meyer three different sheet metal fabricators before he found one “that could hold the tolerances we needed and really believed in the product.”

Even shipping logistics had its surprises.

“I thought it would just be a matter of putting Correct Cut in a box and sending it. However, with Correct Cut being as large as it is, the size constraints, costs and potential shippers were all issues we had to work through.”

And, if Meyer were to do it all over again, he says he’d consider a crowdfunding source such as Kickstarter, rather than backing the entire investment himself. But, without an outside funding source for Correct Cut, Meyer believes there are virtues.

“I would not be comfortable losing someone else’s money if a project fails. And, having your own money invested is a great motivation to get the product right and get it to market.”

And that is exactly what this inventor feels he now has done with the new Correct Cut miter saw stand — gotten it right and ready for woodworkers’ shops and contractor jobsites.

In hindsight, the process for bringing Correct Cut to market has been “a roller coaster ride with many ups and downs,” but John says that’s a common experience he’s heard from other inventors. And it’s a realistic prospect he’d like to share with anyone setting out to create a new tool or accessory.

“There will be no shortage of challenges, but that’s part of what makes the product development process interesting … If you have a great idea and a passion for it, pursue it. Failing may not be fun, but it sure beats never having tried!”

Learn more about Correct Cut by clicking here.